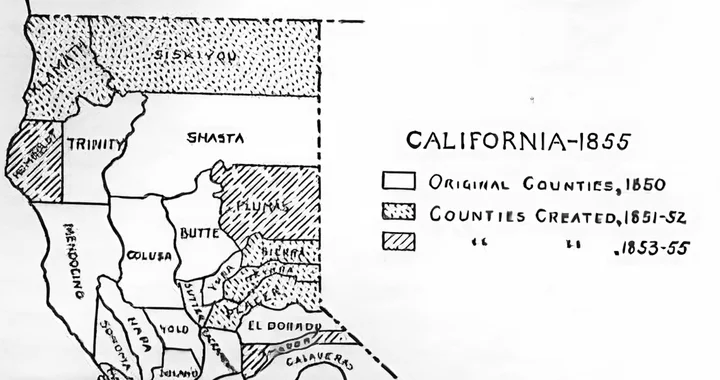

Old map of California counties, with Klamath in the northwest.

###

obscurity: 1. Deficiency or absence of light; darkness. 2.a. The quality or condition of being unknown.

###

The old Washington School in McKinleyville recently received a new coat of paint, and that, unlikely as it may seem, prompted me to recall a bit of the past. The building has long served as a rooming house but in its original guise gave its name to the nearby road, and in the process it obscured a bit of history.

The two lanes of pavement that separate the erstwhile school from the Mill Creek Shopping Center approximately follow an east-west line that appears on the earliest of the area’s maps. The line, drawn in the 1850s, depicted not a road but a boundary, with a then substantially smaller Humboldt County lying to the south and its now all-but-forgotten neighbor to the north.

That other county once stretched from this line all the way to the Oregon border and from the Pacific’s crashing surf to the crest of the Salmon and Siskiyou Mountains. It is the only such unit ever to be disbanded by the state of California — the calamitous county of Klamath.

When it was carved from Trinity County in 1851, Klamath had but two bases for its economy — mining, and supplying the miners. The mines were situated along the Klamath and Salmon Rivers in the vicinity of rough-and-tumble towns like Orleans Bar, Happy Camp, and Forks of Salmon. Their supply points were the ports of Trinidad and Crescent City. Trinidad became Klamath’s first county seat, but by 1854 Crescent City had grown so much that the seat was relocated there by an act of the legislature. Agitation by the inland miners subsequently resulted in the removal of Klamath’s government to Orleans Bar.

The miners may as well have moved the county seat to Mars. Orleans Bar lay more than 50 miles from the coast and offered “no radiating roads, only a wild river and mountain trails” to connect it with the rest of the county. The effect was to overburden what had already become an embattled bureaucracy.

Two years earlier, in 1855, Klamath’s Board of Supervisors reported their county to be $25,000 in debt, with its books in disarray and a substantial sum of money unaccounted for by the sheriff. Despite the deficit, the supervisors had assessed no tax for two years. Faced with these difficulties, the county’s response was to add to the deterioration: in another two years, the debt in the sheriffs account had grown to $32,461.27, which was especially baffling since he was now “absent from the county” and had apparently done little work previously—16 murders had been committed over the last three years “without the least notice having been taken of any of them.” By then the Crescent City newspaper had concluded that “we do not think…the Treasurer himself has ever had any idea how his books stood, much less been able to make any intelligible report from them.” A grand jury was similarly befuddled by the Treasurer’s record keeping but did determine that “the Assessor is delinquent in the sum of $39.”

The handwriting may have been missing from the ledger books but it was on the wall for Klamath: Such unabated deficits and disorder could only be followed by the county’s demise.

The only surprise was that it took as long as it did. Not until 1874 did the legislature finally approve dissolving Klamath, dividing its land, assets, and debts between the neighboring counties of Siskiyou and Humboldt. Even then, a lawsuit by dissatisfied Siskiouians prolonged the agony for two more years before the dissolution became complete.

Today, Klamath’s calamitous quarter-century is no doubt as nearly forgotten as the significance of School Road. The Humboldt County assessor and recorder’s offices house small collections of official Klamath documents, but neither is readily accessible to the public. Our local archives contain no copies of the wonderfully named Sluice Box or any other of the county’s various newspapers. Although some remnants of Klamath’s mining heyday are still visible at Orleans and similar remote spots, the remaining artifacts and architecture leave us a long way from sensing what life was like for Klamath’s challenged citizens.

What we do have to help us, however, are some interesting numbers. The 1870 census gives us a last official glimpse of Klamath before it ceased being a source of statistics. Let us look at a representative set of surveys done in the sector of the Martin’s Ferry post office. The area included a stretch of the Klamath below Weitchpec that was still the province of the miners, and added, to the south, the Bald Hills region that was returning to ranching after a hiatus during the Indian-white conflicts of the 1850s and early 1860s.

We learn first of all that only four types of people were counted — all the whites; all the Chinese (who in this case were all males); all the children who had at least one white parent; and all the Indian women living with white males. Anyone else (which meant most of the Indians) was ignored by the census takers.

Living in the Martin’s Ferry-Bald Hills area were a total of 100 adult males; of these, 68 were white and 32 Chinese. There were no Chinese women and only three white females, but there were 15 Indian women, listed, like their white counterparts, as “keeping house.” Most of the White/Indian couples were unmarried; it is likely that some of the Indian women did not freely choose their living arrangement. White/Indian children outnumbered white children 32 to 8, a four to one ratio. Only one person was more than 60 years old — Bald Hills rancher William Hopkins, 79, whose census entry bore the note “soldier of 1812.” One of the unmarried Indian women, Maggie Hopkins, had her first child at age 15.

I considered this information, which revealed much about how Klamath’s citizens ordered their lives within their chaotic county. But I found my sociological speculations repeatedly sidetracked by thoughts about Maggie Hopkins, pulled so suddenly from her aboriginal adolescence into a motherhood within the world of the whites.

With more research, pieces of her story emerged. The man she lived with was Horace Hopkins, a farmer and former miner, originally from Exeter, Maine, who was 20 years her senior. Horace owned a ranch in the Bald Hills west of Schoolhouse Peak. On the neighboring ranch lived his two brothers and their father, William, the aged veteran of the War of 1812. In the year of the census, Horace reported an amazing agricultural phenomenon on his ranch; after planting, growing, and harvesting a field of wheat, “a splendid crop of oats” spontaneously cropped up. Hopkins swore that the “ground has not been disturbed in any manner since the wheat was harvested.”

Barely more than a year after this miraculous event, the flame of Hopkins’s good fortune had burned itself out. A newspaper account from August 19, 1871 announced a

… cutting affray last Sunday night between A. Shelton and H: H. Hopkins. Report says the difficulty arose over a game of cards, which the parties attempted to settle with knives. We learn from Dr. Lindsay, who attended the wounded men that Shelton is severely cut, while Horace Hopkins is dangerously injured.

Three days later, Horace Hopkins died in Trinidad. His will was probated before the end of the year. He was found to have debts of $1,960.77 and an estate worth $3,000. Two of his nieces, Anna and Ida Butterfield, were named “legatees in the sum of $500 each,” which left less than $40 to be disbursed. Horace’s brother, Albert, was granted possession of the late rancher’s “premises.” Nothing was said about Horace’s two young children, Frederick and Ellen, nor was there any mention of their mother, Maggie.

By the time of the 1880 census Klamath County had joined Horace Hopkins in the ranks of the deceased. The Hopkinses’ Bald Hills ranches were now in Humboldt County, where only one of the original Hopkins clan remained, Horace’s other brother, John. Living with him was his Indian partner, Annie, their own two children, and Fred and Ellen. Maggie fails to appear anywhere in the census.

Here I paused, for Maggie’s fate as the Indian mate of a white settler eerily echoed the story of Willie Childs, the Yurok woman I’d written about in the Summer 1997 issue of the Historian. Not only were they both left with little or nothing by their white partners, but the piece of property that could have been each woman’s salvation was one in the same, for it was the Hopkins Ranch that William Childs later purchased and then willed not to his longtime Indian partner, Willie, but to the white woman he eventually married, Christina.

I began this piece at School Road, seeking to illuminate a small part of Klamath County’s obscurity. But following that road has led me back to a ridgetop ranch site in the Bald Hills and taught me, more than any school could, a lesson about another type of obscurity — of the impulse that prompts a Horace Hopkins or William Childs to take up a knife or pen, and with a slash of anger or a stroke of greed forever alter the lives of those who will live beyond the perpetrator’s own death.

Perhaps in pondering this, we can also consider one last lesson: We don’t have to go to McKinleyville to encounter School Road. We each come to a road that is its equivalent many times in our life, and each time we do, we are given a choice — whether, like William Childs and Horace Hopkins, to cross into obscurity, or, mindful of the fates of Willie Childs and Maggie Hopkins, to cross into light. School is always in session.

###

The story above is from the Spring 1999 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE