The Arcata School District was created in 1871, just six years prior to Charles enrolling in the fledgling school district. The photo at the right is a class photo taken in front of the Arcata School circa 1897, more than a decade after Charles graduated. It is unknown whether the building shown had been built at Charles attended. Photos via the Humboldt Historian.

###

Introduction by Janet A. Hopkins:

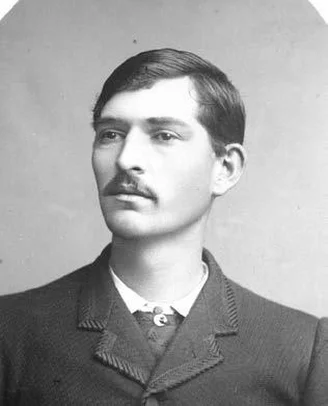

Charles Blodgett Hopkins came to Arcata in the fall of 1877 from Linn, Osage, Missouri. He was the twelve-year-old son of George W. and Elizabeth Dillon Hopkins. His father, a local attorney and a former captain in the Union Army, was in the grips of alcohol addiction which caused the family great hardships. He and his brothers and sister had been both home-schooled and attended a rural school in Missouri. His account was written in 1946.

###

In the fall of 1878, I started the intermediate grade school and got along well, though getting acquainted with the new environment, teacher and pupils was difficult as I had never been a good mixer. I think our economic situation had something to do with my drawback on getting a foothold on myself. However, I made fairly good marks in school for a beginner in a new school.

My second teacher, my first in California, was an old maid by the name of Miss Quick (see Endnote #1). Everybody, young and old, far and near, in this community had gone to school to Miss Quick. Some liked her and some did not. I didn’t stay in her room very long and was promoted to a higher grade in the same building. The new teacher was my third, and his name was Jim Ellis. I don’t remember much about him, only that he was not very sociable with his students and we did not hang around him much. He liked to show his authority. I passed out of this grade with as good marks as the average student. I was in his class about one year and then was sent up to the higher-grade school where there were three grades or classes, A, B, and C. This must have been in the fall term of 1879.

I struggled along for the next two or three years, trying to get the texts we were studying fixed in my mind, but many times they were a complete mystery. Whether it was the fault of the teacher or was I just dumb, I don’t know. I often caught myself listening to the A Class reciting, and it was seldom I could get things straight. Just beyond, there seemed to be a mist through which I must see the answer. The figures they put on the blackboard were a complete mystery to me. At the same time, I knew I was going to learn something about all this. Grammar was another hard subject for me to understand, and still is.

By 1878, we were living in a little shack just across the street and south of where the Arcata High School now stands. Our family was anything but a happy one. Our father was almost continually under the influence of the Demon Alcohol. My oldest brother, Henry Clay “Hal” Hopkins, under the same influence, had left home to seek his fortune among strangers. He lived in Shasta County for many years, working as a miner. My other brother, Walt, three years my senior and my lifelong chum, remained home and found work where ever he could. His education was limited and in consequence he earned what money he got the hard way. As I look back now, I think the conditions at home caused him to seek associates that were none too good for his future welfare.

Our home life was near the breaking point. I can see my sainted mother now sitting there, her hands folded in her lap, the tears streaming down her cheeks, almost ready to give up. She drew me to her side and asked me to promise her I would never bring shame and disgrace to our family using alcohol. On bended knees, my head buried in her lap, I made the promise and I am sure God has helped me to keep that promise.

My next teacher was Mr. William Henry Harrison Heckman ( see Endnote #2). He was a man of wonderful understanding of youngsters of my age and older. At recess and at the noon hour we would all, boys and girls, rather hang around and listen to him tell stories and relate his experiences than go out to the playground. He was a crack shot with a shotgun on the wing, shooting either quail or ducks. He would tell us that it was unsportsmanlike to shoot game of any kind without giving it a chance to get away. We would come back at him with, “A fat chance a quail or duck would have getting away from you if it was flying.” He would laugh all over and smile. Every Monday after he had been on a hunt that Saturday, he would have some thrilling story to tell about his sport that weekend. Mr. Heckman hunted with Mr. Ellis, but Mr. Ellis was neither hunter nor sportsman. He could not hit the broad side of a barn and never had any stories to tell.

Mr. Heckman had more control and decorum in the schoolroom than any other teacher I ever had. I believe I would have learned something if I could have gone to school to him a few years longer. There was never any trouble, I never saw him punish anyone. We knew he meant every word he said, and therefore everyone loved and respected him. Mr. Heckman was a big man, not fat, but well-built, always jolly and in a good humor. He was elected County Clerk of Humboldt County in 1880 or ’82, I’m not sure which it was, and we lost our best teacher.

A man by the name of Mr. J. B. Casterlin succeeded him. Mr. Casterlin was a rather small man, wiry and a pretty good teacher. He was a little impulsive and would lose his temper occasionally and was not as sociable as Mr. Heckman. He stayed only a year and was succeeded by the notorious Mr. Clayborn (#3).

From the very day Mr. Clayborn entered the schoolroom, there was a feud started that increased as the days went by. If a pupil were backward, as there were several, he would be sarcastic and make slighting remarks instead of helping the student. He would say unkind and cutting remarks to them during recitations periods. No one liked him, and I often wondered how he held his job. I went to school to him a year or so, and I guess my parents decided that I was not learning much. I could quit and go to work when I could find it.

In 1882, toward the end of my schooling, an incident occurred that I often think about. Mr. Clayborn was my last teacher, and none of the students liked him. He was always in a scrap with someone. One cold winter morning, we were all huddled about the big stove. To torment Mr. Clayborn as much as we could, someone dropped a piece of Asafetida—everyone was carrying some of this medicine to keep from taking some kind of disease—on the stove, which made an awful stench.

If a bomb had dropped, the crowd of youngsters could not have scattered any quicker. The teacher ran to the lab, got some alcohol and poured it on the stove. In a few minutes the stench cleared. Mr. Clayborn paced the room several times, and then stopped facing all of us (we were all seated by then). “I have a notion to take my coat off and wallop the last one of you!” at which all the students started laughing. The teacher was so mad he could not speak for a minute or so but kept pulling on his two-inch long mustache. Finally, he decided to drop the matter for the time being and went back to his desk and called the first class.

When Mr. Clayborn would come out on the porch to ring the bell for one o’clock, the boys would start on a game of chase called “Follow the Leader.” The girls would go up the street to a platform and sit down until the boys would come back. Then the whole group would straggle into school one after the other, sometimes taking five or ten minutes for all to get seated. These were happy days even if we were willful and naughty kids.

Another day, a chum of mine and I cut school on a Friday afternoon to go fishing off the wharf. Clayborn lived in Eureka and always went home on Friday afternoons. Lo and behold, a car drove up to meet the boat and there sat Mr. Clayborn in the front seat looking directly at us. We pretended to be pulling fish out until the car passed. Next Monday morning, he called us up to his desk immediately after school was called and asked us why we were absent on Friday. We told him we had permission from our parents to go fishing. He came back at us with a scowl, saying, “Yes, I saw you and it is well you had permission, or I would settle with you.”

Not long after that, the most exciting incident of all occurred. Johnny Woods, a wiry little fellow and one that would fight a buzz saw, got into trouble. Clayborn was going to trim him, but when Clayborn got up and started for Johnny, he turned and started for the back of the school room with Clayborn after him and round they went.

There was a half-open window, and when Johnny came ‘round to it he cut out like a sparrow and around the building to the front where Clayborn met him. Johnny took to the street. It was raining and there were puddles in the street, and down that wet street they went, Johnny taking the middle of the puddles like a jack rabbit and Clayborn coming in second. Johnny left Clayborn so far behind that he gave up the chase and came back, mud from head to foot. Such is the life in a country school!

During the last two years of my school days, I had a few close friends. Among them were my two cousins, Mattie and Davis Dillon (#4) who I had known (though not intimately) for years; George Richards; Harry W. Jackson (#5), Emily and Minnie Galinger (#6), Charlie Stouder (#7), Jessie and Millie Armstrong (#8) and their mother, Aunt Inez. She was always like a mother to me right up to the last time I saw her in 1924.

The one friend that stands out more clearly than the others is Harry W. Jackson. He was an “A” grader, exceptionally bright, a good sport, sociable and had a good head on his shoulders. Our first close association came about like this: It was a damp, rainy day in December. At morning recess, most of the boys had gotten into a game of throwing mud. It was a dirty kind of play and the teacher called in all those who were involved in the mudslinging, me included, and gave us a moral as well as humiliating lecture. We were given the penalty of two weeks confinement, at recess, in a lot about 40 x 100 feet near the rear of the building. We were not long in adjusting ourselves and chose Harry as the captain of the Mud Brigade. This incident linked our lives together in such a way that there was a mutual understanding between the two of us for year to come.

After I left school, I often wished I might plan some way that I could go to college. In those days the opportunities to work your way through college were slim. If you did not have the means to pay the major part of the expenses, it was just too bad for you. My parents were not financially able to help me much. After a man was past 21 years of age, there were few that could go through college without some help from relatives or friends unless there had been some provision previously made for that purpose.

In 1904, I took a course in architectural drawing and design from the International Correspondence Schools when I first went into carpentry. The mathematical part of which was a wonderful help to me in later years. At the time I was taking the course, I was working hard every day at the carpenter work and doing all my studying and drawing at night which was bad on my eyes. As a result, I had to stop most of the night work and eventually the course was neglected.

I was always fond of music and tried to learn on several instruments but finding time to practice kept me from accomplishing much. My great desire as a young man was to create something that I could see after the work was completed. A railroad work came nearer to this ideal than any other work I had ever followed. I was never forward or aggressive in company, a good listener and always tried to see both sides if there was any argument. I have had the responsibility of overseeing and directing the work of other men and always found it the best policy to be gentlemanly and courteous to those under me.

###

Note from Janet A. Hopkins:

In later years, Charlie mortgaged the family home and sold landholdings in the Ukiah area to put his sons through college. They both went on to have successful professional careers.

Eldest son C. Howard Hopkins, PhD, wrote numerous books including A History of the YMCA, John R. Mott: A Biography and The Social Gospel. He was emeritus Professor of History at Rider College, and also taught at Stockton Junior College and Bangor Theological Seminary. He later was the Dean of Stetson College in Florida.

Charlie’s younger son, Cleveland Hopkins, graduated from Stanford University and worked for the government for most of his career, beginning at MIT and the early development of the radar through his work on the Early Warning System during WW II. He was present at the early tests of the atomic bombs that were used on the Japanese. His subsequent work focused on various peace time efforts by the US government.

###

ENDNOTES

1. Miss Elizabeth “Eliza” Quick was living in Ferndale in 1880, her occupation was teacher. Twenty years later, she was living in Bucksport, still single and still teaching. Eliza was born November of 1859. It is interesting that Charlie called her an “old maid” at only 20!

2. William Heckman appears in the 1900 census married to Mary C. Heckman. They were living in Eureka Ward 3. William was born August 1850 in Pennsylvania.

3. I believe this may have been William Frank Clyborne from Michigan. He was 24 and a teacher in the 1880 Census. Later census records noted that he became an attorney and married Jane “Jennie” V. Gage in 1881.

4. Children of John Randolph and Mary Ann Tracey Dillon.

5. This is likely Harry Woodville Jackson, son of Elisha and Corelia Kendall Jackson of Martins Ferry. The family went to California from Aroostook County, Maine in 1873. Harry was born in Abbot, Maine January 1863. He married Alicia May Betancue in April 1890.

6. Emeline Esther and Minnie Galinger were the daughters of Abram and Zetta Galinger who emigrated from Bavaria in 1870. The girls were born in California. In 1880, the family is living in Arcata.

7. Charlie was the son of Frederick and Margaret Haroner Stouder. His parents were Swiss and had initially emigrated to Illinois in the early 1850s before going on to Arcata in the 1870s. Charlie married Mary Dodge and later moved to Oregon.

8. I suspect this is likely Mary Jane “Jessie” and Minnie Pinkerton, daughters of James and Margaret Mitchell Pinkerton of St. Patrick, Charlotte, New Brunswick, Canada. Jessie married Edward J. Armstrong in 1883. An older brother, Harvey, arrived in Eureka in 1881, as did Jessie.

###

The story above was originally printed in the Fall 2019 issue of The Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society, and is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE