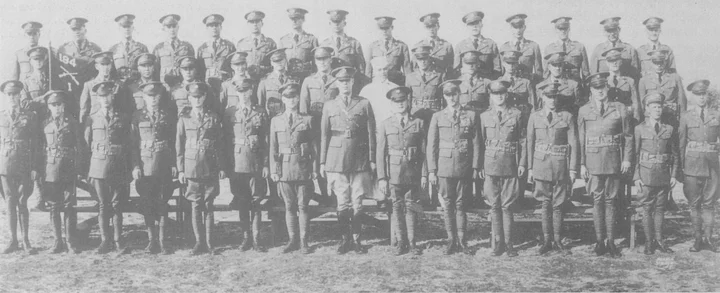

Company I 184th Infantry assembled at San Luis Obispo in 1939. During World War II most of these men saw combat, some in other branches of the service. Of the original Company I men, 13 were killed in action during the war. Photo courtesy A. Clinton Swanson, via the Humboldt Historian.

Company I 184th Infantry California National Guard Unit

was established in Eureka on April 17,

1930, under the command of Capt. Joe

Basier. Capt. Oscar Swanlund assumed

command in 1936. March 3, 1991, will

mark 50 years since Company I was

inducted into the federal service. The

unit was then under the command of

Capt. William Walker.

I became a member of Company 184th Infantry in 1938. That was a period of innocence for most of us as far world politics was concerned. The problems of the Old World seemed far away, and we were desperately trying to find our way out of the long-lasting effects of the Great Depression. A buck private could earn 12 bucks every three months in the National Guard, and it was a strong incentive. In addition he would get two weeks’ vacation at San Luis Obispo at government expense.

I was too young to legally belong to the guard, but with four brothers in the unit, I could not wait to get into it. With the help of certain noncoms and my brothers, I got in. If Captain Swanlund was aware of my age, he didn’t try to stop my enlistment. He was also quite proud to tell later that Company I had I the most brothers within a single company in the state. Our picture soon as appeared in the California National Guard Magazine and that pleased Captain Swanlund very much.

The Henley brothers, shown here about 1938, had the distinction of being the greatest number of brothers in a single company in the California National Guard. From left to right, Edward H., Delton R., Joseph L., Anthony V., and Lucas B. Henley. Photo by Capt. Oscar Swanlund, via the Humboldt Historian.

The armory was in the old Winship School, which forms the west end of the present-day Civic Auditorium. When the auditorium was completed it provided an excellent indoor training area for typical infantry close order drill and general weapons training.

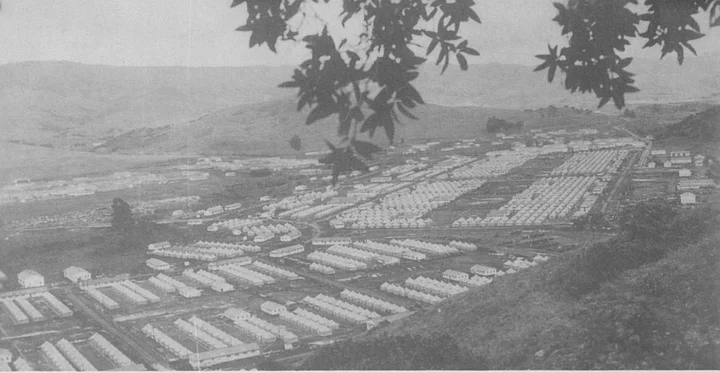

Once each year the company would assemble at the armory and prepare to embark to San Luis Obispo for maneuvers and training. With full field packs we would march to the Splendid Cafe for breakfast and from there to the Northwestern Pacific Depot to board the train for Sausalito. After a trip across San Francisco Bay on the ferry, we would board the Southern Pacific train to complete our journey to San Luis Obispo. Upon arrival we were quartered in Tent City. Along with maneuvers and training that was home for the next two weeks.

Prior to the time Company I was mustered into the federal service, my brothers and I had already entered the regular army. My brother Robert had chosen the Navy — thus we called him “Black Sheep.”

The original men of Company I came from every walk of life. During the war, many went on to gain commissions as officers, some as noncoms, and there were those who earned individual citations. Company I also earned citations as a unit.

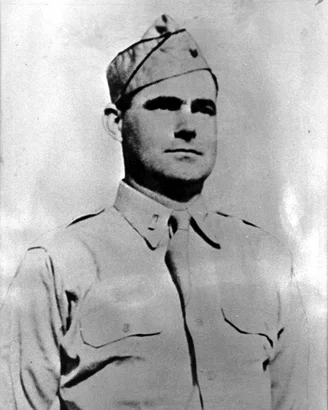

One particularly memorable Company I man was Lt. Robert M. Viale, who was posthumously honored: Congress awarded Lieutenant Viale the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest award that can be bestowed upon an individual, for heroism and gallantry above and beyond the call of duty. During the Philippine campaign Lieutenant Viale sacrificed his own life to protect those of his men and a group of civilians. Uncommon valor was a common mark of Company I men during World War II — as was service to the community in peacetime.

Lt. Col. Ernest J. Reed, a CalTrans engineer, was an original Company I man. He later became the commanding officer of the 1401st Engineer Battalion (combat California National Guard headquartered in Eureka). As Captain Reed he was awarded the Silver Star and Bronze Star Award sometime prior to October 1944.

First Sgt. Fred R. McDonald was also awarded the Bronze Star at the same time. Sergeant McDonald later became a commissioned officer.

Capt. William Walker, a local banker, rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel.

Lt. Col. A. Clinton Swanson, a construction inspection consultant and former assistant director of public works, also commanded Company I for a time.

Capt. Oscar Swanlund, who was the owner of Swanlund’s Photo Shop, reached the rank of major and later served as Mayor of Eureka (1957-1961).

Supply Sgt. Johnny Langer, who was the co-owner of Langer and Kretner, also served as Mayor of Eureka (1947-1951).

Sgt. John W. Phegley, who became a science teacher at McKinleyville Elementary School, continues to serve the community as a photographer and photographic historian for the Humboldt County Historical Society.

Lowell Mengell, Sr., served on the City Council for several years.

These early leaders of Company I—photographed before 1936—were community leaders as well (both Swanlund and Langer later served as Mayor of Eureka). From left First Lt. Oscar Swanlund, Capt. Joe Basier, Second Lt. William Walker, and Sgt. Johnny Langer. Photo courtesy Jack Phlegley, via the Humboldt Historian.

Any many more — too numerous to identify in this article — from every background served their country in peace and war.

The critical need for experienced men drew some of the original personnel into the ranks of commissioned and noncommissioned officers — filling important stations in leadership roles.

San Luis Obispo was the home away from home for the men of Company I during their annual maneuvers and training. When the unit was inducted into federal service, San Luis Obispo was the first camp where they were stationed. Photo courtesy Jack Phegley, via the Humboldt Historian.

Upon induction into federal service the unit was stationed first at San Luis Obispo. They saw service in such places as the Presidio of San Francisco, doing guard duty at the San Francisco Airport. They had maneuvers at places like Chehalis and Fort Lewis, Washington, and in the desert country near Fresno, and were quartered for a time in the horse stables at the Del Mar Race Track near San Diego. They were also sent to eastern Oregon and back to San Francisco before their combat assignment in the Aleutian islands and, finally, the South Pacific.

The 184th Infantry was released from the 40th Division in November 1942 and attached to the Seventh Army Division. As part of the Seventh Army Division, the 184th Infantry saw a wide diversity of action. In May 1943 they were assigned to the Ninth Amphibious Training Force — the Long Knives. On July 12 they embarked to the Aleutian islands. After hard fighting on Attu, they staged on Adak. In a bleak and uninhabited land of frozen tundra and mountains — one of the most hostile natural environments on earth — they prepared for the invasion of Kiska.

Landing at Massacre Bay during the Battle of Attu, May 11, 1943. Photo: Library of Congress, public domain.

Extensive artillery preparation began on August 16,1943, when the order to assault the Japanese installations came. Along with the First Battalion 87th Mountain Infantry, field artillery, and engineers, with a Canadian brigade attached — they landed at Long Beach, Kiska. The commanding officer of the 184th Infantry ordered the band to play them ashore. Thus they disembarked to the strains of “California Here I Come” and “The Maple Leaf Forever.”

On shore, they discovered that the Japanese had vanished — the suddenness of their departure was evidenced by the tables set for mess, blankets soaked in oil but not burned, and many arms left in good condition. A lot of war casualties resulted from mines and booby traps left by the Japanese, but the 184th came away practically unscathed.

The 184th completed its mop up at Kiska and sailed with the Seventh Army Division to Hawaii, arriving there on September 15, 1943. After a period of rest and retraining, they sailed with the Fourth Marine Division for Kwajalein Island.

The camaraderie of the men of Company I is evident in this informal photograph taken while on maneuvers at Chehalis, Washington. From left to right, standing. Warren Moulton, Gus Wetterling, Clinton Swanson, William Moulton and H.R. Sanduski. Kneeling, Carlton Staples, Robert Swanson, Henry Cramer, Ben Dewell, and Williard Washburne (who was killed in action). Photo courtesy A. Clinton Swanson, via the Humboldt Historian.

The 184th Infantry was given the task of seizing Kwajalein, a crescent-shaped island three miles long and one-half mile wide. It was heavily fortified with hundreds of shelters, so well built that it required point-blank artillery fire to penetrate them. In addition, flame throwers and explosive charges were needed to complete the task. On February 1,1944, at 5:00 p.m. a call to halt was made. By that time the 184th had lost 23 men — 10 killed and 13 wounded.

A tropical storm struck at about 10:45 that night, and it was accompanied by an awesome storm of artillery, mortar fire, hand grenades and machine-gun fire. The attack was in the 184th sector, and in the stubborn fighting that ensued, the 184th had 465 casualties — 65 killed and 400 wounded. The Japanese paid the price with heavy losses — 2,000 killed outright and 137 captured.

After completing the capture of Kwajalein and Enewetak, the Seventh Division returned to Oahu and Manus islands for additional training. They then returned to Enewetak to prepare for the invasion of the Philippine islands at Leyte.

The 184th had participated in 91 days of hard fighting during the battle for Okinawa. The Japanese were entrenched in a defensive system of heavily fortified positions.

From their positions dug deeply into the hillsides, coral escarpments and pinnacles — a desperate enemy poised. Though faced with almost certain annihilation, they defended their positions with fanatical and suicidal determination. Counterattacking by ceaseless importunity, they inflicted great casualties upon the 184th Infantry regiment. The battle-hardened 184th fought through rough terrain and inclement weather for 91 days of intense combat. The courage and gallantry of the unit prompted Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner, Jr., to comment, after one of its operations on Okinawa, “A magnificent performance.”

After the campaign at Okinawa, the 184th landed in Korea on September 8, 1945. After a brief reunion with the 40th Division the 184th was deactivated. In January its colors were proudly returned to Sacramento. The remaining personnel were assigned for a time to the 31st Infantry Regiment. Thus the curtain was drawn once more upon a gallant and illustrious California organization.

Countless stories of adventure, terror. supreme human endurance and gallantry are embraced in any infantry regiment engaged in such life or death struggles. The men of Company I — wherever they were assigned — gave a fine account of themselves. Their actions and sacrifices served a critical need in the preservation of the freedoms we enjoy today. At the conclusion of World War II, the 184th Infantry had played a key role in the campaigns of the Aleutian islands, the Eastern Mandates, Leyte, Ryukus and Okinawa.

The 184th Infantry Combat Assault Team was reinforced with tanks and artillery for the invasion of Leyte. made their landing at Leyte on the left of the XXIV Corps on October 20, 1944. It was arranged with the First Battalion (Sacramento, Gilroy) on the left and the Third Battalion (Napa, Santa Rosa, Eureka and Modesto) on the right.

After the capture of the Dulag Airstrip and Burauen, the area from La Paz south to Abuyog and west to the mountains was cleared. Hard battles were fought at St. Victor. Supply situations became serious — shoes worn out from constant duty could not be replaced — and tropical infections and sickness plagued the troops. Still the troops were pushed hard without rest. In November the unit moved to the west side of the island to relieve elements of the 32nd Infantry. Ground captured by the Japanese 13th Division near Demulaan was regained. On December 2, 1944, the 184th, along with the 17th Infantry Regiment, resumed attack. After occupying Ormoc, the area from Delores to Valencia was secured. Christmas Day, 1944, marked the official end of the campaign, yet hard fighting and mopping up operations continued.

The Seventh Division had covered almost 2,000 square miles in its battles of liberation for the Philippine islands. Having conquered 52 Japanese organizations, they had done much to bring about the liberation of the Philippines.

On D day — April 1, 1945 — the 184th landed on the beaches of Okinawa. It They was there that the decisive struggle of the Pacific War was to unfold. Late in May the 184th Infantry spearheaded a night attack, breaking through the Naha-Shuri-Yonabaru line for a distance of five miles — living up to their motto — “Let’s go!”

###

POSTSCRIPT: The history of Company I 184th Infantry Regiment is one of frequent change and reorganization. Its roots go back to the local militias of the days of the Gold Rush of 1849 and to the Sunshine Division, the 40th, which was organized at Camp Kearney, near San Diego, on September 16, 1917, as a unit of the World War I American Expeditionary Forces.

The earliest guard unit to be stationed locally was the Eureka Guard Company Sixth Brigade, formed May 15, 1859. A long list of changes, reorganization, and redesignation took place through the years. It even included the California National Guard Fifth Division Naval Battalion, which began December 7, 1895, and was redesignated the Fifth Division Naval Militia in 1901. After induction into federal service in 1917, it was redesignated as the Fifth Division California Naval Militia. In January 1919 it was deactivated, and there was no unit then for 11 years.

On April 17, 1930, Company I 184th Infantry Regiment of the 40th Division of the California National Guard was formed under command of Capt. Joe Basier. In 1936 Capt. Oscar Swanlund assumed command of Company I. On March 3, 1941, Company I 184th Infantry of the 40th Division was inducted into federal service under command of Capt. William Walker.

After mustering into federal service, the unit was separated from the 40th Division and placed in the United States Seventh Army Division. The unit saw extensive combat on Attu, the westernmost Japanese entrenchment in the Aleutian chain, and in the South Pacific.

On January 20, 1946, Company I 184th Infantry was deactivated in Korea.

After a large number of reconstitutions and redesignations through the 1950s and 1960s, the 579th Engineer Battalion Companies A and B — which you might say are the descendants in terms of military lineage of the 184th Infantry Regiment — were formed as they exist today.

This article is dedicated to those men both living and dead from our own community that shouldered the great burden of war — to establish a lasting profile in our hall of memories.

The author wishes to acknowledge the invaluable assistance in the preparation of this article of former Company I members Lt. Col Arthur Clinton Swanson (Ret), USAF, Lt. William E. Nellist, Jr., Sgt. John W. Phegley, Sgt. Glenn Evans, Sgt. Lowell McDonald and Pfc. Harold Starkey, Veterans of Foreign Wars Service Officer; and Staff Sgt. George Albert, Unit Historian, Company A 579th Combat Engineer Battalion of the California National Guard, and Brig. Gen. Donald E. Mattson, Commander. Center for Military History, Sacramento, California.

###

The story above was originally printed in the September-October 1990 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE