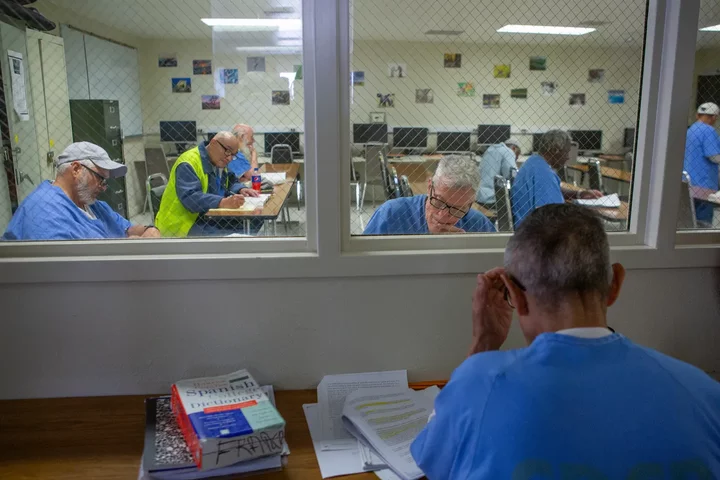

Inmates being released from California state prisons by law are supposed to receive a $200 allowance for basic necessities. A new lawsuit alleges prisons have withheld some of the money from former prisoners for years. Photo by Semantha Norris, CalMatters

John Vaesau was counting on the $200 he was entitled to by law upon leaving Folsom State Prison in June 2023, after 33 years. He was surprised when he received none of it.

“They just threw me out like a piece of garbage,” Vaesau said. “Like after all that time, it was nothing to them.”

Now, Vaesau and another formerly incarcerated person are suing the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, alleging the state agency has illegally docked fees from the so-called “gate money” that former prisoners receive to help them cover basic necessities in their initial days of freedom.

The class action lawsuit in Alameda County Superior Court estimates the corrections department has shortchanged over a million people since 1994. According to its regulations, the agency deducts money from release allowances if someone does not have dress-out clothes or arrangements for transportation.

Some, such as Vaesau, didn’t receive any money and they weren’t told why.

“I want to fight against this kind of system,” Vaesau, 49, said. “I’m hoping everybody can get what they got coming and for future people to not go through the same ordeal that I’ve gone through.”

Every year, more than 30,000 people are released from California state prisons. In recent years, the corrections department has spent about $5 million a year in gate money allowances, according to records obtained by CalMatters.

The department declined to answer questions about the funding for this story.

The lawsuit centers on a policy former Gov. Ronald Reagan signed into law 51 years ago. It states that, with some exceptions, “each prisoner upon his release shall be paid the sum of $200.”

Despite inflation, that amount has never been adjusted. In 2022, former Sen. Sydney Kamlager-Dove carried a bill to raise the gate money amount to $1,300, adjusted annually by inflation. Gov. Gavin Newsom vetoed the measure, citing its potential cost. Legislative analyses from the time estimated it would cost at least $35 million to increase the allowances.

“The gate money statute has remained essentially unchanged for half a century,” Chesa Boudin and Yaman Salahi, attorneys for the plaintiffs, wrote in court filings. “Yet rather than provide each eligible person with the $200 to which they are entitled, CDCR routinely withholds some or all of the funds based on eligibility criteria of its own making, criteria that violate the plain language of the law.”

The lawsuit, led by UC Berkeley’s Criminal Law & Justice Center and Edelson PC, seeks retroactive payments for people who were denied their gate money and an end to the department’s withholding of allowances.

The lawsuit describes the release funds as a “critical lifeline” and “small but vital aid.” According to a 2008 report by the Stanford Criminal Justice Center, the first 72 hours after someone is released from prison are paramount to the success of their long-term reentry.

“Reagan understood that the first days after release are critical to public safety so that people aren’t sleeping on the street and potentially exposing themselves to victimization, that people aren’t put in a desperate situation that might lead some to commit a crime in order to eat or to get clothes or to have a safe place to sleep,” Boudin, the former San Francisco district attorney, said in an interview with CalMatters. “When people don’t have those things, public safety suffers.”

It’s not the first time that the agency’s gate money regulations have come under fire. In 2008, the 4th District Court of Appeal held that the agency had unlawfully withheld gate money to a formerly incarcerated person under its regulations.

According to the court ruling, the regulations were “not authorized by or consistent with the terms” of the law.

But according to the new lawsuit, the 2008 ruling had little effect on others.

California lawmakers this year acknowledged that the corrections department has been making deductions from gate money allowances and approved a spending bill that would provide an additional $1.8 million for clothing and transportation.

The measure is sitting in Newsom’s desk as a part of a larger government funding bill.

Sen. Josh Becker, the Democrat from Menlo Park, who submitted their request, said he was upset when he heard about the deductions.

“This is about righting a wrong – making it clear that deductions are not to be taken out,” Becker said in an interview with CalMatters. “We feel good that with this additional money, people will get what they’re supposed to get.”

A group of advocates for formerly incarcerated people brought the funding request to Becker’s attention earlier this year. They wrote in a March 8 letter to lawmakers, “This practice has created economic harm and disadvantages among newly released individuals, leaving returning citizens significantly more vulnerable and highly susceptible to homelessness and recidivism due to unmet needs.”

The advocacy groups Root & Rebound, Initiate Justice, Legal Services for Prisoners with Children, All of Us or None and the Michelson Center for Public Policy surveyed over 70 incarcerated people returning home. They found that the corrections department deducted gate money from approximately one in three of them.

“The people who got gate money deducted were still struggling years later,” said Claudia Gonzalez, policy associate at Root & Rebound, a legal services organization in Oakland. “We have a history in California of being extremely punitive towards impoverished communities, especially indigent folks. Yet, we expect them to be successful, when in reality we’re setting them up for failure.”

###

Cayla Mihalovich is a California Local News fellow.

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

CLICK TO MANAGE