A support group, a religious group, a political group, a civic-minded group. The Amity Birthday Club, believed to be the first association of African Americans in Humboldt County, could rightfully claim all of these titles.

In 1952, when Margaret Neloms proposed the idea and Mary Watkins set out to make that notion a reality, it’s likely that nearly all of Eureka’s black residents knew one another. The Redwood Curtain, as many have named the cause of Humboldt County’s relative isolation, worked not only to slow the arrival of the railroad and the Redwood Highway, but to limit the region’s racial diversity as well.

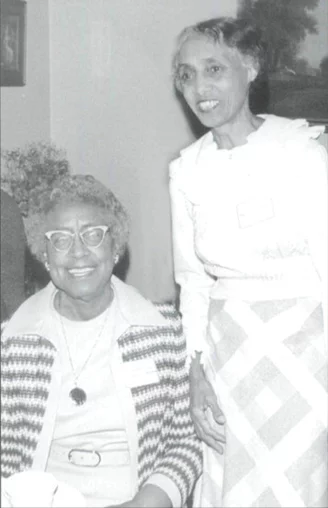

Margaret Neloms (left) and Myrtle Oneal at the February 9, 1975 Amity Birthday Club Scholarship Tea in Eureka. Photos via The Humboldt Historian.

The 1940 census shows just forty-five black people living in Eureka and fifty-two in the unincorporated areas of Humboldt County. By 1950, eighty-six African Americans called Humboldt County home while the number living in Eureka was unspecified. Humboldt County’s African American residents to this day account for less than 1 percent of the area’s residents. Unlike other areas of the country. Eureka had no racially segregated neighborhoods — with the exception of its 19th century Chinatown, which, as many know, was shamefully eliminated in 1885. The inadvertent shooting death of Eureka City Councilman David Kendall, caught in the crossfire of a Tong war, prompted city leaders to demand the exportation of all the North Coast’s Chinese residents.

The few African Americans who chose to make the North Coast their home in the first half of the 20th century had their housing choices limited only by desire and income. Yet, all was not equal. More than a decade would pass after the Amity Birthday Club’s founding before tbe Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 became the law of the land. And, while the North Coast’s white population may have been visibly accepting, the area was not without incidents of racism.

Amity Birthday Club members, seen here at an undated gathering, included (back row) Beulah Hughes, Dorothy Taylor, Margaret Neloms, and (front row) Otelia Johnson, Ruby Desmond and Gertrude Woods.

‘Nothing But White People’

Those of color who braved a move to the predominantly white North Coast may have found themselves feeling a little hesitant about such a change. Dorothy Taylor, who joined the Amity Birthday Club just months after its organization, recalled the trepidation she felt when she and her husband moved from Louisiana to Eureka. Dorothy recalled she and her late husband, Herbert, were convinced by Herbert’s cousin, Tom Woods, that jobs were aplenty in Humboldt County and coming here would be a good idea. moved west in 1943.

“Jobs were hard to find and wages were terrible (in Louisiana),” Dorothy said.

When they arrived. Herb, some may recall as the long-time pastor of the Fields Landing church, quickly got a job working on the railroad for what Dorothy described as “very low wages.” In time and with the effect of World War II, he snagged a job at the shipyards, where he worked until its closure following the end of the war.

But Dorothy remembered the transition wasn’t an easy one.

“I had never been away from home. When we got here, there was nothing but white people,” she said.

Although she missed her home and family. Herb’s cousin and his wife were welcoming and before long Dorothy settled down and accepted her new home.

In an April 10, 1984 interview with the Times-Standard, long-time Eureka City Councilman Jim Howard, then sixty-eight, perhaps best capsulated the climate of growing up black on the North Coast. Howard had been in this area since he was six months old.

“We were the only black family here for a who good many years. Unless I was looking in the mirror, the only other blacks I saw were family,” the Georgia native joked.

In 1973, members Margaret Neloms, Marge Hill, Dorothy Taylor, Mabel Ayers, Myrtle Oneal, and Bernice Stegeman posed at a meeting.

A Club Begins

With the Amity Birthday Club’s founding in 1952, the community’s African American women had a vehicle for regular gatherings to share prayer and socialize. According to a one-page history of the club, “The name Amity was selected because it means friendship, harmony, and warm-heartedness.”

In 1992, long-time Humboldt County resident Ina Harris, one of three white women invited to join the Amity Birthday Club in the late 1960s, donated the club’s records to the Humboldt County Historical Society. Inside the box is a treasure of history and a glimpse into those who were invited to join, the meaning of their club, and its role in a climate where racial diversity was nearly nonexistent.

Membership in the club was much prized . The group’s numbers were kept at twelve or thirteen and joining was strictly an invitation-only affair. The women would gather at each other’s homes on the second Sunday of most every month for an evening of prayer, music, discussion, and, of course, celebration of one another’s birthdays. Charter members were Gertrude Woods, Beulah Hughes, Mamie Turk, Lillian Collins, Edith Howard, Zelma Gilmore, Mary E. Watkins, and Margaret Neloms. They first gathered on Eebruary 10, 1952, at the home of Margaret Neloms. Dorothy Taylor, who still lives in Eureka, said she was invited in the fall of 1952 to join by one of the club’s charter members, Mamie Turk.

Amity member Pocola Givens (in hat) and August Givens (in white jacket) gather with others in this undated photo.

Prayer, Friendship

It would be a mistake to underestimate the religious focus of the Amity Birthday Club’s monthly meetings. Sessions began with a song and ended with a Friendship Circle — friends linking hands in a circle to pray for each other’s well being until they met again. An agenda for the meetings included in the club’s collection, notes that singing of a hymn, the recitation of the Lord’s Prayer, and a devotional with responsive reading would begin the meeting. Various business matters, including the program, would follow. The Friendship Circle, another hymn, and a prayer would conclude the meeting.

“We’d open with a song and prayer and close with a song,” Dorothy recalled, — and a particular blessing: “May the Lord watch between me and thee while we are absent from one another.”

“And we needed it, too,” Ina Harris said.

Only after the meeting was adjoumed would the members hold their namesake birthday celebration. There was a birthday cake, a card signed by all the members and, at least in later years, $5 to spend as the member pleased.

An integral part of the monthly gathering was the program. Those assigned to develop a program for that month would either prompt discussion on a particular topic or person or would invite guest speakers. Ina recalled one such discussion surrounding the great contralto Marian Anderson’s difficulties with a 1939 Easter Sunday performance in Washington, D.C. The Daughters of the American Revolution had prohibited Anderson from appearing in its Constitution Hall because she was black. First lady Eleanor Roosevelt publicly protested with an immediate resignation from the DAR and arrangements were made later for Anderson to sing at the Lincoln Memorial. An estimated 35,000 people attended the concert,

Helping Others

Club members raised money for both local and distant causes.

“The first year, our project to raise money was getting people to write their names on quilt blocks,” a 1978 history of the group states. “They were embroidered by the members, when the quilt was finished it was raffled off, with the proceeds going into a scholarship fund for the Piney Woods College in Mississippi.”

Just two years later that same school — now known as Piney Woods Country Life School — would reach national attention when the school’s founder. Dr. Laurence Jones, was the featured and unsuspecting special guest on the popular 1950s television show. This is Your Life. The show’s host was so impressed with the school that he urged viewers to send in $1 each to support the black boarding secondary school. In a short time, $700,000 in donations had arrived, setting up an endowment whose earnings today cover one-half of the annual operating expenses.

Eureka Mayor Bob Madsen (second from left) and his wife, Jo, along with other guests, came to the Amity Birthday Club’s first anniversary celebration in 1953 at Runeberg Hall.

The Amity Birthday Club’s records provide no clear explanation about why Piney Woods College was chosen nor who was the lucky quilt winner. The local newspapers did take note of the Amity Birthday Club’s first anniversary. The presence of Eureka Mayor Robert Madsen and his wife at the February 1953 celebration in Runeberg Hall may have prompted that attention.

According to one account, “A huge birthday cake was the centerpiece for tables decorated with flowers and punch, chicken salad, and other delicacies were served. A five-piece band furnished music for the occasion. Madsen voiced his appreciation of the club, the only Negro organization in the city, and praised the principles upon which it operates. He also commended the members as good citizens in his Sunday night radio broadcast, ‘This is Your City’.”

Handcrafted and decorated booklets serve as mileposts for the organization’s evolution. Created for each year, the colorful records note the officers and committee chairs, the schedule of meetings for the year, and birthdays and anniversaries of members, as well as addresses and telephone numbers.

For most years, members did not meet in July and gathered in August for a picnic. The booklets of later years would note that the August picnic was a joint gathering with the local chapter of the NAACP, which got its own start in 1954.

In 1959, the Eureka Chapter of NAACP’s Fight for Freedom Campaign was honored in the NAACP’s Crisis magazine. Amity members Dorothy Taylor, Lucy Jones, Myrtle Oneal, and Edith Howard were among those honored.

Joining the NAACP

Many Amity Birthday Club members were also active in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Nearly all of the husbands of early Amity Birthday Club members held active positions in the local chapter of the NAACP. and several Amity Birthday Club members had their own impact on the local chapter of the national organization. On February 18, 1956, the Humboldt Times reported that Robert Neloms would be installed as the president of the Eureka branch of the NAACP on the following Sunday. Herbert Taylor would be vice president, and E. J. Oneal, husband of Amity Birthday Club member Myrtle Oneal, would be treasurer. Board members included Myrtle Oneal and Vinnie Lenor, both Amity Birthday Club members.

Herbert Taylor would go on to head up the local chapter in 1958, according to a March 12, 1958 report in the Eureka Independent. Executive Committee members at that time included Dorothy Taylor, Jim and Edith Howard, and E. J. Oneal. Ruth Beck, a white woman, served as NAACP secretary in 1967 and 1968. Benesta L. McMillan held the same job from 1973 to 1975. while Jim Howard, husband of Amity Birthday Club charter member Edith Howard, served as president of the local chapter for five years, from 1969 to 1973.

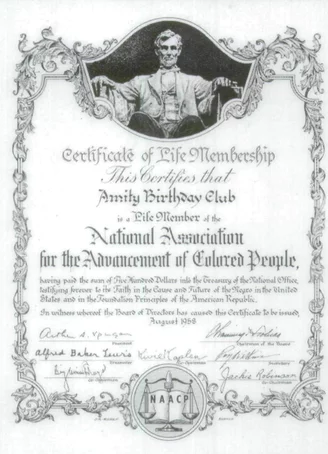

Amity Birthday Club members took great pride in their ability to become life members of the NAACP in 1957. In the March 1957 issue of Crisis, the national magazine of the NAACP, a photo of seven of the Amity Birthday Club members is featured among those who joined for life, a feat that cost $500. The Amity Birthday Club collection at the Humboldt County Historical Society includes the group’s Ceriificate of Life Membership from the NAACP, a glimmering plaque noting the club’s life membership and signed by the national association president, chairman of the board, treasurer, secretary, and two co-chairmen.

Three years later, the local chapter of the NAACP would again make the association’s magazine.

The Eureka chapter’s Freedom Seal Committee and other offices exceeded their FFF quota in 1959. The Fight for Freedom (FFF) Campaign strove to see the fulfillment of the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 be achieved by its 100th anniversary on January 1, 1963. Dorothy Taylor, Lucy Jones, Myrtle Oneal. and Edith Howard, all Amity Birthday Club members, were among those whose accomplishments were noted.

In 1957, Amity Birthday Club members (front row) Zelma Gilmore, Margaret Neloms, Zollie Sanders, (back row) Myrtle Oneal, Ruby Desmond, Edith Howard, and Otelia Johnson, as well as others, joined the NAACP — represented here by Robert Neloms — for life.

New Members

At least ten Amity Birthday Club members were listed on the November 1, 1968 membership list for the local NAACP chapter. Integration of the Amity Birthday Club came not long after the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr.’s message of the need for unity and peace among all God’s children — black or white. Ina Harris, Ruth Beck, and Bemice Stegeman. all white, were invited to join the Amity Birthday Club in 1968, and each maintained their membership for many years.

“Ruth and Bemice and I had been active in NAACP,” Ina said. “We were just thrilled to be invited. It was a very high social privilege.”

Of the three women invited to join in 1968. Ina Harris and Ruth Beck remain in Eureka. Ruth, who resides at SunBridge Care Center, may be more familiar to some long-time Humboldt County residents as the miracle angel of the North Coast children with polio.

During a recent encounter, Ina asked Dorothy Taylor whether inviting the white women in had changed the club. “I don’t think it made any difference,” Dorothy said. “It added strength to the club. We enjoyed having y’all, too.”

“I remember how scared I was at that first meeting,” Ina recalled. She said she remembered thinking why would they want me to join? But. it was an invitation she was quick to accept. And that created memories and friendships that have lasted through the decades.The pattern of inviting women to join the Amity Birthday Club appeared to have been a means to control the size of the group rather than a tool of exclusivity.

“Aside from Benesta (McMillan), none of the rest of us were very high falootin’,” Ina said. Ina fondly remembers Benesta, who joined the Amity Birthday Club not long after being transferred to the area in 1972. A clipping from September of that year reports that Benesta was the new operations supervisor of the Social Security district office in Eureka.

Myrtle Oneal, Zollie Sanders, Clara Nichols, Queen Washington. Alice Crosby, Marge Palms, Otelia Collins, Pearl Davis, Marge Hill, Marjorie Robinson. Zelma Gilmore, Clara Nichols. Vinnie Lenor, Mabel Ayers, Lillian Collins, and Erma Anderson are the other members whose names frequent the club’s records.

Money for Scholarships

Each December, club members would gather with their guests for the annual dinner held in a local restaurant. Members’ husbands were often, but not always, the privileged guests. In the club’s later years much energy was directed to raising monies for college scholarships. For a few years, the funds — raised through painstaking effort — were given to Humboldt State University students. Later, the scholarships were redirected to College of the Redwoods. The criterion was not strictly academics, but designed for those who “were struggling to get an education.” Some recipients were the first in their families to get a college education, others were single parents attempting to better their situation through education. All were, no doubt, grateful for the financial boost. The club’s preference was, according to a newspaper account, “a minority person or lower income Caucasian whose gradepoints are average and is struggling to acquire an education.”

Donations, bake sales, rummage sales, and food basket sales all helped bolster the club’s scholarship fund. While the effort to raise money for Amity Birthday Club scholarships was extremely serious, some of the means chosen provided a little diversion for the members. Twice a year. White Elephant auctions promised surprises and money for the effort. Ina recalls members would find something they had had around the house for quite some time, would put it in a box, wrap it up, and bring it to the meeting. Other members would bid for the mysterious contents. Usually, Ina said, it was “things you would never throw out, but didn’t know what to do with.”

The objects occasionally would do double-duty in the fund-raising world — an item purchased at one meeting might show up at the next auction, re-wrapped and again generating bids.

In February 1975. club members decided to begin holding annual Scholarship Teas — gatherings that prompted coverage in the Times-Standard and are remembered fondly by surviving members. Many of the teas were held at the YWCA — now owned by College of the Redwoods and known as the Ricks House — on the northwest corner of Eighth and H streets in Eureka. These gatherings not only honored students who were receiving the club’s scholarships, but provided an opportunity to raise money for future scholarships. Photos of those events, some of which ended up in the Times-Standard, showed members handing the scholarships to chosen students. The ladies would plan months in advance to properly honor those chosen for scholarships. “Everyone pitched in and helped,” Ina said. “Everyone worked so hard to make it a success.”

Dressed in their finest outfits, members would gather before tables laden with baked goods and silver tea services. “I have nothing but good memories of that,” Ina said.

What Remains

Good memories are nearly all that’s left of the Amity Birthday Club. In the early 1980s, several members moved away and those remaining opted not to keep up the gatherings. The emotional connections, however, still remain. Several former members gathered recently at Ocean View Cemetery in Eureka with the passing of an early Amity Birthday Club member, Myrtle Oneal. Friends and former club members joyfully greeted one another and fondly remembered Myrtle’s many kindnesses and her role as the first African American to serve on the Humboldt County Grand Jury.

###

The story above was originally printed in the Summer 2000 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE