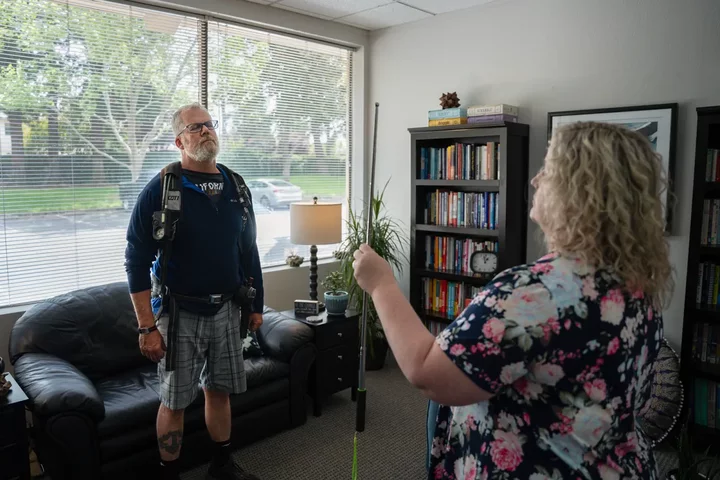

Retired Cal Fire Captain Todd Nelson and his therapist, Jennifer Alexander, conduct a “brainspotting” exercise as part of his treatment that involves Nelson wearing firefighting equipment. Photo by Cristian Gonzalez for CalMatters

With a diagnosis of complex post traumatic stress disorder and wracked by frequent anxiety-induced seizures, Cal Fire Captain Todd Nelson spends much of his days in acute mental distress. His therapist, Jennifer Alexander, said “nine out of ten therapists wouldn’t touch Todd with a ten-foot pole.”

Why? Because of the challenge of treating a firefighter with such a severe mental health condition, including multiple suicide attempts and hospitalizations?

No. Because California’s therapists know that taking on a patient in the state’s workers’ comp insurance system means that it could be years before they are paid. In addition, it’s likely that insurers would challenge their treatment decisions and even subpoena their records.

“If you take a work comp case you knowingly understand that you are not going to get paid for some time,” said Alexander, a licensed marriage and family therapist who specializes in treating PTSD and trauma. Nelson granted her permission to talk about his case. “I have multiple cases in which I haven’t been paid for three years. You have to have a passion to work with this population,” she said.

The intransigence of the system puts doctors in a difficult position — deny patients the care they need or forego their own payment. Like many therapists who fear the impacts of cutting off treatment to seriously ill firefighters, Alexander treats many of them anyway. Then she figures out later how to get reimbursed.

“You have to make a moral-ethical decision — to make a commitment to a client or a commitment to getting paid,” she said. “Insurance gives you a handful of sessions, but with many patients,” like Nelson, “trauma is not going to be resolved in ten to twelve sessions.”

Therapist Jennifer Alexander and her patient, former Cal Fire Captain Todd Nelson, at a therapy session. Alexander says the workers’ comp bureaucracy deters many therapists from treating first responders with PTSD. Photos by Cristian Gonzalez for CalMatters

Some doctors simply refuse to take workers’ comp cases, leaving fewer choices for firefighters and other patients with PTSD and other serious ailments. And a potentially crushing caseload for therapists.

The state’s workers’ compensation system, managed by the California Department of Industrial Relations, provides benefits for private and government workers whose medical conditions are work-related. More than 16 million Californians are covered.

Officials from the industrial relations department refused to answer CalMatters’ questions or provide an interview about issues related to first responders’ mental health claims.

California workers’ comp is an outlier, and not in a good way.

“California continues to experience longer average claim duration compared to other states, driven by slower claim reporting, lower settlement rates and higher frictional costs,” says a 2023 report by the Workers’ Compensation Insurance Rating Bureau, an association of companies licensed to handle workers’ comp insurance in the state.

Only a third of medical losses in California are paid by workers’ comp within two years of an injury, while it’s two-thirds in other states. And about 36% take five years or longer in California, about twice the median in other states, according to the report.

California’s sheer size slows the rate of case closure and reimbursement, said Sean Cooper, executive vice president and chief actuary for the Workers’ Compensation Insurance Rating Bureau. The torrent of claims, the number of attorneys in the system and the complexity of trauma cases bog down an already ponderous bureaucracy.

Because of their cumulative trauma that can stem from an entire career, they often need years of therapy.

Some therapists no longer accept workers’ comp or even private insurance, leaving a patient paying fully out of pocket for mental health care, said D. Imelda Padilla-Frausto, a research scientist at the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research.

“Clinicians often go into private practice because they don’t want to deal with even health insurance. It’s all out of pocket. Then you add workers’ comp on to that, and it’s “oh, no,’ ” she said. “Our health system is administration-heavy.”

Nelson ran smack into that bureaucratic wall. He said he contacted therapists who refused to take insurance or were intimidated by the severity of his diagnosis. “They were being polite, telling me they weren’t taking new patients,” he said.

Nelson, who lives in Nevada City, searched for years for a therapist that would take his case. Experts says there aren’t enough therapists in many rural regions. Photo by Cristian Gonzalez for CalMatters

RAND researchers noted many of these shortcomings in California’s workers’ comp system in a 2021 report.

“The workers’ comp system is excruciatingly slow, doctors are annoyed, not getting paid for extra reports and patients are not getting care,” said Denise D. Quigley, senior policy researcher at RAND and one of the report’s project leaders.

Previous research had identified problems with California’s workers’ comp system, including a heavy burden of administrative costs borne by providers, who also complained about inadequate compensation.

“It’s hard to find providers willing to take on the struggle for workers’ comp. There are some that will just take patients outright, but a majority can’t,” Quigley said. “They recognize that if they take them on there will be self pay, it’s months to get paid, and unless they are part of a really large organization, they can’t cover that cost.”

Nelson recalls traumatic memories of his time as a firefighter during a treatment session. Photo by Cristian Gonzalez for CalMatters

Frustration is winnowing the ranks of providers qualified to treat PTSD and related issues, according to Joy Alafia, executive director of the professional group California Association of Marriage and Family Therapists.

“We have a shortage of mental health professionals overall in California, and with the added paperwork and denials…you can understand why there is a natural inclination to choose a different path. The administrative burden is so great, you need assistance and technology to help overcome the barrier,” Alafia said.

In four years, the demand for mental health care in California will exceed the workforce capacity, according to a UC San Francisco analysis.

Alafia said the administrative burden from workers’ comp sometimes forces therapists to bring on more staff to “wrestle with companies” that reject what doctors view as a sufficient number of patient visits.

That can leave patients vulnerable, Alafia said, which is an unconscionable bottom line.

“We have concerns about continuity of care,” she said. “The more time marriage and family therapists spend doing paperwork means less time with the client. And that’s what people get into this profession to do in the first place.”

###

This story was made possible in part by a grant from the A-Mark Foundation.

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

CLICK TO MANAGE