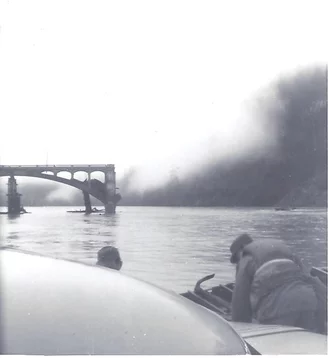

McCovey children standing at the Klamath, looking over the lost Douglas Memorial Bridge.

###

The following is an excerpt from local author Sherry Moore’s new memoir The Raging Klamath: A Playground of Plenty, which is available right now at local bookstores — and lots of other places, too — throughout the region and would make the perfect Christmas gift for the Humboldt History buff in your life. Also on Amazon.

You can also pick up a copy and meet the author at the Humboldt County Main Library in Eureka on Saturday, Dec. 14, from noon to 3 p.m., when Moore will give a presentation and host a book-signing related to the memoir — a story of the river and the people who made their homes on its banks.

###

Chapter 16: The 1,000-Year Flood

The Christmas Flood of 1964 was the worst natural disaster to strike Oregon and Northern California in recorded history. The coastlines were especially hard hit. With sustained flooding from December 18 to January 7, one span of six days registered a total of 30 inches of rain, and a staggering 10,390,000-acre feet of water flowed into the Pacific Ocean from California’s northern tributaries. With the disasters of 1953 and 1955 considered to be 100-year flood, it was not a stretch to call this catastrophic event a 1,000 year flood.

Throughout its life, the Klamath River has always been vulnerable to annual changing weather patterns that cause the river to silt, flush and alter its flow. Before 1953, the most memorable floods on record occurred during the winter of 1861-62, in January 1881, in January of 1890, and the winter of 1926-27.

The flood of 1861-1862 impacted Washington, Oregon, Nevada, portions of Idaho, Utah, Arizona and California. It was the widest-spread, longest lasting, costliest, and harshest on the animals and people, as well as the erosion and lost buildings to California. At the time, there were only 350,000 people living in California, and the cost of rebuilding would bankrupt the state. Named the “Ark Flood” because it rained for 40 days and nights in parts of California. The storms began rolling into Oregon in November and then spread southeastward. Much like 1964, warm weather systems melted high snow packs, causing all streams and rivers to swell and overflow.

Along the coast, San Francisco recorded its highest amount of rainfall ever. Nothing has come close since. Thirty extra feet of muddy freshwater poured into the salt waters of the bay for days, bringing lots of fish for the taking. To the south, masses of snakes from the Sacramento Delta slithered onto farm fields at Monterey Bay. Cattle drowned by the thousands. San Diego’s topography was forever changed from eroding hillsides.

California’s inland valleys, as well as the Mojave Desert, became huge lakes that took several weeks to drain. Sacramento was so inundated that the capital was temporarily moved to San Francisco. Approximately one thousand Chinese immigrants, afraid to leave their cabins, were swept into the Yuba River and drowned. Active hydraulic gold mining operations compounded the erosion. In their book The Great Flood of 1862, authors W. Leonard Taylor and Robert Taylor wrote, “No single industry in the history of California has generated more long-term environmental damage for such a meager economic return.”

A severe two-year drought followed the 1862 flood. Many people suffered, due to a lack of food, shelter, and other necessities. Grasshoppers consumed the parched grasslands. With so much depletion and disappearing wildlife, starving Indians in the hills resorted to rustling cattle, and ignited a war with settlers. The magnitude of cattle lost forced an end to the large vaquero ranches.

From December to mid-January of that same winter, Terwer Valley experienced four episodes of the Klamath River cresting and ebbing. Ten to 15 feet of soil eroded away around Fort Terwer. All 20 of its buildings were lost, forcing most of the soldiers to live in tents. One of the officer’s tents, along with other wreckage included still-edible winter squash, washed up on Crescent City beaches. Nearly a century later, land surveyors found two partially-buried rock fireplaces from the fort at the east end of the Glen near the “Big Tree.”

The Waukell Indian Agency (Resighini Rancheria), was wiped out. Those who dwelt near the river lost homes and food-storage buildings. The narrow road into Terwer Valley was closed-off for several days, leaving Yurok canoes as the only mode of transportation up and down the river.

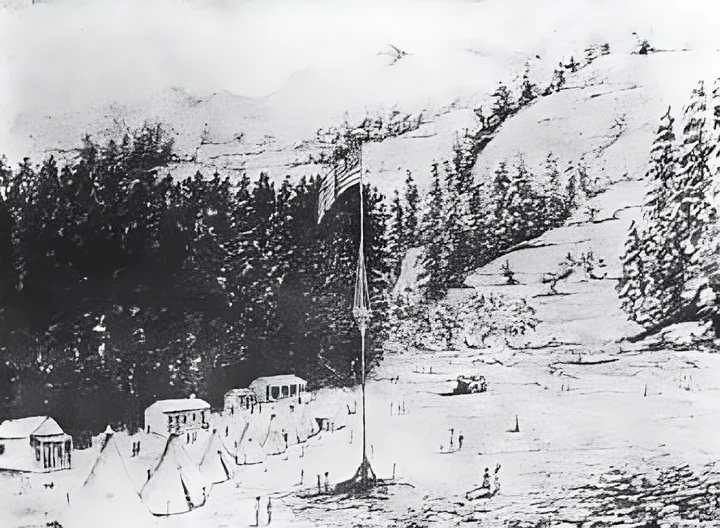

Sketch of Fort Terwer, via the Library of Congress.

With the Klamath Indian Reservation in shambles and the river still running high in March, government officials decided to abandon the fort and agency. Soldiers left Terwer for good on June 10, 1862. Thirty-nine of them escorted Indians to the new Smith River Reservation, 43 miles up the coast. Fort Lincoln was built between Crescent City and the Smith River to garrison the soldiers. The Yurok who stayed on the Klamath were glad to see the soldiers go, even though they got along with them.

The Smith River Reservation continued to grow, with several hundred more displaced Indians coming in from Humboldt County, significantly reducing the Eel River and Redwood Creek Indian populations. Some escaped into the hills, or went back to where they once lived and adapted to the white man’s culture. Indian agent Morgan Tucker, who spoke several Native American languages, stayed at Requa with a couple of soldiers to keep peace for many years.

In 1863, William H. Brewer, a professor of agriculture, visited Klamath and Crescent City. He was amazed at the assortment of trees that had come down the Klamath River and were washed up along the coastline. “They were tremendous in size and length,” he reported. “The eight-mile beach at Crescent City was covered to a width of 200 yards and a depth three to eight feet with debris. There was enough wood on the beaches to supply the timber market for years.”

The next major flood for Klamath happened in January of 1881. According to Morgan Tucker the depth of water was higher than that of 1862 and his experience was similar. Enormous uprooted trees came crashing down the river, homes were lost, and livestock drowned. Upriver, 100 miners from Sawyer Bar on the Salmon River were washed out, and, with no provisions, were soon starving. They made it to Little Ike Camp, a Karuk village on the Klamath River, where they were generously fed dried salmon, deer meat and acorn soup before being supplied with enough provisions to go back to Orleans.

Nine years later, in 1890, another great flood struck. Hunter Creek, a small tributary close to the mouth of the Klamath, was 10 feet deep in some places. At Martin Ferry Bridge, 40 miles upriver, the Klamath rose 100 feet, and carried away the local suspension bridge. The oldest resident there said this was the highest level in his lifetime. His observation is reinforced by Terwer records showing the river crested three feet higher than in 1862.

Fellow friend and woodsman Stacey Fisher, who grew up in Hunter Creek, offered this perspective:

I noticed a large spruce tree at Hunter Creek that had a flood ring around it. The ring was 15 feet above its bottom base. The old-timers said it was from one of the late floods of the 1800s. The 1964 flood didn’t come close. Before the 1964 flood, a couple of loggers were walking in some alders at Starwein Flat on the Klamath River. One logger stumbled over the top of a redwood tree sticking out of the ground. I was called in to dig out what turned out to be a huge old-growth redwood. This tree had been buried for many years from one of the early floods. Some of the outside was rotted, but the tree was basically sound. I dug down over six feet and bucked it up. Three timber-transport truck loads were hauled out.

For the following 37 years, flooding on the Klamath was unremarkable. However, in 1927 flood waters crested just two feet lower than what we would experience in 1953. The new town of Klamath was rapidly taking shape and had a lot of recovery work to do after about three feet of water consumed it. That flood damaged or destroyed all it touched, including Dad’s family restaurant. Small cabins, barns, and fencing went down the river, which stayed high from December to March.

The gravel from under the newly built Douglas Bridge was carried by powerful currents to the sandy islands at the mouth of the Klamath. Safford Island (Bear Island) was heavily eroded. Named for a local fisherman and his family, the island was a popular summertime destination, with cabins and docks. Visitors enjoyed rowing in from the mainland to picnic and fish. A large open field was perfect for pick-up baseball games. Even cows swam over to graze on the thick grass. Occasionally, platforms were erected with lights and a live band for dancing. Indian also performed ceremonial dances. Longtime local resident Mary Larson Wakeman remembered the island this way:

The Charles Gibbon family lived and farmed on the island. They had a nice garden and orchard. Sweet peas and cherries were a favorite. Sometimes neighbor kids, including my dad and his brother, paddled over to the island and played with their kids, showing up for a meal. With 16 children I don’t think their parents even noticed them at the dinner table. Wildlife like deer and bear frequented the island and still do today.

About 15 feet off of the Klamath Glen Road, just before it turned up the hill near McBeth’s, there was an old-growth redwood tree that I estimated to be about 150 years old in 1964. About 18 feet up from the ground, there was a four-inch band of chocolate-colored silt embedded in the bark. The 1964 flood had only come close to its base, so I often thought maybe the river had earlier flowed high on this north side, before changing course to now flow on the south side. Another scenario was that an avalanche had come down the hillside and created a dam near this tree, backing up the water. Without a lot more scientific study and analysis, one couldn’t tell if this was the flood of 1862, 1881, 1890, or another flood before the white settlers came. Regardless, it was a remarkable and perplexing sight.

###

Thirty-four California counties were declared a disaster area in 1964. President Lyndon Johnson designated Northern California a natural disaster area. Californian Governor Pat Brown declared a state of emergency. The US Dept. of Civil Defense, along with the county supervisors and local government agencies had their hands full rendering assistance and aid. Among those counties that suffered the most were Del Norte, Humboldt, Siskiyou, Mendocino, Trinity and Sonoma. Besides the Klamath, some of the other area rivers recording record-breaking heights were the Smith, Trinity, Van Duzen, Mad, and Eel, which crested at mind-boggling 46 feet. Today, travelers on Highway 101 near Miranda have to look well above their heads to see the marker memorializing this measure of a 1,000 year flood. However, the Mad River was two inches below the 1955 flood, because the new spillway at Ruth Lake Dam, despite overflowing and eroding, held back a sizeable amount.

In addition to the town of Klamath, other communities wiped out were Alton, Metropolitan, Holmes, Shively, Pepperwood, and Ti-Bar. Local areas that suffered major damage included Crescent City, Gasquet, Smith River, Orick, Fernbridge, Hoopa, Weitchpec and Orleans. In Oregon and Northern California, a total of 47 people lost their lives, mainly due to drowning, mudslides and helicopter crashes. Three deaths occurred on the Klamath. One was a drowning, a second was due to overexertion, and the third occurred when a Red Cross worker was struck by a helicopter blade at Happy Camp while loading supplies. Within the state of California alone, nearly 2,000 people suffered injuries.

In one way or another, everyone in the disaster zone was impacted. About 5,000 homes, 400 businesses and 1,100 farm buildings were destroyed or heavily damaged. Close to 7,900 families suffered losses in Humboldt and Del Norte counties, alone. Over 8,400 head of livestock, nearly half of them cattle, drowned. Several thousand acres of agriculture land was ruined.

Transportation and general services including utilities, public safety, and road maintenance were crippled. Eighty percent of county roads suffered significant damage, and 16 major bridges washed out. Several sections of Interstate 5 from Washington down to Northern California were closed for a week or more.

The iconic Fernbridge over the Eel River in central Humboldt County was saved by men working day and night removing jammed debris from under the structure with a crane. Further south, when logs began lodging up against another bridge near Scotia, a brave soul ventured onto the pileup with a box of dynamite, and blew it apart. Other bridges were not so lucky, and residents made use of a networks of backroad to get from one place to another. Thankfully, Orick’s Kane Bridge and the Mad River Bridge north of Arcata held, making 101 drivable from the washed-out Douglas Bridge to Eureka. With road and railroad transportation impaired, larger communities like Arcata and Eureka that were outside the flood zone also suffered. Badly-needed supplies were brought in by ocean barges and airplanes.

Highway 299 from Arcata to Redding was closed in many areas, forcing travelers to detour on unpaved backroads. Highway 96 was among the most damaged. From Willow Creek to Yreka, large sections of road and several bridges on the Trinity and Klamath rivers were gone, isolating Hoopa, Orleans, Happy Camp, and several Indian villages.

One-third of Highway 169 from the upper Klamath to Johnson had disappeared. Helicopters and boats were dispatched for emergency situations and supply drops, and gas was rationed. This area suffered the most, and remained isolated for quite some time.

In Del Norte County, the greatest roadway loss was the Klamath Bridge. The Dr. Fine Bridge on the lower Smith River and the Chetco River Bridge miraculously survived, which kept Highway 101 open from Klamath to Crescent City and on to Brookings, Oregon. Highway 199, from Crescent City to Grants Pass, Oregon, endured the loss of three major bridges. Slides in the Smith River gorge were huge, and wiped out several miles of road. It would take months of repair work to open this route.

Bridge damage in the Klamath-Trinity drainage area was unbelievable. Upper Klamath residents reported seeing 100-foot high piles of debris flowing by. The bridge at Willow Creek connecting Route 96 with 299 was completely destroyed. In the Weitchpec-Orleans-Somes Bar vicinity, every bridge was taken out, including the beautiful, prized-winning suspension bridge at Orleans, and the little jeweled-like US Forest Service suspension bridge at Ishi-Pishi. The Martin’s Ferry bridge broke apart in water flowing 115 feet deep.

An eyewitness recalled watching the Douglas Bridge on the lower Klamath give way:

Before the structure failed, debris was backed upstream several hundred feet, although the river level was several feet from the top of the arches. At times, small logs would come hurtling downstream, hit the floating debris, and shoot into the air completely over the structure. The pressure of the river, against the debris, finally pushed 400 feet of the bridge out of the way, and the debris shot downstream with a roar. Another 200 feet of the bridge was left in shambles.

Due to impassable transportation routes and the loss of several thousand jobs, the logging and lumber industry faced a number of challenges. The main source of employment for coastal communities, California was the second largest lumber producer in the U.S. Before the flood, ninety percent of all lumber products were transported by the Pacific North Coast Railroad. Three rail bridges were out, along with 30 miles of uprooted and twisted rail. Some 70 pieces of rolling stock (cars) were either destroyed or missing. It would take 177 days to fully reopen the railroad between Humboldt County and San Francisco. With so much damage to transportation infrastructure, the state had to draw on funding appropriated for Southern California to hire contractors and cover the cost of rebuilding.

Mills shut down or remained in only partial operation for several months. Just getting into the woods to fall timber was difficult, because roads were perilous and weather conditions bad. Millions of board feet of logs and lumber went down the rivers and ended up on beaches and in harbors. Mills that lost timber in the 1955 flood had raised their log and lumber stockpiles at least five feet higher, but that precaution didn’t matter with this flood. Logs weighing 30 tons each were lifted from their resting place and swept downriver like missiles. Hundreds of millions of board feet of timber were lost. The Pacific Lumber Company estimated their loss to be 23,000,000 board feet in lumber alone, plus 18,000,000 in logs.

Well before waters shrank back into their natural banks, help arrived from all over the country. Every branch of the US military was involved, especially the Army Corps of Engineers. Construction workers dropped jobs in other regions to work in flood-stricken areas. San Quentin Prison sent 4,000 inmate workers. Many non-profit organizations in and outside the region contributed greatly, especially the Red Cross and Salvation Army. Those small airports not destroyed were bustling with personnel, vehicles, helicopters and planes rescuing stranded people and delivering supplies such as medicine, food and water. With grasslands layered in silt, and with much hay lost, animals also needed food and medical support. The USDA flew in free grain, and tons of hay. Planes came from as far away as Georgia to assist. Local airports like McNamara Field in Crescent City, Rohnerville Airport in Fortuna, Murray Field in Eureka, and Arcata Airport in McKinleyville were like beehives.

Local people who owned aircraft volunteered assistance. One of them, Les Pierce, told me how he risked life and limb rescuing people and making deliveries in a small helicopter. He recalled flying low in the most dangerous and stormy conditions imaginable, often with no sleep. Once, it was so cold his hand nearly froze to the cyclic stick.

Les, along with all of the other courageous volunteers, should never be forgotten. They operated in virtual war zone, working against Mother Nature to move people out of harm’s way. Small planes even landed on highways to pick up stranded people unable to drive in either direction.

My classmate Dean Hupp, whose parents Aileen and Chuck co-owned Panther Creek Lodge, recalled how his family had left the day before to spend Christmas with relatives in Los Angeles. They got stranded by severe weather in the small town of Garberville in southern Humboldt County. Three days later, they were able to catch a private plane back to Del Norte County. When they were finally able to get to the lodge, little was left. The Hupps and DeVols, two young couples who had pooled their life savings to run a vacation and fishing lodge, were forced to give up on that dream.

Although severely eroded, the Iron Gate Dam spillway on the upper Klamath held, but its powerhouse was submerged, resulting in a lengthy shut down. Every regional dam was near peak flow. The new Trinity and Lewiston dams on the Trinity River managed to hold back a sizable amount of water, and reduced some flooding below. The Trinity River did not break the 1955 flood records because of the 372,200 acre-feet of runoff stored behind the dams. Nonetheless, an impressive 231,000 cubic feet of rushing water per second was calculated at Hoopa. The Klamath reached flows of 557,000 cubic feet per second, and submerged the town of Klamath under 15 feet of water.

Town of Klamath. Photo: James Yarbrough.

At Weitchpec, the water level was 13.7 feet higher than the 1861-62 flood, and 19.5 feet higher than the 1955 flood. Much of this huge increase in height was believed to have been caused by an immense surge in the Salmon River. A massive 2-3-million-cubic-yard landslide six miles up the Salmon dammed the river, then let loose, suddenly amplifying the already-disastrous flows of the Klamath, Trinity, and Scott rivers. According to California High Water 1964-65, published in 1966 by the California Dept. of Water Resources, the North Coast region experienced $190 million in damages — $71 million in the Eel River Valley and close to that in the Klamath River Basin. However, upon further study and evaluation, the overall total cost was later estimated to be $450 million, or the equivalent of $3,510,000,000 today.

Where I lived on the lower Klamath, our community was extremely grateful to have not lost a single life in the 1,000-year flood of 1964. However, the loss of property, jobs, businesses, and, truth be told, our very way of life, created unimaginable hardship. Klamath, Del Norte County’s second largest town with a population of 850, had been erased from the landscape. Three hundred houses, every downtown business, and our beloved bridge had been swept away, with nothing left in town but a few skeletal remains of buildings surrounded by gaping holes. The Terwer-Klamath Glen area, with a population of 1.000, experienced similar destruction. Many of the radar base families also lost their homes. Major Cavalli, commandant of the 777th Radar Air Force Base, immediately arranged for 20 mobile homes to be hauled from Malmstrom Air Force Base in Montana to Klamath. Additional government trailers were brought in for other flood victims, and parked wherever they could find a decent spot — whether a trailer park, a piece of property donated by a generous owner, or, as in my family case, next to the house we would put back together piece by piece.

###

You like history? Consider a subscription to the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE