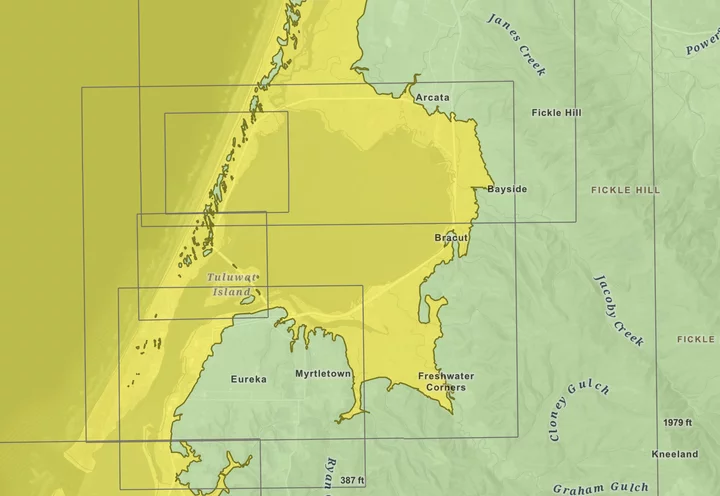

Do you know your zone? | Screenshot of the Tsunami Hazard Area Map.

###

When a 7.0 magnitude earthquake struck the North Coast on Thursday morning, staff at the National Tsunami Warning Center (NTWC) in Alaska sprang into action, promptly issuing a tsunami warning for an estimated 5.3 million people in coastal communities across Northern California and southern Oregon. Hundreds – perhaps thousands – of Humboldt County residents fled their homes and offices in a chaotic search for higher ground, which led to gridlocked traffic on Highway 101 in Eureka.

After assessing tsunami forecast models and water levels from offshore buoys for about an hour, the NTWC determined that there was no threat of a tsunami on the West Coast and the warning was canceled at 11:55 a.m.

Humboldt County hasn’t experienced an earthquake of this magnitude since April 25, 1992, when a series of magnitude 7.2, 6.6 and 6.5 earthquakes struck the Cape of Mendocino, destroying dozens of homes in the Mattole and Eel River valleys. However, the magnitude of an earthquake clearly doesn’t always mean it’s more destructive. The 6.4 earthquake that occurred on Dec. 20, 2022, caused far more structural damage than yesterday’s quake, even though it was of a notably smaller magnitude.

[CLARIFICATION: As one of our readers points out in the comment section below, in June 2005, a magnitude 7.0 earthquake struck 80 miles west of Crescent City, prompting evacuations in low-lying areas. However, there were no reports of serious damage.]

In the hours that followed yesterday’s earthquake, some locals took to Facebook and other social media platforms to accuse the National Weather Service, public safety agencies and local media organizations of fear-mongering and blowing the whole thing out of proportion.

“I was born and raised here,” one person wrote in our Facebook comment section. “I knew that quake was not strong enough to cause a tsunami large enough to cause mass hysteria and panic.”

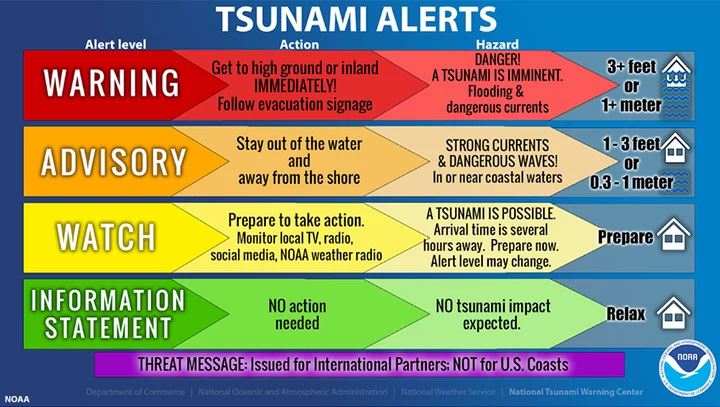

Ryan Aylward, a warning coordination meteorologist with the National Weather Service (NWS) office in Eureka, disputed the notion that the earthquake wasn’t “strong enough” to cause a tsunami, adding that the Tsunami Warning Center typically issues a tsunami warning following coastal earthquakes of magnitude 6.5 7.0 or greater.

“There was no doubt from anyone here that that earthquake was big enough to cause a tsunami. It wasn’t even a question,” Aylward told the Outpost in a phone interview. “It was a very real threat, and we’re just very thankful that it was a very small tsunami.”

When an earthquake occurs, the good people at the NTWC in Alaska assess the location and magnitude of the earthquake, as well as the region’s history of tsunamis, and decide whether an alert should be issued.

Image: National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration.

“We have the Cascadia [subduction zone] right off our coast, and we know that in 1992 an earthquake produced a tsunami at the cape there that was three feet,” Aylward said. “In this case, the first indication was that it was a magnitude 7.3 in about the same spot as 1992. So, in those first five minutes, they had to make a decision, and they made the decision to issue a warning because they felt a tsunami could be generated.”

After the tsunami warning was issued at 10:51 a.m., NTWC and NWS staff monitored wave activity from offshore buoys and tidal gauge stations at the North Spit of Humboldt Bay and up in Crescent City but, fortunately, no unusual activity was detected.

“We did detect a nine-centimeter wave in Point Arena in Mendocino County, but that was small enough that the tsunami warning center decided to cancel the warning about an hour later,” Aylward said. “It takes, you know, 10 to 20 minutes for the waves to arrive, and then you have to wait to see. An hour is about how long it takes to analyze the waves and make a determination.”

The Humboldt County Office of Emergency Services (OES) issued its own tsunami warning about 45 minutes after the national alert. Asked what took so long, Emergency Services Program Manager Ryan Derby told the Outpost that the OES “must contact the appropriate agencies to verify if there is threat of a tsunami before a Humboldt Alert is sent out,” which “can take time.”

Not long after the tsunami warning was lifted, one of ALERTCalifornia’s cameras captured a video, as seen below, of Humboldt Bay appearing to recede, a possible indicator of an incoming tsunami.

“It does look like something happened, but we don’t know what. The folks at the California Geological Survey will be looking into that further, but my first guess is that it’s a seiche,” Aylward said, referring to a standing wave, typically caused by wind, that moves back and forth across a partially or fully enclosed body of water, such as a lake or bay. “We didn’t see anything at the tide gauge … but we really don’t know at this point.”

Asked how he felt about yesterday’s earthquake response, Aylward acknowledged the chaos that ensued on Highway 101 in downtown Eureka and on the Samoa Bridge when traffic was gridlocked and urged people to evacuate on foot.

“Yesterday, we saw lots of people driving and getting stuck in traffic, especially on Samoa Bridge. You don’t want to go through the tsunami zone to get to higher ground,” he said. “Knowing your evacuation route and knowing the closest place to where you live is really important. Someday a big tsunami is going to hit and people need to respond in the correct way and follow their evacuation routes, otherwise, they’ll get stuck in their car in traffic when the waves are arriving.”

And if you’re not in the tsunami zone, don’t evacuate. “If you’re, like, right on the edge of the zone and you’re not feeling comfortable, go ahead,” Aylward added. “But if you’re solidly out of the zone, you don’t have to leave.”

Not sure if your house is located in the tsunami zone? Check out the state’s interactive Tsunami Hazard Area Map – linked here. Additional resources can be found at the Redwood Coast Tsunami Work Group’s website and at ready.gov/earthquakes.

You can also check out this thread on X, formerly known as Twitter, from NWS Bay Area that goes over yesterday’s emergency response.

CLICK TO MANAGE