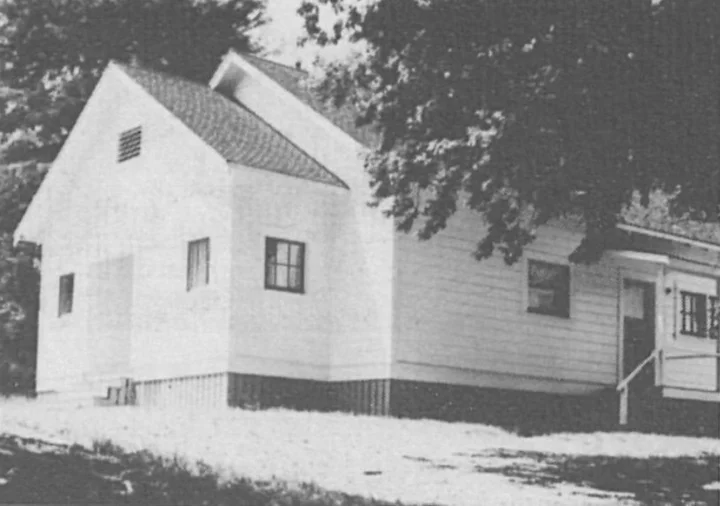

The New Mitchell School built in 1932 following destruction of the old school by fire. Photos via the Humboldt Historian.

When Ellen Sarlund gave up her first school to become Ellen Groves, the trustees of Mitchell School, just across Mad River from Blue Lake, began to look for a teacher to take her place. This was 1930 with the Depression not yet six months old. I had been applying for schools but had not thought about this isolated one. When the summer bridge to Blue Lake went out in the fall the only access to the school at West End was the gravelly road from Warren Creek.

Just prior to graduation from Humboldt State, I was informed that two school trustees were waiting to take me to the area to apply for the school at a meeting to be held that night. I was promptly excused from my afternoon practice teaching class.

The trustee who met me at the college door advised, “Don’t apply any lipstick or the trustee in the car will not vote for you. He believes schoolmarms should not be painted.”

The car was an old Model T Ford from the early 20s and the trustee in the car was a portly, aged Irishman. After leaving the Arcata area we chugged through the redwoods and along the pasture fences until we came to the home of the school clerk where I made formal application. The first trustee’s wife invited me to dinner and entertained me during the evening. I was duly accepted as teacher of the eight-grade school and then taken to my home in Samoa.

During the summer I checked out supplies in the school building and learned that I could expect students to be in grades ones, two and three, and six, seven and eight. There were adequate supplies but this school was without water and there was no means of lighting the classroom. In Samoa we burned our electric lights 24 hours a day and we had never seen a water shortage.

I soon learned that water was carried to school every day in a pail. The boys had this job and carried wood from the woodshed to the woodbox every day. We had a big dipper in the water bucket and each child brought a jelly glass to school from which to drink. A community basin served for washing hands.

Radios had been on the market for about four years, but no one in this area had one because there were no power lines. At night there was nothing to do but correct papers. All the families were in bed by 8 p.m. because they had to be up early to milk the cows before the creamery truck came. Dairying was the sole occupation. All the children knew how to milk cows.

I had never seen such a variety of spiders as the book closet contained. The building itself had three very narrow windows on each side of the classroom. All were covered with screens one-eighth inch thick to prevent breakage when the students were playing ball games.

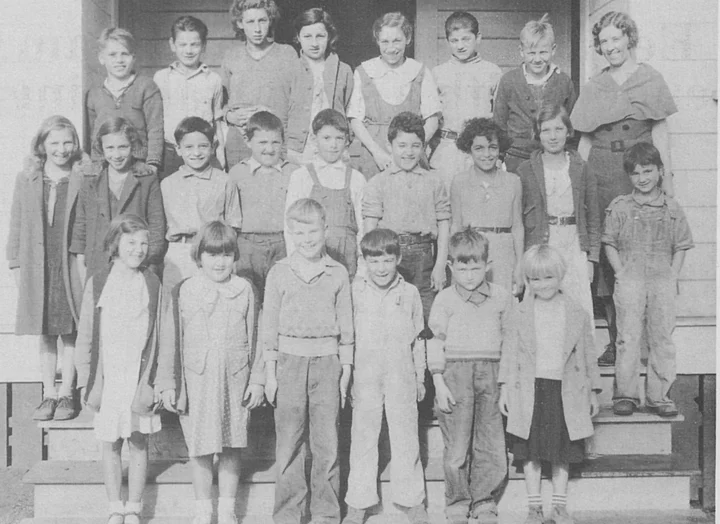

Mitchell School students of 1933-34 were, front row, left to right, Mary Nunes, Dorothy Nunes, James Moore, Americo Foglio, Leslie Christopberson, Patricia Moore. Second row, Jennie Foglio, Dorina Foglio, Gene Fusi, Antone Pegolotti, Henry Nunes, Tony Vierra, Mary Vierra, Jean Gray, Henry Fusi. Back row, Elvin Jackson, Ralph Fusi, Lucy Foglio Dolores Pegolotti, Mary Foglio, Joe Fusi, James Kane and teacher Evelyn McCormick.

School opened the first week of August with all 22 students appearing quite early to get a glimpse of the new teacher before school started. Five were first graders who seemed frightened. Their parents had informed them what could happen to them if they misbehaved. Later in the day, the older boys found a spider outdoors and placed it on my desk. I abhorred the creatures but in as calm a voice as I could muster suggested, “He doesn’t like it in here. He would rather stay outside.” Much disappointed at my reaction, they dutifully removed the creature to the outdoors.

The school district was a melting pot of European nationalities. Most of the parents had been born in Norway, Finland, Ireland, Italy and Portugal. The foreigners followed old country traditions for the most part. At school the children got along together very well unless for some reason the parents intervened.

Hearing a knock on the school door one day, I opened it to find one of the fathers. He offered me a horsewhip to use on his children. I refused it and told him I would never use a whip to punish children.

About the second week of school, children sitting along the west wall were scratching because of poison oak. Cracks in the wall permitted the vines to crawl along and unfold their beautiful leaves inside the building. I felt there was only one thing to do and that was to snip the stems and clear the wall which I did in short order. My skin was apparently immune to the oils.

A pot-bellied stove in the middle of the schoolroom burned cheerfully on cold days. In late afternoon on cloudy days, when the sun went down behind the hill, we could not see to read but I dared not close school until 4 p.m. On those days we had spelling bees or played games.

Being more than 12 miles from a barbershop during the winter was a hardship for these people. One mother sent her clippers to school telling her children they should have me cut their hair. I had done this for my family at home so I tackled the job and no one objected to the soup bowl look. Once in a while an adult came to the ranch where I lived with the trustee’s family asking me to cut hair. One of these adults was “Tiny” Abbott, who had been well-known in boxing circles. He received a terrible looking haircut but he did not complain. He was just glad to get rid of his long locks.

About once a year a so-called big goat from one of the ranches ambled down the road to the school. It was a male South American llama that had been brought into the country before the 1932 llama law was passed. In looking for a non-existent mate it smelled out his owners who were attending school. They were Tony and Mary Vierra, first and second graders. Everyone stayed inside until these tots could push the animal outside the gate and get it headed for home. Llamas are noted for their meanness at times and for their habit of spitting at their enemies.

Following my first year of school, I splurged and purchased a two-year-old Model A Ford which I used to commute to school.

At the end of this year I found real trouble. It was late April 1932. I arrived at school to find only a heap of ashes and a few rows of cement blocks. Undoubtedly an earthquake sometime before had cracked the chimney. Bystanders the night before reported the ceiling had fallen in and with no water on the premises they had no choice but to watch it burn. Nothing was saved.

With four weeks more of school before summer vacation the trustees hurriedly rented the only vacant farmhouse in the area. It had previously belonged to Milton (Tiny) Abbott and his wife, Ernestine, who had been involved in dairying for a time.

School supplies were hard to get this time of year but we managed. The Blue Lake School offered their double desks which had been used before and after the turn of the century. They had been stored in the basement. Two bedrooms became classrooms — one for the upper grades the other for the lower grades.

The county library had loaned nearly all their school books out but had a room of books from the late 1800s which they gladly shipped to us. With double desks and ancient books we had stepped back into history. Our improvised school, too, was without water and electricity. Added to this was no stove, thus no heat and only one outhouse which we shared. Nothing was important enough to interrupt school in those days. In making the transition, we missed only one school day.

We had all been looking forward to graduation day when we would have a picnic and graduation ceremonies on the river bar with all the families pre sent. Graduates this year, 1932, were Mary DeMello Brazil (now of Fortuna) and the late Walter Gray. That morning the Humboldt skies opened up for a last spring deluge.

With no let up by 11 a.m. the entire community moved into the adjoining cowbarn for games, lunch and graduation ceremonies. It was a day to remember.

Three girls had graduated the year before. All three now reside in Southern Humboldt. After 54 years, the three girls and I met as a group for the first time since 1931. They are Virginia Mell Costa of Loleta, Alva Townsend Hawkins of Ferndale, and Evelyn Kane Ingham of Pepperwood.

Following the burning of the school, Frank Kelly, county surveyor, drew plans for a new school. He had been a former resident of the area and owned a dairy ranch which he leased. With his help and adequate insurance, the new school was ready for occupancy by the last day of July. The building still stands as a private residence.

I taught two years in the old school and two years in the new school. While there I was married and the children put on a grand charivari beating their big pans and kettles with their large spoons. The older children had no trouble in transposing Miss Jones to Mrs. McCormick but the smaller children found this quite a mouthful with the result that I became Miss Cormick.

As was usual in those days, a husband’s duty was to support his wife. Unmarried young women had to fend for themselves, so after a couple of years of married life I was told that my place was at home, as I was keeping a single girl out of a job. During the Depression there were many teachers for every teaching job.

My replacement was Ruth Carroll, who later taught at Arcata High. This was her first school. Other teachers who had Mitchell as their first school were Leslie Stromberg and Ellen Groves.

During the war there was a teacher shortage and I went back into the profession in the Rolph School at Fairhaven, between the ocean and the bay on the North Peninsula, where I had a handful of students in the first six grades.

###

The story above is from the May-June 1987 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE