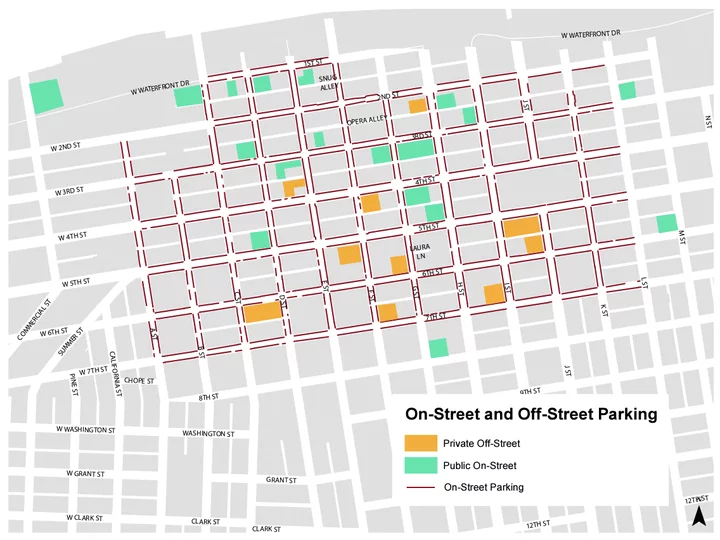

Map of Eureka’s on- and off-street parking taken from a recent Old Town and downtown parking study commissioned by the City of Eureka.

# # #

Rob Arkley’s recent tirades directed at Eureka city staff and elected officials were shocking for their insulting and bullying tone, their profanity and the blatant sense of entitlement to special treatment that they reflected.

What was not so shocking was Arkley’s underlying premise: the idea that “parking is the lifeblood of downtown retail and restaurants” and should be prioritized over all else, including affordable homes. This assumption is so common as to be unremarkable. But that doesn’t mean it’s true.

Research in the United Kingdom has shown that while access to parking may be important to retailers in low-density suburban environments, it is not the amenity many assume for a downtown. The studies show that downtown business owners severely overestimate the proportion of their customers who arrive by car; that people who walk, bike or take the bus spend more at local businesses over time; and that abundant free parking can actually hurt business by lowering turnover and getting in the way of what shoppers actually want — an inviting atmosphere and diverse retail mix.

The actual “lifeblood” of downtown businesses is not parking - it’s customers. Given that people who walk, bike or take the bus end up spending more, it’s pretty clear that putting a lot more people within walking and biking distance of shops, and improving public transit, is a much better bet than abundant free parking.

In this context, it’s confounding that business owners like Arkley have put up such a stink about replacing underutilized parking lots with downtown housing and a transit center. (A plan to build a much-needed transit hub in Crescent City has even drawn concern over loss of parking from non-profit community institutions like the library and community foundation, despite those institutions’ clients being even more likely not to drive.)

This resistance to losing some parking spaces is even more notable because, as the Outpost has reported, independent third-party analysis has shown that downtown Eureka has more parking than it needs, and much of it goes largely unused.

It’s also well documented that providing a lot of parking, far from being just a natural response to high driving levels, actually causes people to drive more, thereby increasing congestion, traffic deaths and injuries, and pollution. The passionate defense of parking by Arkley and others, however, seems immune to facts like these.

A recent study, also from the UK, has put a name to this phenomenon: “motonormativity,” which the researchers define as “unconscious biases due to cultural assumptions about the role of private cars.” These researchers surveyed a cross-section of the British public and found that people hold deep-seated opinions about cars and driving that cause them to suspend the ethical and moral judgements that they would apply in other contexts.

For example, people overwhelmingly disapproved of exposing others to second-hand cigarette fumes by smoking in populated areas, but endorsed exposing people to second-hand exhaust fumes by driving in those same places.

Another example of this pervasive motonormativity shows up in Arkley’s professed concern over the safety of his female employees having to walk a few blocks to work. Statistically, it is far more likely that a person will be injured or killed in a car crash than from assault on the street. But Arkley apparently shares the feelings of those surveyed in the British study, who felt that risk of injury is an acceptable characteristic of driving but not of any other kind of work.

You may notice that a lot of this research has been conducted in Britain and not the United States. Before dismissing the results with an appeal to American exceptionalism, consider that car culture is even more entrenched here than across the pond — so entrenched, in fact, that few if any researchers are even questioning it here, as they are in the UK. It’s highly unlikely that research in the U.S. would find people — and business owners — any less motonormative than their British counterparts.

This bias has real impacts. Motonormativity leads to Americans responding to 40,000 car crash deaths and over 50,000 deaths caused by tailpipe emissions every year with a collective shrug. It leads to climate-conscious citizens and politicians remaining largely silent on our single biggest source of climate pollution. And of course it leads to business owners regularly advocating against projects and policies that are in their own best interests.

Vehicles are machines, tools that can be used many different ways — or not at all. But they are also layered with a lot of emotional baggage. Today’s transportation issues are as much or more about culture as they are about technology.

It’s time to acknowledge that, and to openly question the internalized motonormativity that leads us to counter-productive, knee-jerk reactions like Arkley’s whenever a parking spot or driving lane might be modified or removed. Successfully challenging these deep-seated biases is a key first step toward improving our safety, our health, our climate — and our businesses’ bottom lines.

# # #

Colin Fiske is the executive director of the Coalition for Responsible Transportation Priorities.

CLICK TO MANAGE