Andrea Zeppa, homeless services regional coordinator for Alameda County Healthcare for the Homeless, and Deidra Perry, far right, program financial manager for Alameda County Healthcare for the Homeless, team up during Alameda County’s 2024 point-in-time count in Berkeley on Jan. 25, 2024. The PIT count, which included a voluntary survey, gathers data on the county’s homeless population. Photo by Loren Elliott for CalMatters.

New data shows nearly 186,000 people now live on the streets and in homeless shelters in California, proving the crisis continues to grow despite increasing state and local efforts to stem the tide.

That’s according to an exclusive CalMatters analysis of the latest results of the point-in-time count, a federally mandated census that requires counties to tally their unhoused residents over the course of one night or early morning in January.

The count is up slightly from last year’s tally of about 181,000, and up 8% from 2022 (the last year most California counties counted people living in encampments). But there’s some good news: The rate at which the homelessness crisis is growing appears to have slowed. It grew 13% between 2019 and 2022, 13% between 2017 and 2019, and 16% between 2015 and 2017.

And homelessness actually dropped significantly from 2022 in at least nine counties – bucking what for some was a yearslong trend of increases. At least four other counties saw their populations remain relatively steady.

CalMatters’ analysis is based on data from the 32 counties that have reported it so far this year.

In counties that made progress this year, officials say they added more shelter beds and affordable housing – much of it through federal funding related to the COVID-19 pandemic or other new state money.

“Folks got serious,” said Kari Howell, a program manager for the Homeless Services Division of San Luis Obispo County, which saw a 19% dip in homelessness compared to 2022. “Service providers started to get the support they needed from local communities that allowed them to further expand the work they were doing. I think we’re really proud, while also simultaneously acknowledging there’s so much more work to do.”

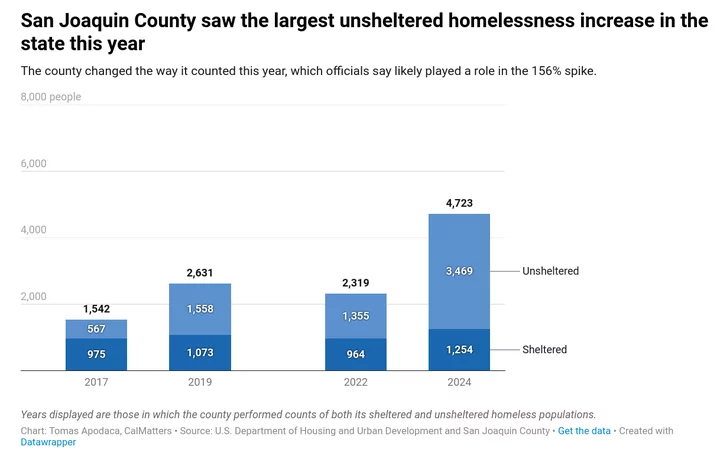

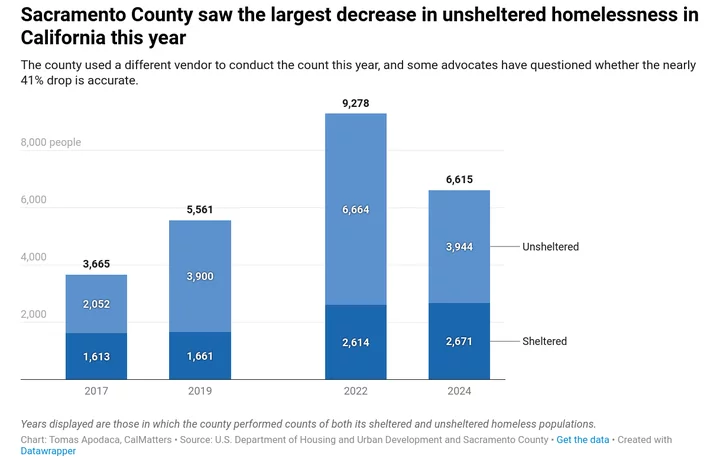

But experts warn these numbers should be taken with a grain of salt. The county that reported the biggest increase in homelessness (San Joaquin) and the one that reported the biggest decrease (Sacramento) both changed the way they counted this year – calling into question how accurately this count can be compared to prior years. And in every county, experts warn the tally is likely an undercount, as volunteers are sure to miss people sleeping tucked away out of sight.

“Ever since the (point-in-time count) became a mandate we’ve been railing against it,” said Christy Saxton, director of health, housing and homeless services for Contra Costa County. “Because it’s incredibly flawed. Everyone has a different methodology.”

Those challenges point to a bigger dilemma: Voters and politicians alike repeatedly report that homelessness is one of the most important issues facing California, but it’s hard to address the problem without knowing its full scope.

Sacramento and San Joaquin counties saw big changes. Or did they?

Homelessness doubled in San Joaquin County this year compared to the county’s last count in 2022. And the number of people sleeping outdoors — not in a shelter — increased nearly a whopping 160%. No other California county saw such a massive increase.

But the huge change raised questions.

Community leaders say the increase is, at least partially, part of a broader trend of more people landing on the streets in the Central Valley. Kern County saw the state’s second-worst increase: Overall homelessness grew 67% compared to 2022, and the number of people sleeping outside increased 128%. Fresno County didn’t count its unsheltered homeless population this year, but it saw a nearly 80% increase in overall homelessness from 2019 to 2023.

Activists in the Central Valley blame rent increases, which, unlike in big cities such as San Francisco and Los Angeles, are rarely moderated by local rent control rules.

The Rev. Nelson Rabell, a pastor in Stockton who also serves on the board of affordable housing organization Faith in the Valley, blames the recent influx of people moving to the region from the Bay Area in search of cheaper housing. Families in his congregation keep coming to him with the same story: Their landlord kicked them out and wants to remodel their home to attract Bay Area renters with more money, he said.

“They’re always on the brink,” Rabell said of those displaced families. “One check away. Someone gets sick, or you have a landlord trying to take advantage of the situation. They’re one month away from being homeless.”

But there could be another factor behind San Joaquin County’s massive increase in homelessness: A major change in the way the county counted.

This year, instead of doing the count itself, San Joaquin County used data firm Applied Survey Research, a company also used by nine other California counties this year.

“They’re

always on the brink. One check away. Someone gets sick, or you have a

landlord trying to take advantage of the situation. They’re one

month away from being homeless.”

— Rev. Nelson Rabell, board member, affordable housing organization Faith in the Valley

In a change from last year, the county also assigned volunteers to every census tract in an effort to count all homeless people. And their numbers skyrocketed.

“Knowing how many people are living unsheltered is very disheartening,” said Krista Fiser, chair of the county’s continuum of care, “but most people involved with the county feel confident that it is a significantly more accurate count.”

The new methodology likely doesn’t account for the entire increase. “Anecdotally, you can see it’s getting worse,” Fiser said.

But because of the data discrepancy, officials don’t really know how much worse.

A questionable decline in homelessness in the capital

Activists have raised similar questions in Sacramento County, which saw the state’s biggest drop in homelessness. Overall homelessness fell 29% compared to the county’s last count in 2022, and the number of people sleeping outside dropped 41%.

But Loaves & Fishes, a nonprofit that provides food and other services for homeless communities in Sacramento, says its programs served more people this year than last year. It questions whether the point-in-time count numbers are too good to be true.

“These numbers are incredibly difficult to believe and further highlight the trust issues with local government that our guests have consistently expressed over our many years of service,” the organization said in a June news release.

Like San Joaquin, Sacramento County changed the way it counted. Instead of using Sacramento State University, the county hired Simtech Solutions – a data firm that also counted for more than a dozen other California counties this year. Sacramento made the switch because officials liked the idea of being part of that broader cohort, said Trent Simmons, director of data for Sacramento Steps Forward, the nonprofit that leads the county’s count.

Simmons stands behind the reported drop. Though the vendor was different, the method they used was the same as in 2022, he said.

“When we point to a lot of other contextual data around the count, it all does point to the same direction,” he said. “We see an increase in services, we see more people housed, more shelter capacity, more permanent housing capacity, we see more funding, we see more service providers in the system.”

Problems with the homeless point-in-time count in California

The feds tell counties throughout the country to count their unhoused populations at least every two years using a point-in-time census, which generally takes place over the course of one night in January. In California, the counts generate tons of fanfare. Armies of volunteers fan out to tally every person they see sleeping in a tent or a car, and mayors, city council members and other elected officials often join in. They also count everyone spending the night in a shelter.

The results are crucial. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development uses the data to help determine how much homelessness funding to give each county. But the numbers also have come to serve as a framework around which states base their understanding of the homelessness epidemic. State and local politicians constantly reference them in speeches: Decreases allow bragging rights, and increases are lobbed as ammunition at opponents.

The data also factors into legislation. Sen. Catherine Blakespear, a Democrat from Encinitas, introduced a bill last year that would require local governments to provide enough housing for their homeless populations based on their most recent point-in-time count. While that provision is no longer on the table, the counts continue to come up time and time again in legislative hearings.

Most California counties that conducted a count this year released the results this summer. Thirteen counties, including Santa Clara, didn’t count this year – they counted last year and will count again in 2025. Another 13 counted this year but haven’t yet released their results. CalMatters compiled and analyzed the results available for each county. In reaching the statewide total, if there was no 2024 data, CalMatters used the most recent data reported to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

The feds eventually will compile the data into a national report, but that likely won’t happen until the end of the year. When it does, its total for California may be different from CalMatters’ total, because it will include data that wasn’t yet reported at the time of publication.

The federal agency recognizes the limitations of its mandatory count, saying it’s not meant to capture the “entire universe” of people who are homeless throughout the year. But, according to spokesperson Andra Higgs: “There is no other data source available that provides a more accurate count of both sheltered and unsheltered homelessness across the country.”

There are ways local officials can make their counts more accurate, such as calling people on housing waitlists to ask where they sleep, or using school data to contact families of homeless students, said Peter Connery, vice president of Applied Survey Research – a nonprofit consulting firm that conducted counts for 10 California counties this year.

But the problem, Connery said, is that most counties conduct the counts on a shoe-string budget, using staff who already have a full plate of other responsibilities. His firm charges between $50,000 and $185,000 for a count, depending on the size of the county. Those prices include paying people who are or have been homeless to help.

Counties do the best they can with what they have, Connery said.

“Does every county do an optimal job of it? I would say no, they don’t,” he said.

Did cracking down on encampments change homelessness numbers?

As officials in cities throughout California experiment with new ways to manage homelessness, they eagerly awaited the results of this year’s point-in-time count to see if their efforts paid off.

In San Diego, Mayor Todd Gloria didn’t get the reduction he was hoping for after cracking down on street encampments and directing people to “safe sleeping” sites. The number of people sleeping outside without shelter increased 6% in the city compared to last year (unlike many other California jurisdictions, the city and county of San Diego count every year instead of every other year).

San Diego banned homeless encampments across a wide swath of the city in July 2023. To give people somewhere legal to go in a city without enough shelter beds or housing, city leaders opened sanctioned camps where people sleep in tents purchased by the city, and safe parking sites for people living in RVs. The 749 people living in those sanctioned camps and parking sites are still counted as homeless and “unsheltered” by the feds, meaning they don’t help San Diego lower its unsheltered point-in-time count numbers.

Gloria called that “frustrating.” He sent the Department of Housing and Urban Development a letter this summer asking the agency to re-classify both types of sites as shelters.

“I believe the streets are better today than they were a year ago,” Gloria told CalMatters.

In the city of Los Angeles, where Mayor Karen Bass has made clearing encampments a priority, homelessness dropped 2% this year from the year before. It’s a small decline, but it’s the first time in six years the city has seen any decrease. The number of people living on the street without shelter dropped 10%.

Bass drastically changed the way the city clears encampments in December 2022, when she launched Inside Safe, a program that moves people from camps into hotel rooms. More than 2,700 people have come indoors through that program, according to LAist. But a CalMatters investigation found officials have struggled to provide the medical and mental health services participants need, and to move people from the temporary hotels into permanent housing.

“Ever

since the (point-in-time count) became a mandate we’ve been railing

against it. Because it’s incredibly flawed. Everyone has a

different methodology.”

— Christy Saxton, director of Health, Housing and Homeless Services for Contra Costa County

People living in those temporary hotel rooms are still classified as homeless by the federal government.

The number of people sleeping outdoors dropped nearly 45% in Napa County from 2022 – the biggest decrease in unsheltered homelessness of any California county. City and county officials say that’s because they’ve gone to great lengths to snap up state and federal funding.

In 2022, the county received just under $100,000 per year for permanent supportive housing from the feds, said Jennifer Palmer, the county’s director of housing and homeless services. Now, they rake in more than $400,000.

“We’re really decided that is the greatest need in the community,” Palmer said.

In two years, the county also added 95 new shelter beds, more than doubling their supply.

But in some areas of California, the funds they used to make gains against homelessness have dried up. Homelessness decreased in Santa Cruz County by nearly a quarter between 2022 and 2023. Then it plateaued this year.

The county received nearly 400 new federal housing vouchers in 2022 because of the COVID-19 pandemic. But while those have been used up, people continue to lose their homes faster than the county can pull people out of homelessness, said Robert Ratner, director of Housing for Health in the county.

“We’re not going to see progress in the (point-in-time) count if that is the continuing dynamic,” he said.

###

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

CLICK TO MANAGE