The USS Harris. Photo: U.S. Navy Bureau of Ships. Public domain.

I was 21, and I was leaving home for the first time, riding the Northwestern Pacific Railroad from

Humboldt County to the Naval Training Center in San Diego; from there, I was to ship out to Pearl

Harbor on December 4, 1941.

###

September 20, 1941: Pop woke me. He wanted to say goodbye before his ride to work arrived. I hadn’t slept much; I was too keyed up. Two weeks earlier, I had enlisted in the Naval Reserve as a carpenter’s mate, third class. I qualified for that rate because I had completed an apprenticeship in the Carpenter’s Union: that meant only three weeks in boot camp, and a starting pay of $60 a month, instead of the $21 a month as an apprentice seaman. The enlistment was for one year. Mom was up. as was my younger brother. Frank, and my sisters, Helen, and Marion. My older brother, Al, drove me to the station. I left with a change of clothes and my Ziess camera. Two and a half years and 200,000 miles of water passed under my feet before I saw my family again.

Mom had packed a lunch for me to eat on the train; there was no dining car on the Northwestern Pacific between Eureka and San Rafael. At the depot, I bought a couple of Cokes. Walter Cave, the conductor and a neighbor of ours, greeted me. There were very few people in the three passenger cars that foggy morning.

I had ridden a train once — a logging train, when I was twelve. Howard Smeds and Varvel Carter and I had hitched a ride to the logging camp southeast of the Cutten Tract where Howard’s aunt worked as a waitress in the cookhouse. We were angling for a free lunch.

We rode our bikes as far as we could up the trail, stashed them, and walked to the clearing that met the railroad where it made a sharp bend on an uphill grade. The train had to slow down at that point and it was easy to catch one of the empty cars.

Howard’s aunt gave us a good lunch. When the train was loaded with logs, we hitched a ride back to our bikes.

Several years later, we made the trip again, only this time, it was a long hike. In the Depression years, the mill had gone into receivership, and the logging camp was abandoned. The rails and cross-ties were removed. The six or seven trestles, some fifty to seventy feet high, were left with two large girders supporting the cross ties and the rails. Without railings, we walked those girders on the trestles high above the stream. Vandals had broken the windows in the camp, but the stove, tables, and benches remained in the cookhouse. Cots and mattresses, torn and littered by pack rats, were the bunkhouse.

December 6, 1941: Aboard the USS Harris, at sea. The weather was better: we’d had a windy night. Topside, the rail was lined with sailors hanging their heads over the rail; to get to the chow line, we had to step over seasick sailors lying on the deck.

My best friend from boot camp. Morry Couch, and I were up on the deck near the fantail, relaxing on a metal still in ready box. I said, “Morry, I’ll be twenty-two tomorrow. Do you think Cookie will bake me a chocolate cake?”

“It’s Sunday,” Morry said. “We’ll probably have cake for dessert.”

December 7, 1941: Morry and I were standing on the deck at 0730. We’d eaten breakfast, and we were watching the sun rise over the white caps ofthe Pacific.

“Happy birthday, Ted,” Morry said. “I bet you’ll never forget this one.”

Suddenly, the PA system crackled and the captain spoke. “… Pearl Harbor has been attacked by the Japanese Air Force…. We are now at war with the Empire of Japan…”

Only a year earlier, a Japanese ship had pulled into Humboldt Bay and taken on a load of scrap iron. Now, I thought, they’re going to shoot it back at me.

December 11, 1941: The USS Harris entered the channel to Pearl Harbor. We lined the rail on both sides, and approached a battleship on the port side. She was hard aground, her hull low in the water. It was the USS Nevada. The USS California was next. Her #l 14-inch gun turret was awash with water lapping at the barrels.

We saw the Oklahoma with half its bottom and keep showing; the West Virginia and Tennessee were burned-out hulks, sitting low in the water. Only the top of the 14- inch #2 gun turret on the Arizona was visible.

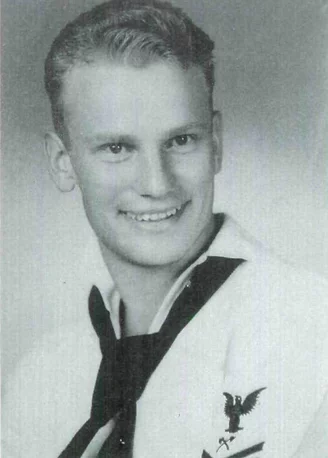

Ted Gruhn, following boot camp in 1941, a carpenter’s male, third class. Photo courtesy of the author. via the Humboldt Historian.

December 23, 1941: My bunkmate, Glen Moody, and I received a message to report to the personnel officer. As we stood at attention, we were told that we had both been assigned to Honolulu Shore Patrol duty, beginning the following Monday.

“Sir.” I said, “I was looking forward to sea duty on a destroyer. Is this a permanent assignment?”

“Yes, Gruhn, this is a permanent assignment for as long as your SP commanding officer wishes it to be.”

“Thank you, sir,” I said, “and a Merry Christmas to you, too.”

December 29, 1941: The dress code for the Shore Patrol was white uniforms, khaki leggings, and a Shore Patrol insignia or brassard, worn on the upper arm opposite our petty officer rating. On our G.I. webbed belt, we carried two extra clips of .45 ammo, a holster, and a night stick. We were also required to carry a gas mask in a khaki bag slung over our shoulders. The gas mask was bulky, a pain to carry, and always in the way. Sometimes, we would hide our gas masks under the bunks or in our lockers, and stuff paper in the carrying bag so it was lighter to carry. If we’d been caught, it would have been our ass.

This day, the Shore Patrol conversation was football and the Rose Bowl game that was to be played three days hence at Duke University in North Carolina. Pasadena was considered too close to tbe Pacific: the Rose Bowl could become a target for an enemy submarine. Oregon State was Duke’s opponent.

The Shore Patrol had an overbalance of easterners and midwesterners: Duke was their favorite.

“Oregon State won’t have any trouble with Duke,” said Moody. “We’ve got the best quarterback and receivers in college football.” Moody had played football for Oregon State a few years earlier.

I said, “Don Durdan, tbe quarterback for Oregon State, was one of my classmates at Eureka High School. He was one of the best quarterbacks we ever bad. Oregon should take Duke easily.”

That football game went down in history as the only Rose Bowl game every played outside Pasadena — and it was won by Oregon State. Don Durdan, the winning quarterback, joined the Army Air Force after graduating from O.S.U. and was killed in a bomber crash during the war. [Ed. note from 2024: No, he wasn’t.]

December 30, 1941: I was partnered on Shore Patrol with Flanagan, a Marine. Our beat area was within walking distance of the Old Naval Station, up Bishop Street, past the Main Post Office, to the YMCA.

“Let’s have a coke,” Flanagan said, and he walked up to the sandwich shop counter in the YMCA. I pulled out my wallet as the counterman poured two Cokes. He waved my money aside. “It’s on the house,” he said. “SPs don’t have to pay.”

Most of my patrol in the months was in the lower section of Honolulu, starting at River Street, up Beretania, to Pauahi, and winding up on Smith, an area where old rooming houses above businesses were brothels.

Honolulu was famed for its cathouses. The military brass allowed the houses to operate openly; the Shore Patrol had to check them out three or four times a day, handling disturbances caused by unruly or drunken servicemen. Six days a week, the houses opened at 1000 and closed at 1600. In most houses, the hookers would tum a trick in less than five minutes. This caused no end of trouble for us SPs: the serviceman always felt he was cheated. Prophylactic stations were set up in a few places to control gonorrhea. And the Shore Patrol doctor, accompanied by an SP, made a weekly check for cleanliness of the girls, their rooms, and the wash facilities. I had that duty twice.

The New Senator rooms, on Hotel Street, had the hookers on a production line. Each girl was set up with three cubicles. The first was for a guy to get undressed, the center contained the bed, and the third was for the guy getting dressed. The hookers never handled money. Built into the wall between the hallway and their lounge was a cabinet that contained a series of boxes. The end of the box facing the hallway had a slot big enough for a poker chip. The box could only be pulled out from the lounge room. The going price, $3, was collected by the maid who then deposited a poker chip, worth $2, in the hooker’s box. When the days’ work was over, the girls — most were from stateside — retrieved their boxes from the wall and counted the proceeds.

On one of our rounds that included the New Senator, Moody and I went up to the hookers’ lounge and had some highballs. That was against SP rules, but it wasn’t the first time we’d broken the rules. One of the girls opened her box of poker chips and counted her money: $120 in one day. In 1942, that was a lot of bucks. Most of the girls’ earnings were spent on diamond jewelry. A merchant came to the lounge, spread the diamonds on a green felt cloth, and the girls shopped. Prices went up to $5,000; diamonds were how the earnings were hidden from the IRS.

February 8, 1942: Sunday. After mass, I was on liberty. I walked to the Honolulu Yacht Harbor on Ala Moana Drive. As I got to the end of the main dock, one of the yachts caught my eye. It looked familiar. It was moored about a hundred yards from where I was standing, a little sloop, about 30 feet long. When the stern swung around my way, I could make out the name. Idle Hour.

In the summer of 1937, the Idle Hour, on a voyage down the coast from Portland, had put into Humboldt Bay and tied up to the Eureka Yacht Club dock. Dwight Long was at the helm. Long was circumnavigating the world, and was docked in Humboldt harbor to wait out a Pacific storm.

Milton Rolley and I had gone to the Yacht Club to secure the Little Lady, our Snipe sailboat. We saw the Idle Hour, and introduced ourselves to Long, a man in his late twenties. He invited us aboard.

“I’ll hit Tahiti and other South Pacific islands.” be said, “then on to Australia and the Indian Ocean, into the Red Sea, through the Suez to the Mediterranean, up to the Atlantic, then from England, to Cape Town, South Africa, across the sea to the Panama Canal, up the Pacific coast to Portland. Itinerary subject to change at any time.”

We were awed. Long estimated his trip would take two and a half years. In 1940. we met Long again. He was back in Eureka, showing slides at the yacht club, to promote his book, Seven Seas on A Shoestring.

Now, in February 1942. as I watched the Idle Hour bob around the mooring buoy, I saw a figure moving in the cockpit. I’d worn swimming trunks under my uniform. I decided the swim wasn’t that far, so I undressed, removed the newspaper I’d stuffed in my gas mask bag, folded my uniform and stored it in the bag. I swam the hundred yards to the Idle Hour, and yelled. “Ahoy! Idle Hour! Permission to come aboard!”

“Permission granted,” a man yelled back. It was Dwight Long; not too much changed, except for more weather-beaten lines in his nut-brown face.

We drank a few beers, and Dwight said he’d been on his way to the South Pacific again, intending to visit New Caledonia, New Hebrides and the Solomon Islands when the Japanese hit Pearl Harbor.

“I’m on the light cruiser, the USS Vincennes,” he said, “the junior navigation officer. We’re pulling out of Pearl soon for the South Pacific. The Idle Hour stays here until the end of the war.”

When the afternoon ended, Dwight rowed me back to the pier in his dinghy. I pulled my uniform out of my gas mask bag, dressed, and the two of us walked to Ala Moana Drive. We shook hands before he boarded the bus to go back to Pearl and the USS Vincennes.

The Vincennes, and the cruisers Astoria, Quincy, and the Australian cruiser Canberra, were sunk during the naval battle in Solomon Islands six months later — on August 7, 1942. One thousand sailors went to rest on Iron Bottom Sound. Dwight Long was among those listed as missing in action. I don’t know what became of the Idle Hour. [Ed. note from 2024: Once again, no. Dwight Long survived the war just fine.]

November 19, 1942: We were loading buses at the railroad station when I heard a voice behind me say. “Ted Gruhn! What the hell are you doing here?”

It was Clarence Smeds, a Eureka friend I’d known all my life. Clarence had a first class electrician’s mate insignia and one hash mark on the sleeve of his white jumper.

“Kelly Smeds!” He was the best friend of my brother Al. Kelly’s younger brother, Howard, was my buddy from the logging train jumping days.

Kelly said that his ship, the USS Farenholt, a destroyer, was in dry dock at Pearl for battle damage repair that had occurred at Guadalcanal on October 11-12.

Kelly said the repairs would take a couple of months, and he asked to me come out to the ship for a tour. November 28, 1941: I found Kelly Smeds in the Farenholt electrical shop. We walked back to the after-deck house, which contained the head and showers, and the ladder that took us below to the berthing compartment. Canvas pipe berths down each hull side of the ship and in the center flanked two passageways to the rear berthing compartment, which held the ammunition handling room for the #4 five-inch guns.

We made our way to the carpenter shop in the starboard stem compartment. The carpenter shop was a small compartment, eight feet wide and twelve feet long, with a wood-topped work bench along the hull side. On the opposite bulkhead was rack for pipe and miscellaneous metal.

Back up on deck. Kelly and I walked from the fantail where the depth charge racks were, to the break of the fo’c’s’le, where the deck rose up several feet to the bow of the ship. Along the way. we saw workmen installing 20 mm rapid fire guns in the newly built gun tubs. Up on the fo’c’s’le, we spotted sailors chipping paint on the deck, Kelly said, “Ted, see that kid who just stood up? He’s from Eureka. Maybe you’ll recognize him.” I did. It was Jack Johnson, Varvel Carter’s nephew who had lived with the Carters, our neighbors.

I tapped Jack on the shoulder. “It’s hard to imagine three of us from Eureka standing on the deck of the same ship,” I said.

Before I left the Farenholt that day. Jack — on the ship, he went by his real name, Roy — told me that a second class carpenter’s mate, Lane, wanted to be transferred. Maybe I could work a swap.

“Ted, do you really want to get on this ship?” Kelly asked. “You’ve got good safe duty now; you can stay on Shore Patrol till the end of this war. The Farenholt is headed back to the South Pacific as soon as she’s repaired. You could get killed.”

December 2, 1942: I was driven in a truck to the Farenholt’s dry dock at Pearl Harbor. Lane, my replacement, was waiting, his sea bag at his feet. We shook hands. Lane climbed in the truck and drove off, and I hoisted my gear and climbed the ladder to the deck of the dry dock and the quarter deck of the USS Farenholt D.D. 491. I presented my orders to the officer of the deck. I was now officially a member of the crew.

And I was on my way to the war.

###

Ted Gruhn returned from the war, and stayed in the construction business for 45 years. He retired as a construction estimator in 1985. He has been married to his war-time sweetheart. Lillian, for sixty years. The Gruhns live in Concord. Ted’s brother, Frank, lives in Arcata; his two sisters, Helen Kline and Marion Murphy, live in Eureka where, for many years, Marion worked for Daly’s. Roy Johnson’s widow. Margaret, also still lives In Eureka.

###

The story above is excerpted from the Winter 2003 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE