When the late Hans Rosling and his co-authors (son and daughter-in-law) published Factfulness: Ten Reasons We’re Wrong about the World — and Why Things are Better than You Think in 2018, it was the book many people were waiting to see. Bill Gates promised to give all university graduates a copy; Kirkus Reviews claimed it was, “An insistently hopeful, fact-based booster shot for a doomsaying, world-weary population;” Nature, not usually given to hyperbole, called it “Magnificent…it throws down a gauntlet to doom-and-gloomers.” Not to be outdone, the supposedly apolitical Nobel Prize Foundation said it would “light up Stockholm every spring…in memory of Hans Rosling.”

Who was this guy who brought comfort to so many, and what did he say that turned otherwise skeptical observers of global trends into optimists? Hans Rosling (1948-2017) was a professor of international health at the Swedish Karolinska Institute, one of Time Magazine’s 2012 “World’s Most Influential People,” and international TED speaker. As a physician, over a 20-year period (before his TED star rose) he studied epidemics in sub-Saharan Africa. It wasn’t so much what he said as what he graphed. His forte was plotting world trends, most of which (and all of which, in his book Factfulness) show the decline of bad stuff and the rise of good stuff. Whether it’s population or crime or poverty or pollution or income gaps or hunger or nuclear weapons, things are getting better. We’ve been fooled by all those pessimistic forecasts, and we should be celebrating, rather than worrying.

Factfulness (“This is a book about the world and how it really is”) starts with a pop quiz. Readers are asked to choose from one of three options: In the last 20 years, the proportion of the world population living in extreme poverty has (a) almost doubled; (b) remained more or less the same; (c) almost halved. The answer is (c) — worldwide, we’re doing much better than 20 years earlier (as of 2018). This should come as a shock, if you’re one of the 95 percent Americans who answered (a) or (b).

So far, so good. Rosling made a good case—in his talks and his book—that, by many measures, things are improving. But (big but) he cherry-picked his data, and in doing so, lost much of his credibility. The most obvious sign of his over-optimism is that there’s not a single graph in the book showing bad things getting worse! No global warming, no sea level rise or acidity curves, nothing about microplastics found in virtually everything these days (including human arteries and sperm), it’s silent on the obesity crisis (the World Obesity Atlas estimated that 51 percent of the global population will be obese by 2035). While pointing to increasing numbers of such “flagship species” as rhinos and tigers, the book fails to mention that we’re in the midst of “the sixth mass extinction:” We’re currently causing species extinction at somewhere between 100 and 1,000 times higher than natural background extinction rates.

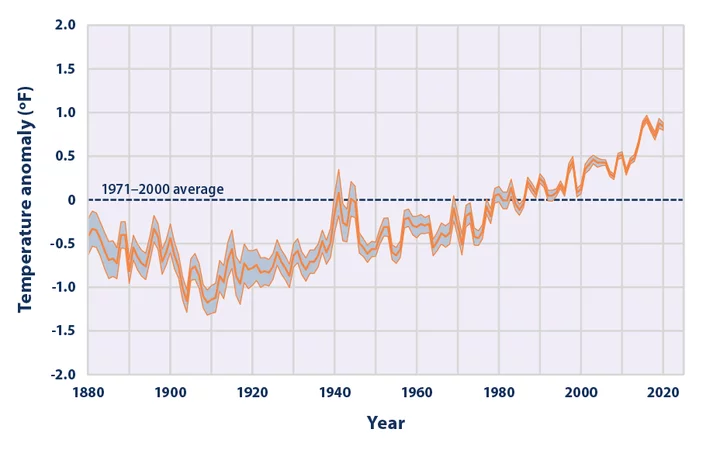

Average surface temperature of the world’s oceans since 1880. More recently, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, “…every day for more than a year, the average temperature of most of the ocean’s surface has been the highest ever recorded on that date.” (Oceans absorb about 90 percent of greenhouse gas heat.) (NOAA)

Apart from omitting what doesn’t support his “things are getting better” case, Rosling bends his data when it suits him. For instance, around the time the book was published, the average income in the U.S. was $67/day, while it was $11/day in Mexico. (It’s improved somewhat since.) To minimize the gap, the authors use a logarithmic income scale; in one stroke, what had been a sixfold difference is barely noticeable!

Then there’s population. According to Rosling and his co-authors, using U.N. figures, the global population will stabilize by 2100 at between 10 and 13 billion people, relying on the notion that, with the reduction in poverty, people will have fewer children. More children currently survive infancy and childhood with medical advances. “Now that parents have reason to expect that all their children will survive, a major reason for having big families is gone,” according to Factfulness, and “More survivors lead to fewer people.” Tell that to those living in the “public health miracle” republic of Egypt, which has experienced a phenomenal reduction in child mortality over the last six decades (30 percent in 1960, 2 percent today). Despite this, the Egyptian population is currently exploding, from 70 million in 2000 to 114 million today. Apparently, it’s harder to change religious resistance to contraception than it is to prevent childhood diseases through vaccination and other public health measures.

It’s easy to find fault with Factfulness, and my impression is that the authors believe that, overall, things really are getting better. And, to their credit, every graph and statistic has a reference cited, all their data is backed up. Me, I can still look around, count my blessings, and feel outrageous gratitude for the sheer improbability of simply being alive. But, you know how it goes: If you’re not worried, you’re not paying attention. IMHO, Factfulness is guilty of not paying enough attention to what may actually do us in.

CLICK TO MANAGE