Editor’s Introduction (From the Humboldt Historian)

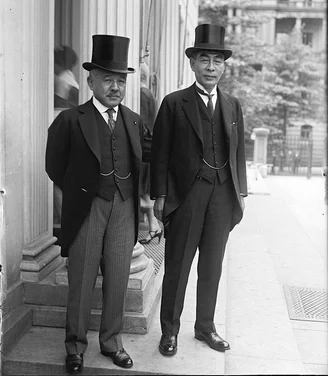

At the beginning of May 1930, the Japanese Ambassador to the United States, Katsuji Debuchi, together with his wife, set out on their first tour of our country since Debuchi had taken up his post in Washington, D.C. two years previously. The couple traveled by train from D.C. to Los Angeles. From Los Angeles, they would continue north up the coast to Vancouver, B.C., with stops in San Francisco, Portland, Seattle and Vancouver, to visit the significant Japanese communities in each of these cities.

Of course, good will celebrations were planned for them in each city. In Los Angeles on May 6, 7, and 8, the ambassador and his wife were feted by the Chamber of Commerce and the Japanese Chamber of Commerce, and while in San Francisco on May 11 through 14, Debuchi officiated at ground breaking ceremonies for the Japanese YMCA building to be erected on Buchanan Street, for which he had assisted in raising part of the funds contributed by Japan. The couple had made other stops on their way up the coast, too: they played golf at Pebble Beach and visited Stanford University. After leaving San Francisco on May 14, the Debuchis were no doubt looking forward to additional sightseeing stops as they drove through the redwoods. According to writings left by William McClure of Redway, however, the welcomes that the couple had enjoyed thus far did not await them when they entered Humboldt County. They encountered something else entirely.

Here is William McClure’s account, introduced by his daughter, Ruth McClure.

My Father, William McClure, and the Japanese Ambassador

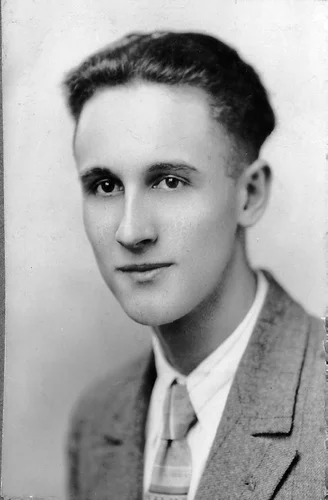

A treasure left by my father, William McClure, are his writings about his memories of Humboldt County during his early years. William was an infant when his family came to Eureka in 1911. His father operated an optical shop at 417 G Street, but the family spent their summers at their family cabin in Redway. After graduating from Eureka High in 1928, William attended Stanford University, graduating in engineering. He worked for one year on the Sweasey Dam and pipeline, then was recruited to the airline industry by United Operations, and was ultimately appointed Station Manager at Bellingham, Washington just after December 7, 1941. In 1951 he brought his family back to Humboldt, to the family home in Redway, the place of his strongest childhood memories. Both he and his wife, Elenor, loved music and they spent the next decade and a half teaching music to children in logging families.

In his later years my father wrote his memoirs. In one of these writings, he recounts an incident in Garberville involving the Japanese ambassador as he was traveling through Humboldt County in 1930.

The following is my father’s personal account of what he witnessed. He was twenty years old. It was something which troubled him all his life, and he wrote this narrative to the Redwood Record newspaper in 1982, asking for their help in finding an article he’d seen in a magazine following WWII, which stated that the Garberville incident he had witnessed as a young man was in fact one of the reasons recorded by the Japanese government for wanting to declare war on the United States.

The Narrative of William McClure, Written in 1982

The following is a story I have been going to do for about thirty-five years, about an incident that happened in Garberville.

As far as I know, no one else in the Garberville area saw the incident, and I was just standing by watching. It will be all from my memory going back about 56 years.

About the summer of 1926 — it could have been 1925 or 1927 [May 1930] — I had walked from my home in Redway to Garberville. I had gone up to the bridge and sat down to loaf. No one else was around.

Suddenly about six or seven cars came up from the direction of Eureka — the bridge was on the old highway from Eureka to San Francisco. They parked their cars to block any traffic. The men got out — about fifteen to twenty of them. They were armed with clubs, ball bats, axe handles, and guns. They stood around on the south side of the bridge waiting.

After awhile about five or six cars led by a big limousine of those days, which was a Pierce-Arrow, came from the south toward the bridge. The Eureka men stopped the northbound cars in no uncertain terms — just like a lumber camp brawl of those days. The occupants were forced to get out.

One was the Japanese Ambassador to Washington, D.C.

Now, as far as the Eureka delegation was concerned an ambassador was not any better than any other person from the Orient. Using the racial slurs of the time, they ordered him to go back. Now in this delegation with the ambassador were some American officials — I believe from the State Department in Washington. They took over the argument with the Humboldt bunch.

They gave an argument the gist of which was something like this: Washington would raise hell about this.

The end result was that the ambassador and delegation would be allowed to proceed to Portland only if the ambassador and other Japanese would not get out of the cars to eat or even to use a bathroom until they got to Del Norte County, which was at least ten to twelve hours away in those days. In fact, it took at least four and a half hours to get to Eureka. What happened en route, I do not know. I am sure no one else in Garberville saw this. I was the only one.

During the war years and for about five years afterward, I was station manager for United Airlines in Bellingham, Washington. One day a man came into my office and put a magazine in front of me and opened it to a page that was titled something like Six Reasons Why Japan Declared War on the United States. He asked, “Aren’t you from Garberville?”

Later in the day when I was not busy I read the article. When General MacArthur’s occupation men took over some or all of the files of the various government agencies they found a paper or document listing the reasons why Japan declared war on the United States. There were six or seven of them, some of which I have forgotten. But I do remember some:

- USA was spreading economic influence into Japanese area.

- USA was spreading cultural influence into Japanese area.

- USA was spreading military might into Japanese areas including Pearl Harbor, Midway Island, Wake Island, Guam, Philippines, etc.

- An incident in Garberville, California — gave date — where the Japanese Ambassador and other Japanese officials had been stopped and insulted by a bunch of American hoodlums.

As I read the last reason my memory flashed back to the scene I had witnessed. The man picked up his magazine later that day. I was going to buy a copy in town. When I got around to it a few days later, the issue had been sold out.

— William McClure, 1982

A Daughter’s Unfinished Quest

Further writings from my father indicate that years later he searched as well as he was able for the magazine with the article mentioning the Garberville incident as a reason Japan declared war on the United States, but he was not able to find it. He writes:

I hope some person interested can pursue this matter by researching magazines in the library system. I do not believe the item was in the Saturday Evening Post, but it is in some magazine. Someone get the proof. I hope this is added to the historical facts of Humboldt County.

I have searched for this article. Visiting several university libraries, I have looked in Liberty Magazine, Life, Time, Newsweek and the Saturday Evening Post. I have contacted the MacArthur Memorial Research Center, Hoover Institute, Japanese American Citizen League, Consulate General of Japan in San Francisco, the National Archives in D.C., the California State Library and have looked in several books about WWII, including those written by Gordon Prange, an authority on the war in the Pacific. I also have been unable to locate the article.

I did find references in two books to the incident my father witnessed in Garberville, in which the Japanese ambassador and his entourage were threatened by locals. The books are: California, Where the Twain Did Meet, by Anne Loftus, Macmillan, 1973, pages 177-178; and The Seven States of California, A Natural and Human History, by Philip L. Fradkin, University of California Press, 1995, page 184.

I would love to be able to locate the magazine article my father saw. This find would be a positive element to add to my father’s writings, and would be the final chapter of this story.

###

The story above is from the Winter 2013 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE