Camp Weott on the Eel River was home to many fishermen. The double-ended rowboats, made of redwood, were used in netting operations. The 1955 flood destroyed the fish camp. Photos via the Humboldt Historian.

Author’s note: This story will be understood best if two “housekeeping ” items are cleared up at the outset.

First, the term fishery as used here refers to a single combined entity: the fish resource, its environment, and the people who use the resource. It does not mean hatchery.

Second, this is not a technical paper Much of the local information was found in the works of Humboldt authors Denis Edeline, the late M. A. Parry, Duane Wainwright, and Susie Van Kirk; these authors reported information gleaned from Humboldt County newspapers, principally the Humboldt Times and the Ferndale Enterprise.

The Beginning Years

Eel River salmon have been the Humboldt Bay Region’s premier fish from time immemorial.

Salmon was a major staple of the aboriginal Wiyot Indians’ diet, and when the earliest white settlements were established along the river commercial salmon fishing began almost immediately.

The first extensive commercial salmon fishery on the Eel River was established in 1853 by Jesse Dungan, a successful former gold miner who had bought a 300-acre ranch in the lower Eel River valley. Other commercial salmon fishermen soon followed, often forming partnerships. Pioneer firms fishing the estuary in 1859 included Dungan & Denman, John Mosely, Martin & Plummer, Gilman & Skinner, William Ellery & Bro., Thomas Worth, Parcells & Nicholson, and Dickerman & Miller. They operated from the mouth of the river upstream to the head of tidewater — near the present Fernbridge.

The arduous work of a seining operation required crews of ten to fourteen men.

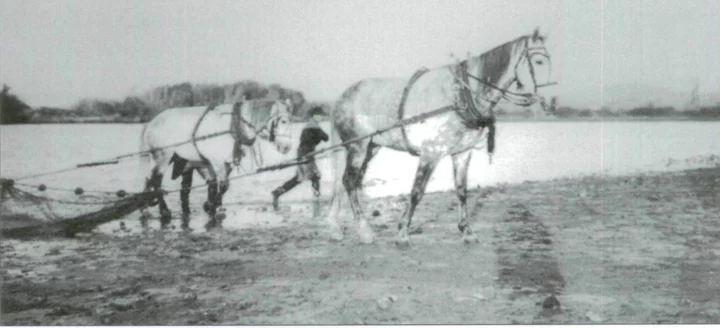

Seining operations on the lower Eel River required a snag-free, gently sloping streambed for the teams of horses to draw ashore heavy nets full of salmon.

In late October 1859, the editor of The Humboldt Times was immensely impressed when he toured the fish processing establishments by rowboat. The industry employed about a hundred men, he reported, and promised to contribute more than $60,000 to the county’s economy during the coming year — a significant amount considering that the county population totalled about 2,700 at the time, and fishing was a subordinate industry.

The editor saw plenty of fish. As he and his oarsman approached the mouth of the river, where the ocean surf was rolling in, “our eyes were greeted,” he reported, “by the appearance of thousands of huge salmon leaping out of the water, as if suspecting the silent element through which they were so rapidly passing to captivity and death.”

The pioneer fishermen were generally local farmers, or they obtained fishing rights from other farmers. Once structural facilities and equipment were installed and working, fishing became a part-time occupation. The annual fishing season usually lasted only three or four months each year, including time for preparation and clean-up — less when heavy autumn rains made fishing impossible, and sometimes destroyed processing plants. Except for laws in 1855 and 1859 that specified fishing seasons and landowners’ rights, the industry was essentially unregulated at first. Subsequent laws further restricted where and when fishing was permitted, and the mesh size of nets; by 1887 commercial fishermen had to buy licenses. Such laws were rarely enforced, however, because Humboldt County citizens, like those in other California salmon fishing communities, considered state regulation an unwarranted intrusion into a man’s right to fish. An accused violator needed only to plead not guilty and demand a jury trial. Convictions were rare in those early days.

Fish were commonly taken in seines more than 400 feet long and twenty-seven feet wide, which were swept through channels by crews of 10 to 14 men, and drawn ashore with their captured fish along gently sloping stream banks. Teams of horses or mules were commonly used to haul in the nets. Fishing firms were relatively independent, constructing their own storage vats and barrels for packing fish on their property from readily available seasoned spruce lumber. Salt shipped from San Francisco was the principal import of the original salmon processing plants.

These firms shipped their salted fish to San Francisco via circuitous routes around or over Table Bluff to ships loading in Humboldt Bay. Later, many thousands of pounds of fresh and processed salmon were also shipped by steamers such as the Mary D. Hume directly to San Francisco from Port Kenyon, on the Eel estuary.

The Fishery Finds A Broad Market

The Eel River salmon industry — which had quickly become the jewel of the Humboldt fisheries — thrived for many years. A trade journal in San Francisco reported in April 1858 that great quantities of Eel River salmon were being exported to Australia, China, the Sandwich Islands and New York, and sold quickly at good prices. Eel River salmon production in 1857 — 1,200 barrels after excluding a significant quantity sold fresh or smoked — equalled that of the Sacramento River, and far exceeded the combined Columbia River and Vancouver Island production. High production numbers were reported occasionally into the early 1900s; in 1904, for example, 345,800 Eel River salmon and steelhead were taken.

Shallow-draft steamers like the Continental, the Weeott., the Ferndale and the Mary D. Hume carried millions of pounds of Eel River salmon and other valley products from Port Kenyon to markets in San Francisco.

The quality of local salmon was superior as well, ostensibly because the fish were caught in saltwater or within the estuary, and were more readily preserved. Records of exports of Eel River fish to foreign markets did in fact show that the local product commanded $10 or more per barrel, compared with $8 per barrel for Sacramento fish. Some New Yorkers, The Times reported in 1869, found Eel River canned salmon the “most delicious they had ever eaten.”

“Fresh salmon are plenty with us now,” a Times reporter wrote in October 1858, “and the packing establishments are busy putting them up.” His words seemed to encapsulate the glory years of the Eel River commercial fishery, which lasted until about 1890. During that auspicious period, local newspapers reported that “jolly fishermen” were “all at work with a vigor,” gearing up for a good year; facilities were being expanded; new firms were being formed; processing plants were operating at capacity; and the fishery was contributing richly to Humboldt’s economy. Port Kenyon became a promising shipping point for southern Humboldt farmers and fishermen. Although a few bad years were reported as well, and overall decline of the resource was noted during the 1880s, the principal worry of local fishermen was that early rains might cut short the fall season, or floods might wash away their facilities.

Perplexing Numbers

In small print on the margin of A. J. Doolittle’s 1865 Official Township Map of Humboldt County, we find this reference to Eel River salmon; “In the fall of 1851, 20 bbls. [barrels] of salmon were taken in one haul; in 1861, 140 bbls.” The average size was “from 10 to 40 lbs.; largest caught, 65 lbs.” In a cryptic afternote, Doolittle reports; “…yield of 1864, only 200 lbs.” That would have been one barrel or less of salted salmon.

Doolittle’s report lends itself to different interpretations. First, he seems to suggest that the salmon resource was essentially depleted by 1864. If so, he was incorrect, because huge hauls were made in subsequent years. In 1878, for example, one seine captured 4,600 fish in one day. The fishery did become commercially unprofitable, as Doolittle foretold, but not until many years later. Fish buyers and sellers were making money until well into the twentieth century, although they had to survive occasional bad years, and salmon abundance was in general decline.

Second, Doolittle might have been demonstrating the great, often mysterious, variations in salmon numbers experienced from year to year. If so, he was right on target. Salmon abundance — then as now — seems to defy prediction: it tends to rise and fall independently of any single factor affecting salmon survival. Weather, rainfall (in past as well as current years), river and oceanic conditions, numbers of nets in the river, market trends affecting fishing effort, condition of spawning habitat — these were some of the factors that determined the numbers of salmon migrating or taken in a given year.

A few numbers will illustrate this variability: Estimates provided by the Humboldt County Department of Public Works show that between 1857 and 1861, the salmon catch dropped from 44,688 fish to 2,600 — nearly ninety-four percent. Many years later, in 1877, 585,200 fish were taken, more than thirteen times as many as the 1857 base figure; and during many subsequent years, catch figures were well above the 1857 base.

The Canneries Cast A Shadow

Although masked by the puzzling fluctuations of salmon numbers and market behavior, the ebullience of the early years gave way gradually during the 1880s to disturbing reports: declining catches, longer nets with smaller mesh being used, markets being developed for small salmon and “half-pounder” steelhead, commercial fishing operations extending upriver into spawning areas, veteran fishermen quitting the river, and public clamor for increased governmental regulation. Sport and commercial fishermen blamed each other, the Indians, the Chinese, and “renegade whites” for the decline. In 1897, the Times blamed them all: the decline of salmon stocks, in the editor’s view, was “wholly accounted for by the interference of men” who prevented the fish from reaching their spawning grounds.

California Fish Commissioners encouraged the introduction of carp, shad, and other exotic species in waters throughout the northern counties to replace disappearing native fish stocks. Most of all, they touted artificial production as the panacea that would save California salmon, and after much local urging they ultimately built two hatcheries and four egg-taking stations on the Eel River, one of them in 1897 on Price Creek, just upriver from Grizzly Bluff. Ironically, the Price Creek hatchery had to import four million Sacramento River salmon eggs when it opened, because fishermen would not let enough fish get past their nets to reproduce native stocks. (This supplemental source of eggs for Eel River hatcheries “dried up” by 1920, when Sacramento River stocks also became depleted.)

Canneries were the major visible factor that pushed the fishery into a decline from which it would never recover. During their existence on the river, most notably between 1877 and 1889, canneries produced an average of 8,100 cases of canned salmon each year. (A case was forty-eight one-pound cans.) Because it took two pounds of fish in the river to produce one pound in the can, that works out to more than three-quarters of a million pounds of salmon extracted in an average season.

Before canneries became fully established, commercial salmon fishing, as noted above, had been dominated by a handful of seiners — probably never more than eight (and sometimes fewer) during any given year because of the special riverbank conditions required for seining.

The Loleta historian M.A. Parry reported how the canneries changed this picture. Fishermen no longer had to process the fish they caught; they sold them in unlimited numbers directly to the cannery. Gillnetting (ensnaring fish by the gills when they tried to swim through a net), which had been practiced by Indians all along the North Coast since ancient times, and to some extent by immigrant white fishermen on the Eel, soon became the common way to fish. Gillnetting was more cost-effective than seining because one or two fishermen in a boat could handle a gillnet, and gillnets worked where seines could not be used. By 1889 gillnetters were making more money than seiners. By 1913, when seining was outlawed, more than half the season’s catch was taken by the hundred or more gillnetters working the Eel River — and the number of gillnetters soon soared to perhaps 150 after the demise of the seiners. Complete sets of nets, floats, line and mending shuttles and twine were sold at Van Duzer’s general store in Loleta.

Several other factors affected the Eel River commercial fishery as it wound down. First, in 1898 the mild-curing process was developed. This process, in which salmon were preserved by refrigeration after light salting (sometimes utilizing a secret formula called “Preservaline”), found its way to Humboldt fisheries in 1905. Since fish so preserved commanded higher prices than ordinary salted salmon, fishing escalated. Also, from 1916 onward, offshore commercial trolling, as well as salmon fishing within Humboldt Bay, took incalculable numbers of Eel River-bound salmon.

Cutting and widening of main river channels and destruction of spawning habitat caused by Humboldt’s burgeoning lumber industry were undoubtedly a significant factor in the fishery’s general decline also. The “reclamation” of thousands of acres of estuarine marshlands and damming of major sloughs to create farmland, which reduced food supplies for juvenile salmon and steelhead, were other important factors.

These factors were not recognized as threats to the fishery at the time, although one irate Port Kenyon shipper went to court against riparian farmers along the lower river (Robarts v. Russ, et al.), claiming irreparable damage to Eel River navigation.

The Final Decades

Around the turn of the century, as Humboldt’s population continued to expand rapidly and transportation in and out of the county improved, new markets for salmon opened up.

Fresh fish buyers representing San Francisco and Oregon firms set up shop along the Eel River estuary, packing salmon in ice for shipment. These buyers were particularly active when markets for Sacramento and Eel River salmon were glutted. Many of them were former Eel River commercial fishermen who provided boats and nets for fishermen and paid as little as one or two cents a pound for their catches, with a daily limit of 500 pounds per fisherman. Between 1898 and 1913 fishermen attempted several times to unionize and force prices higher. They succeeded to some extent, but salmon numbers continued to fall to the point that fishing at any price was often a losing proposition.

By the 1910s the Eel River commercial salmon fishery was obviously a dying entity: the fish resource was depleted, its environment was seriously damaged, and fishermen were losing money. Thousands of Humboldt citizens petitioned the legislature to close the river to netting and save the remnant salmon runs as a tourist attraction. The expanded California Fish and Game Commission — whose predecessor, the Fish Commission, had traditionally pushed for more stringent controls — opposed such a move, however. It permitted the fishery to stagger along marginally for a few years on the grounds that Eel River salmon were needed to help support the World War I effort. (Intensive hometown lobbying by Humboldt’s commercial fishermen, who practically gave away tons upon tons of fresh salmon to the public, undoubtedly influenced the commission’s decision.) Finally, after years of pressure from sports fishermen and conservationists and beefed-up law enforcement, gill netting on the Eel River was declared illegal, effective January 1, 1922. An insignificant commercial troll fishery was permitted on the lower river during September, October and November for a few years after that.

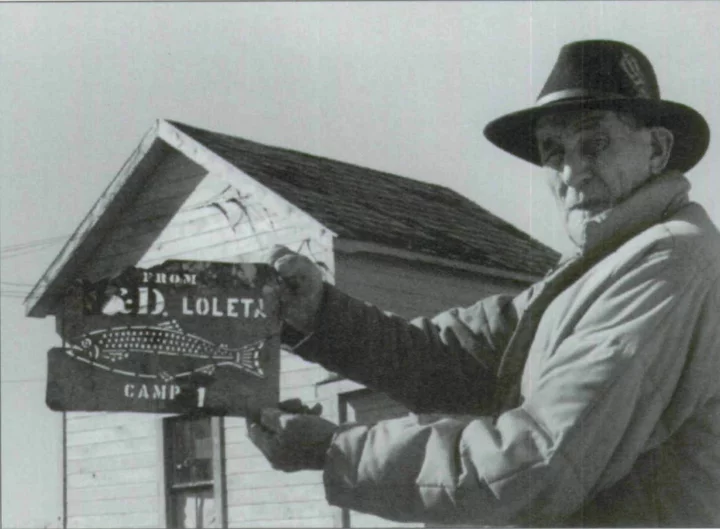

Charles Pedrazzini displays a brass stencil that was once used to mark barrels and boxes that were packed at Camp 1. The initials F & D (partially corroded away) stood for Ferrara and Davidson, buyers for the Western Fish Co. of San Francisco, who were based on land that belonged to the Pedrazzini ranch. Pedrazzini plowed up the stencil in a field many years ago.

By 1926 the gillnetting ban and other restrictions on market fishermen — including a new law permitting wardens to employ “dollar-a-year men” empowered to arrest law violators — had effectively terminated the in-river commercial fishery; from that point on, commercial salmon fishing was legally confined to offshore trolling.

With the commercial enterprise thus eliminated, sportfishing for salmon quickly dominated the lower Eel River. Loleta entrepreneurs such as Joe Rose and Rasmus Svendsen bought up commercial fish buyers’ docks and rowboats, and established boat rental services for the hundreds of sportfishermen who trolled their highly polished copper spinners for salmon every fall on the Eel River.

###

The story above is from the Summer 1996 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE