During the years that Roberts spent in Requa, a brush dance was held each year after the commercial fishing season closed. All photos by Ruth K. Roberts, via the Humboldt Historian.

###

FROM THE EDITOR OF THE HUMBOLDT HISTORIAN: This essay was given to the Historian by Peter Palmquist. It represents the fourth selection from his unpublished manuscript White On Red: Fifty Writings about Native Americans from the White Popular Press, 1850-1950 to appear in the Humboldt Historian.

Palmquist states:

Ruth Kellett Roberts was a society woman from Piedmont, California, who took a special interest in the Indians of the Klamath River area. She regularly arranged for young Yurok girls to live with white families in the San Francisco Bay region and was a strong advocate for Native American voting rights. Beginning about 1915, Roberts spent a total of seventeen summers at Requa, Del Norte County. She was an avid amateur photographer, and many of her photographs are among the best taken of Sa-atch culture. In this essay, which is reprinted from the March 1934 issue of Pacific Sportsman, Roberts talks about the history of Requa and its Native people.

###

Seventeen years ago I stood one day with an old Yurok Indian woman in the Indian village of “Rekwoi” at the mouth of the Klamath River. The name Yurok has been incorrectly applied to the branch of Algonquin Indians living from Weitchpec to Requa. “Sa-atch” is the Indian’s own name for this group. “Yurok” is the Karok (Orleans Indians) name for this group.

The glorious stream, the Klamath River, has its source in Klamath Lakes, Southern Oregon, and flows for approximately two hundred miles through a narrow gorge to the Pacific Ocean, and empties at a point in Del Norte County, California, twenty-two miles south of Crescent City, and seventy miles north of Eureka. The Indians themselves called it “O-meg-waw,” meaning Big River.

The steep slope where we stood above the river had once been a populous Indian community. All that now remained was one old family house, several caved-in sweat-houses, an equally caved-in ceremonial house, graves, and scattered pits overgrown with nettles where houses had once stood. Four Indian families, living in weather-beaten frame houses, were all that remained of the numerous inhabitants of the once thriving village.

We stood for several minutes without speaking, looking across the tidewater lagoon toward the extinct Indian settlement on the opposite hill slope, the site of which was marked only by graves. Above the graves a conical hill, the “Mount Ararat” of Indian legend, stood guard. Suddenly my companion clutched my hand. Quick tears blinded her dim eyes as she exclaimed; “Too bad white man find this place! He never would, if old woman who lived right there hadn’t let fire go out. She made a fog over fire. Hide this place! For long time no one found us! Oh too bad!”

Again there was silence. In my heart I, too, felt it was “Too bad.”

Roberts wrote, “The old town of Requa, clinging to the hillside, with its comfortable inn, church, quaint cabins, and cottages surrounded by gorgeously hued dahlias and sweet peas, seems more like a fishing hamlet in Europe than a California town.”

The first white man to look out across the river and ocean from this same hillside slopes was “Big John” Turner of the Jedediah S. Smith overland exploration party.

The Smith party, the first white “tourists” to invade this now popular fisherman’s paradise, descended the Trinity and lower Klamath River canyons in 1828 and encamped on a flat on Hunter Creek, at a point somewhere near the junction of the Redwood Highway and the county road into Requa. This junction is one and one-half miles in from the mouth of the river.

In Smith’s diary he states that during the short encampment of his party here, he saw no Indians. An Indian informant, however, related to me the fact that many Indians were hiding in the bushes near Smith’s camp and observed, both day and night, every move made by the explorers.

“Big John” Turner, a man of enormous stature, was evidently the only member of the Smith party to go to the actual mouth of the Klamath River. Smith’s diary does not recount this fact, but the Indians do. They have given me a complete description of Turner and the effect upon the Indians of the sudden appearance of this huge bewhiskered white man, who came alone into the Indian village at Rekwoi and stood quietly looking out across the Klamath River mouth and the Pacific Ocean.

The first impulse of the Indians, I am told, was to kill this intruder.

His huge size and calm fearlessness, however, were so disconcerting to the Indians, that they concluded this stranger must have a “medicine” or “power,” and that it might not be safe to kill him. And so, the first white tourist, who came “just to look around,” “looked,” and returned to camp, quite unconscious of his imminent danger.

The next arrivals at Rekwoi came by boat. In 1850 a small bark, the Laura Virginia, anchored just outside the mouth of the Klamath River. This boat was one of several boats outfitted in San Francisco, carrying miners seeking a water route to the Trinity goldfields.

Maps in use at the time indicated a large navigable stream, identified as Trinity River, emptying into Trinidad Bay. It was believed that this river was a direct water route to the Trinity gold fields.

The Laura Virginia, failing to find this river at Trinidad Bay, sailed on up the coast, and discovering the Klamath River, concluded it must be the sought-after water route. Therefore, some of the miners and their supplies were put on shore at the mouth of the Klamath, where a temporary camp was set up on the north beach.

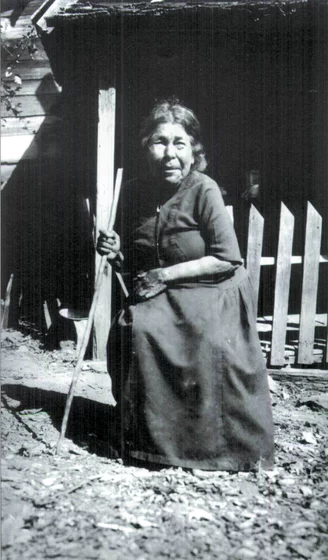

Yurok woman in front of a traditional plank house, which has been propped up and is probably in disuse.

The dismayed Indians watched the Laura Virginia sail off up the coast and viewed with apprehension the camp preparations of the miners. The intent of these white trespassers was unknown to the Indians, but after observing the unwelcome immigrants for a time, decided they were not hostile, and so indicated the desired trails in order to rid the community of an undesirable foreign element.

The Indians called these new people the “Wa-gay,” because they had sprung up from nowhere, and were “smart.” The Wa-gay, a prehistoric people, were, according to an old Indian legend, the first people to inhabit this region, and “knew everything.”

One inquisitive small boy, “Billie” Brooks, and his sister, bolder than the rest, went down to the camp fires of the miners and were treated to baked potatoes. “God, but they tasted good,” Billie, the oldest surviving Indian living at Rekwoi, said, in recounting the story to me eighty-one years after the incident had transpired.

It was these miners from the Laura Virginia who first followed the course of the Klamath River for about one hundred and fifty miles to the Shasta River and made known the fact that the Klamath did not empty into the ocean at the mouth of the Rogue as all maps up to that time had represented its course, but was a continuation of the stream that was known as the “Klamet” above the Shasta River, and had been frequently visited by trappers and settlers who journeyed between Oregon and the bay region of California.

A Yurok woman smiles while several children enjoy the food at a community celebration.

For a period of years, miners and a few prospective settlers struggled through the lower Klamath River region, but made no settlement near the mouth of the river. The first and only building erected in the Indian village of Rekwoi by a white man was a store built and conducted by a man by the name of Weigle. The building housed the trader’s family, a post office, a general merchandise store, a saloon and a community dance hall. Another man named Tucker succeeded the first occupant and the house, and it became known as “Tucker House.”

The woman-shaped rock at the river mouth became known as “Tucker Rock.”

Several years ago an enterprising young Indian, Hathaway Stevens, acquired the property on which the old house stood, razed it and established himself and family in a modern bungalow. He put in a garden, leveled off a parking place for automobiles and prepared to harvest his share of profit from the ever-increasing tourist crop.

The town of Requa, the Mecca for salmon trollers from July until November, snuggling on the hillside about a mile in from the ocean, had a saloon as a nucleus of settlement, and from all reports outrivaled the frontier towns of the movies in local color. The name Requa is the white man’s attempt at the use of the unfamiliar Indian name “Rekwoi,” which in Indian means “river mouth.”

Requa nourished as a prosperous center of business activity and boasted several saloons, two dance halls, two general merchandise stores, a post office, livery stable, cannery and shake mill, until a few years ago when most of the business activity, the fights and the dust of the tourist moved three miles out to the new town of Klamath, near the Douglas Memorial Bridge on the Redwood Highway. The old town of Requa, clinging to the hillside, with its comfortable inn, church, quaint cabins, and cottages surrounded by gorgeously hued dahlias and sweet peas, seems more like a fishing hamlet in Europe than a California town.

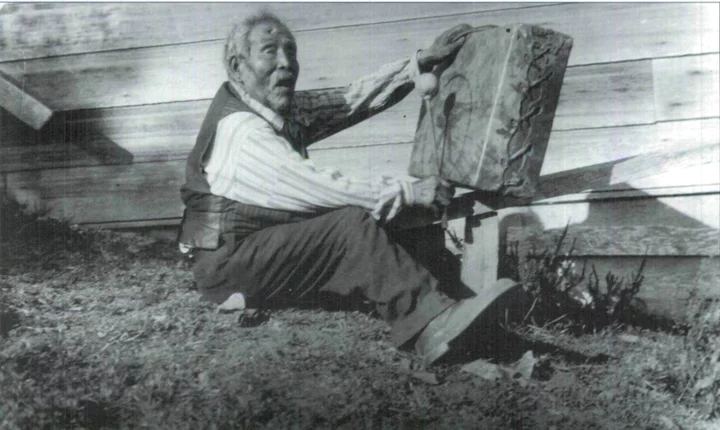

Sandy Bar Bob, a Karuk man, plays a square drum typical of the area.

Fishing has always been the consuming occupation of this community, from the days of the unmolested aborigines who fished with every manner of net, spear, bone hook, and trap, to the familiar commercial net fisherman, and the tourist sportsman with troll and casting rod.

Commercial fishing was introduced on the Klamath River by Mr. A. Bomhoff in 1887, who by agreement with the soldiers in charge of Indian affairs for this district, built a salmon cannery at the present site of the Klamath River Pacers’ Association plant, with the understanding that only Indians be employed as fishermen and for unskilled labor. It was because of this agreement that the Indians and the Hoopa Indian agent permitted the cannery to be built on Indian land. Some of the Indians who started work in the cannery in 1887 were in 1933 employed there, and opening day each season found them knife in hand in their accustomed places ready for work. Commercial fishing was made illegal by action of the state legislature of 1933 and the law became effective January 1, 1934.

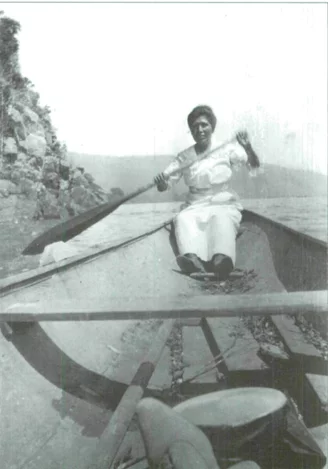

During its six weeks of operation the commercial cannery was the center of community activity. Indian families came down from “up river” in dugout-canoes, skiffs, and motor boats and established themselves for the fishing season in the cannery cabins near the plant. With their arrival the sleeping hillside slope became alive with babies, dogs, white washings and men busy at their net racks putting their nets in order.

Young and old Indians of both sexes fished and worked in the cannery. Gossiping old women, too old to work, took care of the babies and busied themselves gathering and smoking salmon heads and tails, salvaged from the cannery, for winter food.

In the evening, Indians, local whites and tourists gathered on the cannery platform or perched on points of vantage above the river, from which a good view could be had, and watched the fishermen “lay out.”

At the signal whistle from the cannery the fishing boats pulled out from both shores of the lagoon, the gill-nets stretching out behind with the “corks” bobbing on the surface as the boats raced toward the center of the stream. It was a thrilling sight.

Gill-net fishing on the Klamath River in recent years was legally confined to the two-mile stretch between the mouth and Douglas Memorial Bridge, and was done only at night, six nights a week, over an actual period of about six weeks.

At the end of the commercial season, September 6th, the Indians had a grand finale in the way of a “brush dance,” a “white man’s dance,” and a general holiday from all restraint. They “settled up,” bought their winter food supplies and clothing, and returned to their homes up the river. Here they harvested their beans, potatoes and corn, gathered acorns, went hunting, and dried salmon.

To the tourist salmon means sport fishing, to the Indian his staff of life …

Wildflowers bloom along a path that winds across the gentle hillside.

###

The story above is from the Summer 1999 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE