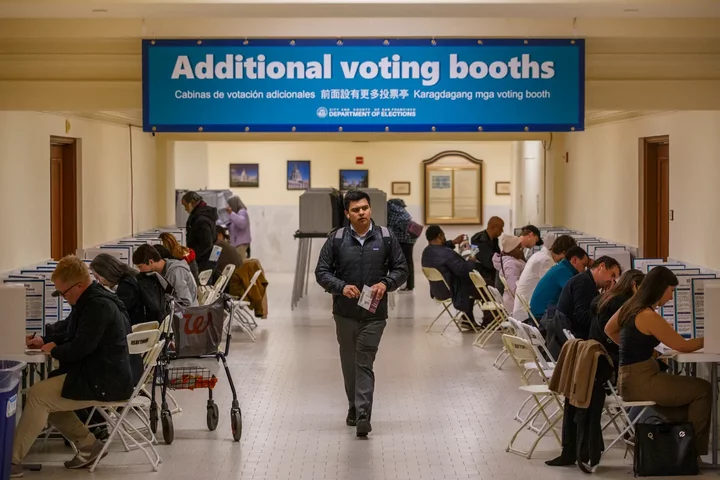

Voters cast their ballots on Super Tuesday at City Hall in San Francisco on March 5, 2024. Photo by Juliana Yamada for CalMatters.

A flurry of dealmaking, largely brokered by the office of Gov. Gavin Newsom, is radically transforming the November ballot at the last minute, with agreements to withdraw a record number of measures before a key deadline this week and potentially even more changes yet to come next week.

Against a backdrop of Democratic anxiety over voter turnout and campaign resources for the November election — where California could play a crucial role in helping Democrats win back control of the U.S. House — Newsom and legislative leaders have maneuvered to reshape the swath of issues that voters will decide this fall.

Over the past week, the governor’s office and lawmakers announced five deals with the proponents of qualified ballot measures to remove them in exchange for legislative action — on employer liability, pandemic preparedness, children’s health care, high school finance classes and oil drilling. That’s more than in any previous election.

Their work may not yet be done. Though very little time remains, Newsom and legislative leaders continue to negotiate over several other proposals that could be added to the ballot next week — before it must be finalized by the Secretary of State’s Office — including bonds for school facilities and climate programs and an alternative to a tough-on-crime measure that progressives detest.

A spokesperson for Newsom refused to answer questions about why the governor’s office has been so involved this year crafting deals on ballot measures.

But there are a range of financial and political considerations for negotiating proposals off the ballot: How an initiative, which lawmakers have little power to amend, might affect the state budget; whether interest groups truly want to spend the millions necessary to wage a fierce campaign battle; and even what the most controversial proposals might mean for other races across the state.

“It has been very active, in part because voters expect their elected leaders to make tough decisions and take action,” Assembly Speaker Robert Rivas, a Salinas Democrat, said in a statement. “The Governor and my Assembly colleagues have done a lot of work bringing groups together and finding consensus, and this will benefit Californians when they weigh-in on important matters at the ballot box.”

This is a relatively new phenomenon in California politics. Before a decade ago, citizen-initiated measures could not be removed once they qualified for the ballot.

But in 2014, the Legislature created a process where proposed initiatives and constitutional amendments could be withdrawn up to 131 days before an election. It was expanded last year to referendums. That opened up a whole new system of policymaking in Sacramento, with lawmakers offering to pass compromise legislation to avert expensive or politically perilous campaign fights.

Some interest groups have figured out how to exploit the rules to their advantage, qualifying sweeping initiatives as leverage to win more modest changes — as in 2018, when soda companies spent millions to place a major anti-tax proposal on the ballot, then negotiated instead for a decade-long moratorium on new local taxes on sugary drinks.

Prior to this year, nine measures had been withdrawn from the ballot after qualifying, according to the political resource guide Ballotpedia. The most for any single election was three in 2018, when initiatives related to consumer data privacy and lead paint remediation were also withdrawn following legislative compromises.

The whirlwind of changes to this year’s ballot began last week, when organized labor agreed to support modifications to a unique state law that allows workers to sue their bosses over alleged workplace violations if business groups withdrew a measure to repeal the law completely. Separately, the California Supreme Court took the rare step of removing a sweeping anti-tax measure from the ballot following a legal challenge by Newsom and legislative leaders.

The governor’s office announced two more deals on Tuesday, with the proponents of initiatives to fund pandemic preparedness through a millionaires tax and expand state funding for health care for critically ill children. In exchange for pulling their measures from the ballot, Newsom agreed to expand the scope of a state medical research program to include technologies related to pandemic prevention and to include more money for children’s hospitals in the state budget.

An association of petroleum companies said Wednesday that it would abandon its referendum seeking to overturn a recent California law creating a 3,200-foot setback for oil and gas wells around homes and schools and challenge it in court instead.

Assemblymember Isaac Bryan, a Culver City Democrat with a large oil field in his district, negotiated the retreat. He told CalMatters that, in return, he agreed to scale back another bill he’s carrying about plugging low-producing wells — which he introduced in part to apply pressure to the oil companies.

“The ballot is often weaponized by those who are losing touch with both the people of California and the people’s representatives,” Bryan said. “That’s where we’re stepping in. We’re doing the people’s business. We’re making sure we’re trying to craft policy solutions that answer the real problems across California.”

The state Senate and Assembly spent several hours yesterday, the final day for proponents to withdraw an initiative, passing bills to fulfill their end of various bargains. After the Legislature approved a measure to require financial literacy as a high school graduation requirement, a personal finance nonprofit executive announced he would pull his similar proposal from the ballot.

Minutes later, lawmakers sent a proposed constitutional amendment to voters that would prohibit forced labor, an anti-slavery policy recommended by the state reparations task force that would primarily affect inmates in California prisons. They also approved changes to another that was already on the ballot, which would make it easier for local governments to win voter approval for infrastructure and housing bonds, reflecting a deal with the real estate industry.

As many as four more measures could be added to the ballot next week as well, if legislators can work through contentious debates that are taking place behind the scenes.

Rivas told reporters that Newsom and legislative leaders are still trying to finalize the details of two $10 billion bonds, one for climate programs and another for school facilities. The extremely narrow victory of a mental health bond pushed by the governor in the March primary has shaken confidence in Sacramento about voter appetite for additional financing measures, but there is tremendous pressure from interest groups that would benefit from the money amid a bleak state budget environment.

“We’ve got to get that work done, so that way we can engage with members to see if we can build support to get these bonds on the ballot,” Rivas said.

After failing to get the proponents of an initiative that would increase penalties for some drug and property crimes to reconsider, the governor and legislative leaders are considering putting forward a competing ballot measure focused on retail theft — though there has been deep division among Democrats at the Capitol about how to proceed as they face rising concerns from voters about crime.

A long-delayed proposal to overhaul California’s statewide recall system, by forgoing the selection of a replacement unless an official has actually been recalled, is also advancing.

And lawmakers are now discussing delaying until 2026 a measure they placed on the ballot to undermine the anti-tax initiative that was recently removed by the Supreme Court. With that fight over, the unions that would have funded the campaign would rather spend their money elsewhere this election cycle.

###

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

CLICK TO MANAGE