Jestine Green (right) pictured with her friend Debra Thomas. Photo: Debra Thomas.

###

On a cold January night shortly after the new year, Jestine Green climbed into a commercial recycling dumpster to take shelter from a relentless winter storm. The following day, her body was found among the recycling that had been taken to the Samoa Resource Recovery Center by a Recology truck.

In the weeks following Jestine’s tragic death, homeless rights advocates have called upon local officials to take immediate action to prevent such a tragedy from happening again. From providing more support to those in need to challenging the criminalization of homelessness, there are no easy answers.

The truth, as it often does, lies in a complicated web of systemic issues that have plagued our society for far too long. Jestine’s death was not the result of any one person’s actions or inactions, but rather a series of unfortunate incidents and factors that contributed to this terrible accident.

A History of Mental Illness and Addiction

Jestine Green was born on August 17, 1965. Her parents, Lydia and Mel Green, raised Jestine and her two siblings, Stefanie and Syd, in the small community of Whitethorn among the forested hills of rural Southern Humboldt.

As a child, Jestine enjoyed art and exploring nature with her mother. “[We] had fun drawing together, she was a great artist,” Lydia Green wrote in one of a series of emails with the Outpost. “We loved the ocean and playing in the tidepools together.”

Her mother described Jestine’s upbringing as “normal,” emphasizing that she and her siblings grew up in a Christian household where alcohol and drug use were not tolerated.

“Her boyfriend introduced her to drugs when she was 15,” Green said. “Jestine did not like rules and she found it hard to live with us [because] there were no drugs or drinking at our house. … She was a victim of being beaten by her boyfriends [but] we were told [it was] her business, her life. We put her in rehab three times [but it] did not help. … Jestine lived the life she wanted and that did not include the family … but when she was clean, she was the sweet Jestine we all remembered.”

Jestine struggled with mental illness throughout her life, which her mother largely attributed to the “effects of drug use over time” and the abusive relationships Jestine endured.

Her siblings, Syd and Stefanie, struggled with addiction and mental illness as well. Syd committed suicide about 30 years ago after spending some time at the Crestwood Behavioral Health Center for drug abuse, Green said. Stefanie is homeless and hasn’t been in touch with her family for the last three years.

Jestine had an apartment in Eureka “for a short period of time,” Green said, but it fell through and, eventually, she wound up on the streets. “We had no way of getting ahold of Jestine unless we drove along the streets of Redway or Eureka. Sometimes we would see her walking along the road or freeway, pick her up and bring her home. … I would come home from work and she would be gone. [She would] always [leave] a note saying thank you.”

As a young woman, Jestine gave birth to five children who were fostered out to other families, her mother continued. They never really developed a relationship with Jestine, and neither did her six grandchildren. “I don’t believe she ever met any of her grandchildren,” she said.

Green didn’t have a lot to say about Jestine’s adult years, as she was estranged from their family for decades. Her responses to this reporter’s questions focused on Jestine’s addiction issues and her inability to raise her own children. She maintained that “Jestine was homeless because she wanted to live in homeless camps [because] they were her family and friends.”

Debra Thomas, a homeless rights advocate and co-founder of Affordable Homeless Housing Alternatives (AHHA), argued that anyone who claims someone wants to be homeless “clearly hasn’t spent a one night on the streets.”

Thomas met Jestine about ten years ago while doing homeless outreach work in Southern Humboldt. She recalled Jestine’s “sweet smile” and described her as “an incredibly kind and gentle person.” Over the years, she developed a friendship with Jestine, who often referred to Thomas as her sister.

Jestine Green (left) and Debra Thomas. Photo contributed by Debra Thomas.

“I met her many, many years ago when she was still housed, and then I started to help her when she was unhoused,” Thomas told the Outpost during a recent phone interview. “I never knew a whole lot about her personal life with her family, but she always used my phone to call home. I know she loved her family and that she wanted to go home.”

But at a certain point, Thomas believes Jestine’s mental health issues became too much for her family to handle and they stopped taking her calls.

“I really did watch her spiral over the years as she struggled with mental health issues and the abuse she experienced,” she said. “Living on the streets only compounded her trauma. There was a time when she actually was able to get medical help through the Mobile Medical Unit and I believe she was put on medication because, for a while, she was herself again. It was really life-changing. She was like that for a while but apparently fell off at some point.”

Thomas paused as she spoke and took a deep breath. “This is what happens when you create so many barriers for people,” she said. When cities and institutions deprive people of solutions, it creates unsurpassable barriers for people struggling to survive, she explained. “And when you create these barriers, you essentially criminalize human beings for existing.”

“Jestine was criminalized and pushed out of town by vigilantes [in Southern Humboldt] because she was homeless,” she said. “She was picked up for being drunk in public, taken to the jail in Eureka and released hours later. This happened over and over. For the first couple of years, she could make it back. I, or someone else she knew, would bring her back, but she eventually got stuck [in Eureka].”

‘I Just Wish She Would Have Come Back’

Kristin Freeman, director of the women’s shelter at the Eureka Rescue Mission, described Jestine as “a frequent flier” at the shelter. “She would come and go – sometimes for weeks at a time – but she knew she was always welcome.”

Freeman grew concerned when Jestine didn’t return to the shelter on the night of Jan. 4.

“Jestine came in for shelter [at the Rescue Mission] for a few nights before and we kept her bed for her,” Freeman told the Outpost in a recent phone interview. “Her bed was still made up, her things were still there. … When she didn’t return the following morning, we stripped down her bed and gave it to another person.”

The greater Eureka area received over an inch of rain that night. Freeman thinks Jestine was “on the other side of town” when the storm hit and decided to seek temporary shelter to wait out the weather. Her body was found the following morning.

Freeman was devastated when she heard what happened.

“There was room for her at the shelter,” Freeman said, her voice quavering with emotion. “She knew she had a bed there, you know? I just wish she would have come back. … She was such a sweet soul. I don’t think she had an aggressive bone in her body. It didn’t matter where she was at in her life, she was always so respectful and kind. It really hurts to lose one of yours.”

An autopsy ruled Green’s death to be accidental with “no suspicion of foul play,” according to the Eureka Police Department. The toxicology report ruled out the possibility of an alcohol or drug overdose, although there were trace amounts of methamphetamine, amphetamine and THC found in her blood.

Her official cause of death was deemed “consistent with mechanical-traumatic asphyxia, due to external pressure-compression of the [chest and abdomen],” according to the autopsy report. “[She had] been situated within a dumpster and had previously taken refuge there during a storm. The dumpster contents were subsequently picked up and transferred to the recycling truck and compressed during the course of its route. The recycling vehicle emptied its contents … and [Jestine’s] body was discovered at that time.”

It was an accident. A terrible, terrible accident.

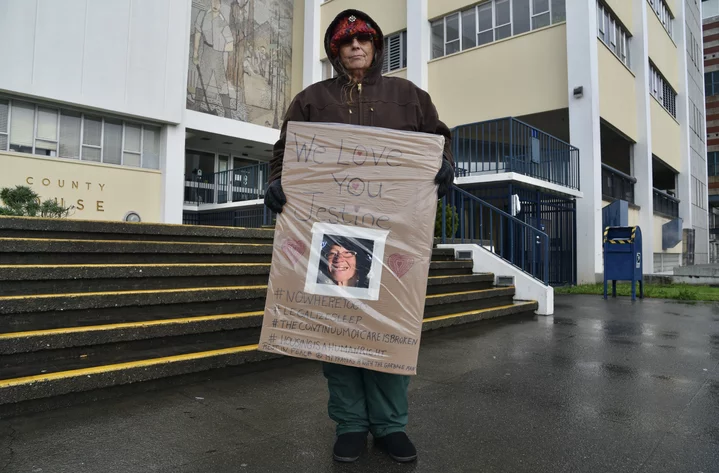

Debra Thomas holds a cardboard sign displaying a picture of Jestine Green at a recent demonstration at the Humboldt County Courthouse. | Photo: Isabella Vanderheiden

‘We Can Do Better’

A small group of community members gathered in front of the Humboldt County Courthouse on a stormy Saturday afternoon about a week after Jestine’s death to honor her life and call upon local officials to do more to care for people experiencing homelessness in our community.

“I don’t want this to ever happen again to anybody,” Thomas told the Outpost during the Jan. 9 demonstration. Her gloved fingers held a cardboard sign adorned with red hearts and the words “We Love You Jestine” surrounding her photo. “Our whole community loses when these kinds of tragedies happen and I really think we can do better. We should always be trying to improve the situation for human beings that are stuck outside, and I just think we could have done more to prevent this tragedy. People need to have a place to go.”

Of the 1,309 unhoused people identified during the 2022 Point in Time (PIT) Count, 756 individuals were identified as “chronically homeless,” meaning they’ve been unsheltered for at least a year while living with a complicating health issue or have experienced multiple bouts of homelessness totaling at least 12 months on the streets and in shelters in the past three years.

Of the 756 people identified as chronically homeless, only 20 percent – approximately 151 individuals – are consistently sheltered. Where do the remaining 605 people go?

The PIT Count did not include that data; however, of the 250 individuals surveyed as a part of the Eureka Police Department’s Homeless Survey for 2022, only 28 percent of respondents said they slept at a shelter the night prior. Around 50 percent of those surveyed slept outside in a doorway or alleyway, in a park or greenbelt, on private property or in a vehicle.

“The City of Eureka and the county need to consider more housing alternatives,” Thomas said. “We know we don’t have enough housing. We don’t even have enough shelter beds. We need to consider the possibility of making places for people to exist outdoors because people can live outside if they have proper gear and the supplies they need. We need to have a place established – whether that’s a tiny house village of sorts or a sanctioned camping area – prior to these storms hitting so people can prepare for their safety.”

The City of Eureka has been looking into the possibility of establishing a tiny house village for some time now. Eureka City Manager Miles Slattery emphasized the city’s commitment to trying out innovative strategies.

“Jestine’s death was extremely tragic,” Slattery told the Outpost in a recent interview. “It has been really difficult for everybody involved and we’re going to do anything that we can to prevent this from happening again.”

How do we house Humboldt’s homeless?

Homelessness is not an issue that can be solved with a one-size-fits-all approach. The factors that cause homelessness are complex. Mental illness, substance abuse and physical disabilities often play a role, as does access to supportive services and treatment.

Emi Botzler-Rodgers, Behavioral Health director for the Humboldt County Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), emphasized the importance of “meeting people where they are” and committing “a significant amount of time to build a relationship and establish safety and trust” with an individual.

“There are frequently robust efforts by county staff to outreach to these individuals and to create space to build trust and rapport so they are willing to engage in treatment,” she wrote in an email to the Outpost. “However, despite these efforts, individuals in need of mental health treatment still have the choice to receive these services or not. This can be especially challenging for those closest to the individual suffering.”

In most instances, the county cannot force an individual into treatment.

“One exception is if they are a danger to themselves, someone else or aren’t able to adequately provide for themselves (gravely disabled) due to mental illness,” she said. “However, this doesn’t ensure they will continue to receive ongoing treatment after the crisis is over. This can feel very frustrating to friends and families, [our] staff and the community.”

The Humboldt County Board of Supervisors launches a Laura’s Law pilot program last summer which allows for court-ordered assisted outpatient treatment. While there are no legal ramifications to an individual refusing to participate, involving the courts and a judge often makes it more likely for individuals to comply with assisted treatment.

Last year, the City of Eureka added a managing mental health clinician position to serve on the police department’s budding Alternative Response Team (ART) and bolster the City’s response to mental health crises.

ART will work in tandem with the department’s Community Safety Engagement Team (CSET) to further CSET’s mission to address substance abuse and crime within the homeless community.

“One of the greatest challenges we have with our local homeless population is, at times, they’re not always willing to accept help,” Leonard La France, commander of CSET, told the Outpost. “How do we help people who don’t want to or are unable to help themselves? That’s the question we constantly ask ourselves as we work within this system and try to fix the system.”

Similar to Botzler-Rodgers, La France believes one of the most important aspects of addressing homelessness is daily engagement and treating people with compassion.

“Our philosophy is human connection,” he said. “You know, we see people like Jestine every day and they’re kind of like extended family, especially to our outreach workers. Sometimes it takes three years to build that connection, but we don’t give up. Like, ‘We see you. We care about you. Let’s get this going to get you moving forward on a better life where you’re not in danger, you’re not at risk, and you’re warm.’ If we can assist these folks in getting stabilized, getting assistance and the support they need, it’s better for everybody. It’s better for the community.”

Although the Housing First model is widely regarded as the best practice for addressing homelessness, La France admitted that “it doesn’t always work for everybody.”

“We have to help get an individual stabilized, address their personal needs, help them find employment and then start looking at the next step,” he said. “For example, we had an individual we worked with closely – we received more than one hundred calls on him per year – and our team talked to him and he said, ‘I want to go back home to my family in Missouri.’ We contacted his family to confirm he had a place to go and that his family would receive him and we were able to send him home.”

One of CSET’s non-sworn employees talks to him almost every day, La France added. “He’s employed, with his family, and he’s doing really, really well.”

Working alongside UPLIFT Eureka, the CSET team has helped house over 150 people in the last year and a half through Uplift’s housing assistance program, according to Slattery.

“On top of that, we continue to work with Betty Chinn on the Crowley Site,” he added, referring to a city-owned lot on Hilfiker Lane, near the Hikshari Trail and between the Humboldt Bay Fire Training Facility and the Elk River Wastewater Treatment Plant. PG&E donated a batch of trailers to the Betty Kwan Chinn Foundation over five years ago to be converted into housing. However, the trailers were destroyed in a fire last year. “[The city] has secured a $1.6 million grant to put utilities on the property and allow for [the project] to happen.”

In an effort to address immediate shelter needs, the city has helped the Eureka Rescue Mission expand shelter capacity in both the men’s and women’s shelters in recent months. The city has also changed its extreme weather shelter to an overflow shelter with 25 extra beds.

Eureka has also worked to develop a city-specific Homeless Action Plan to expand efforts to address mental health and housing needs in Eureka. The document outlines the city’s ongoing efforts to reduce homelessness in the city by expanding affordable housing, bolstering outreach efforts and expanding partnerships with organizations that provide services to people experiencing homelessness.

“We have spent millions of dollars over the past three years to implement supportive programming and services in Eureka, with help from [DHHS],” Slattery said. “It’s really unheard of what the City of Eureka has done.”

The city will host a workshop this week to broaden the conversation and explore the requirements necessary to establish an authorized encampment. The workshop will include presentations about the conditions of approval outlined in both the city and the county’s emergency shelter ordinances and the steps required to create a shelter space for community members with tent structures or tiny homes.

“The idea is to give people the information they need to create their own authorized encampments,” Slattery said. “We’re hoping people will be encouraged to come up with a game plan that can be successful … and put it in a format that can be presented to the council and ensure that some of the issues council has seen before can be mitigated. Once [the plan] is approved by the council, they can find a location.”

The authorized encampment and tiny house workshop will be held at 5:30 p.m. on Tuesday, Feb. 28 in council chambers at Eureka City Hall – 531 K Street.

‘We need to have alternatives for people’

It bears repeating that there is no single solution to the homelessness crisis. While Thomas believes that the aforementioned initiatives are a step in the right direction, many advocates say more needs to be done to address the root causes of homelessness and provide long-term solutions to this complex issue.

“I just keep asking myself why Jestine jumped in that dumpster and I feel like it’s because she didn’t have an alternative,” Thomas said. “We need to have alternatives for people. … I appreciate what the City of Eureka is doing but we need the continuum of care to spread out – not just in Eureka but across the entire county. … If we can get this group of people in a safe place, our entire community will be safer.”

CLICK TO MANAGE