Cal Poly Humboldt’s bachelor’s program offers new opportunity to people incarcerated at maximum-security Pelican Bay State Prison

In less than 15 minutes, Michael Mariscal validated why a team of officials at Cal Poly Humboldt have spent more than three years trying to set up the first bachelor’s degree program at a maximum-security prison in California.

At the end of a class in persuasive speaking, Mariscal was tasked with giving a presentation to highlight his personal growth. His 22 classmates inside B Facility at Pelican Bay State Prison were skeptical: Just two weeks earlier, Mariscal had used his presentation time to give step-by-step directions on how to make a peanut butter and jelly sandwich.

But today was different.

“I’ve never told this to anyone before,” the 32-year-old Mariscal said, holding back tears as he explained his feelings when he learned at his trial that the state was requesting he be put to death. “I said, ‘That’s OK, that’s cool,’” showing no outward emotion at the time, he told the class. But inside his mind was reeling.

“I’m not innocent; I did everything I was convicted for,” he quickly added, referring to a gang shooting that left two people dead.

Mariscal went on to say that his brother had received a life sentence and been murdered while in prison. Mariscal himself was given five life sentences. He declared that he did not expect ever to be released, but finished by saying, “I can still live a meaningful life in here. Freedom is different for everybody.”

A shocked silence filled the room before classmate Darryl Baca spoke up. “That’s some raw stuff right here. I recognize the potential in you.”

“It’s not the first time I’ve cried after class,” the professor, Romi Hitchcock-Tinseth, said later, although she was teaching only her fourth session at the prison.

Mariscal’s speech exemplified everything officials at Cal Poly Humboldt hoped to accomplish when they set out to create a satellite campus at one of the most notorious prisons in the country. They knew that earning a degree could help some men shorten their sentences and possibly land well-paying jobs once released. But they also hoped that the classes, and the camaraderie fostered there, would pay immediate dividends, lessening violence at the prison and improving students’ daily behaviors. Seeing Mariscal address his past while both sharing his feelings and mapping out a hopeful path forward just four weeks into the semester was validating, officials said.

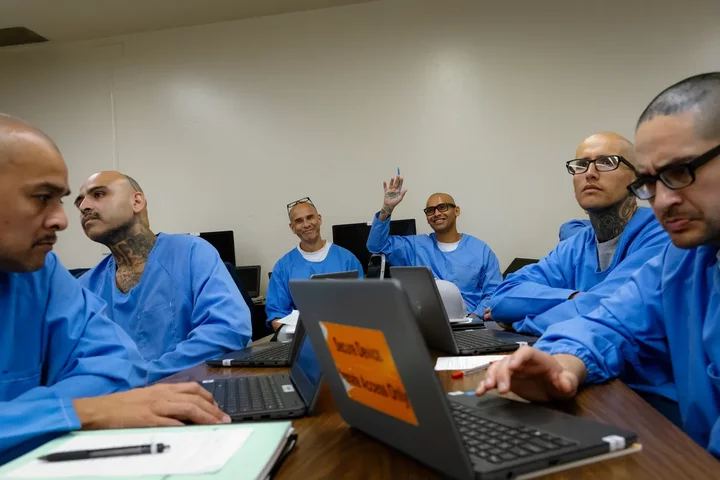

First: Incarcerated college student Michael Anthony Mariscal, 32, center, leaves the education hallway with fellow classmates after school at Pelican Bay State Prison in Crescent City, Calif, on Sept. 17, 2024. Last: Incarcerated college students applaud Michael Anthony Mariscal, 32, after he gave a presentation about his own journey to turn his life around during a CalPoly Humboldt class on persuasive speaking at Pelican Bay State Prison in Crescent City, on Sept. 17, 2024. Photos by Manuel Orbegozo for Hechinger Report

California has been a leader in prison education programs, starting with a 2014 rule authorizing state funding for community colleges to set up programs for students who are incarcerated. Since then, some 25 community colleges and eight universities have established degree-granting programs that now cover every facility in the state. Humboldt’s Pelican Bay program is not only the state’s first bachelor’s initiative at a max-security prison; earlier this year, it became the first program in the country approved under new federal Department of Education rules to let incarcerated individuals access Pell Grant funds to pay for college.

For about 29 years Pell money had been largely prohibited for individuals who are incarcerated, with the exception of a small federal pilot program that debuted in 2015. The new Pell rules made 767,000 people at state prisons nationwide eligible to pay for college with federal funds — starting with a handful of those at Pelican Bay.

“We’re setting an example,” said Tony Wallin-Sato, a former Humboldt official who helped create the program. “If we can be successful at Pelican Bay, it can work anywhere.”

Pelican Bay is one of the most infamous prisons in the country. Built in 1989 in the extreme northwest corner of California, the facility was created to isolate its occupants in two ways. Many of the men who are incarcerated there hail from the Los Angeles area, nearly 700 miles south. And nearly half of the facility’s units were built for solitary confinement, with some occupants stuck inside these 7-by-11-foot cells for decades.

A “60 Minutes” report in 1993 highlighted excessive force by guards, and a 1995 lawsuit exposed inadequate medical care. In 2013, people incarcerated there staged a two-month hunger strike that spread throughout the state’s prisons to protest the excessive use of solitary confinement.

But program staffers and people incarcerated at the facility say day-to-day life there now bears little resemblance to those days. About 400 of the prison’s 2,200 incarcerated men currently take classes that include GED preparation, courses from four community colleges and, now, Humboldt’s new bachelor’s program.

Pelican Bay “used to be one of the most violent prisons in the country. Now it’s not,” said Mark Taylor, a Humboldt official who spent more than 21 years incarcerated before helping to create this program.

In fact, incarcerated students openly drop hints around Kari Telaro Rexford, the prison’s supervisor of academic instruction, telling her they hope she’ll soon bring in a master’s degree program. “I’m trying,” she tells them.

Humboldt prison program ‘makes people safer’

Rebecca Silbert, the deputy superintendent of higher education for the state’s Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, has watched every program that has started in the eight years since bachelor’s degree programs began in state prisons. “Because of the involvement of senior leadership,” she said, “Cal Poly Humboldt’s was the easiest by far.”

Yet Silbert admitted she first tried to talk officials out of creating this program. “Are you sure?” she said she asked them. “It’s easy to be starry-eyed in the beginning, but it’s an endeavor.”

Humboldt’s provost, Jenn Capps, said she agreed with that assessment but pushed on because the program “makes people safer.” Offering bachelor’s degree classes helps “disrupt the narrative” of violence in these men’s lives, making life safer for them, their families, guards at Pelican Bay, and ultimately the public, she argued.

“There are lots of myths out there about people who are incarcerated,” Capps said. “But everybody wants community safety. Offering prison education programs is key to community safety.”

A team of Cal Poly Humboldt officials worked for more than two years before beginning the program in January. The university’s communications department chair, Maxwell Schnurer, taught a class at the prison through the College of the Redwoods to understand why that community college’s program had been so successful. Redwoods began with one course at the prison in 2015, and its program has since mushroomed to 43 courses serving 390 students, said Tory Eagles, the college’s Pelican Bay Scholars program manager.

CalPoly Humboldt communications lecturer Romi Hitchcock-Tinseth discusses a presentation assignment with inmates during her persuasive speaking class at Pelican Bay State Prison in Crescent City, on Sept. 17, 2024. Photo by Manuel Orbegozo for Hechinger Report

As of this semester, the university has ramped up to four classes, each of which are taken by all of the school’s 23 students. Each student had already earned associate degrees and all are now communications majors. Humboldt’s five-year plan is to add other majors and expand to two more of the prison’s four yards, said Steve Ladwig, the director of the university’s Transformative and Restorative Education Center.

Being the first program the federal government authorized to use Pell Grants for incarcerated men put a spotlight on Humboldt’s work. But actually getting those funds has proven to be hard, largely because of the federal Department of Education’s botched rollout of the Free Application for Federal Student Aid, or FAFSA, last year.

Although all of Humboldt’s students are eligible for Pell, only about half of the 23 have had their applications reviewed by the Department of Education so far, said Ladwig. While the university waits for approval of its students’ Pell Grants, it is covering tuition for each student, he added.

When Humboldt staged a ceremony to hand incarcerated individuals their college acceptance letters, Ladwig had to venture to the prison’s solitary confinement wing to deliver Mariscal’s letter, because he was being punished for getting into a fight.

Decades in solitary confinement

Darryl Baca — the student who praised Mariscal after his classroom speech — epitomizes the entire history of Pelican Bay. He came to the prison in 1990, only months after it opened. He spent his first 25 years in solitary confinement, where many incarcerated individuals with gang backgrounds were placed. He was part of the 2013 hunger strike that led to changes in how the prison uses solitary. Now he’s not only a straight-A student, but someone both staff and fellow students look to for guidance.

As Mariscal unspooled his revelation, Baca noticed the seven-minute timer the instructor had set was about to go off and interrupt his speech. From his seat at the front of the class, Baca reached over and deftly paused the timer while handing Mariscal a tissue.

Baca said it took him three tries to earn his GED. Later, he used correspondence courses to secure an associate degree. He continued his education with College of the Redwood’s courses and said he recently passed up a chance to transfer to a lower-security prison because of his Humboldt classes.

“It’s the opportunity of a lifetime,” he said. The college classes have erased the barriers that typically exist among prisoners of different backgrounds, he explained. While classmates support each other, many people at the prison “are making better choices now. The culture has evolved. We’re like a campus now.”

Baca isn’t the only person incarcerated at Pelican Bay who has rejected possible transfers to other prisons. Others said they made the difficult decision to pass up the chance to be moved closer to home and earn a lower-security designation because they wanted to continue in Humboldt’s classes. “I told my family, ‘I want to see you and get closer, but I can’t transfer,’” said Davion Holman, 35, who is originally from the Los Angeles area. Holman, sentenced to 31 years in 2013, told his classmates that before being arrested, he liked school. “I knew I was smart, but I was content being stupid,” he said.

“We take it serious because it is serious,” he added.

Humboldt Professor Roberto Mónico, who teaches a course called multiethnic resistance in the U.S., says at times it feels more like a graduate-level seminar than an undergraduate class. Students are well prepared, he said, with “all the readings marked up,” and they drop in references to the theories of Plato and Aristotle. Yet they can be sensitive about not knowing how to create a PowerPoint presentation or other computer skills because of their lack of formal education.

“If I tell them to read two out of five essays, they read all five,” said Hitchcock-Tinseth. Added Ladwig: “They are phenomenally well prepared to take on a bachelor’s degree.”

Being in a college classroom and able to debate ideas freely is “not mirrored in a lot of other prison experiences,” said Ruth Delaney, who directs the Vera Institute of Justice’s Unlocking Potential initiative, which helps colleges develop prison programs.

Francisco Vallejo, an incarcerated college student with a passion for multicultural resistance courses, poses in front of a mural painted by inmates at Pelican Bay State Prison in Crescent City, on Sept. 17, 2024. Photo by Manuel Orbegozo for Hechinger Report

Francisco Vallejo admitted he struggled when he first began taking community college classes, dropping some before trying again the next semester. But now he hopes his academic progress will bolster his case for parole in 2026. “I had to train to be a student,” he said. “Redwoods gives you the tools, but you use them at Humboldt.”

Student Dom Congiardo said the prison environment teaches people to guard their feelings. But taking college classes shows them “you don’t have to be afraid to open up,” he said. “You won’t be judged for it. It’s all new territory for us.”

Carlson Bryant is another student who declined a transfer to stay in Humboldt’s program. At 41 years old, he’s been at Pelican Bay since 2003, more than half his life.

Bryant said he was scared of the prison’s reputation when he came to Pelican Bay at age 19. “In the beginning, I would have left so fast,” he said. “But there’s too much positive stuff here. It changes you all the way around.”

###

Contact editor Lawrie Mifflin at 212-678-4078 or mifflin@hechingerreport.org.

This story was produced with support from the Education Writers Association Reporting Fellowship program.

This story about prison education was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger higher education newsletter.

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

CLICK TO MANAGE