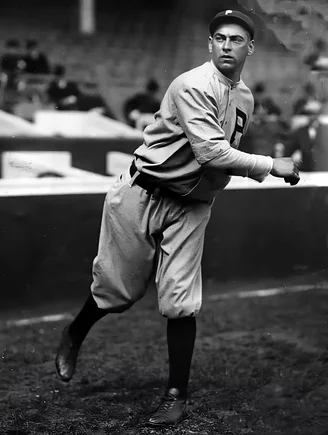

Marathon Man? Iron Man? What else would

you call Joe Oeschger (1892-1986), Humboldt

County’s first major league baseball pitcher? Consider

these facts:

- In 1917, he completed all 14 innings of a scoreless tie, pitching for the Philadelphia Phillies.

- In 1919, for the Phillies, he pitched all 20 innings of a 9-9 tie game.

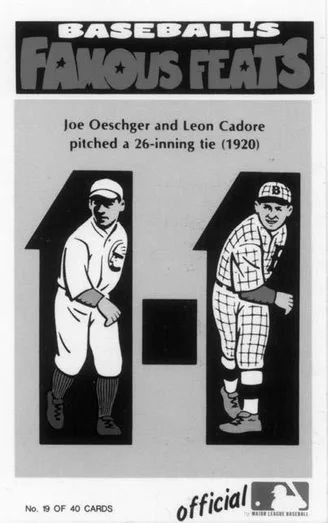

- On May 1, 1920, now with the Boston Braves, Oeschger was one of two pitchers who lasted all 26 innings in the longest game in major league baseball: a 1-1 tie between the Braves and the Brooklyn Pilots. The Brooklyn pitcher was Leon Cadore.

- All three games were ties because darkness ended the games in a time when lighted stadiums were still a dream.

Joe Oeschger gained his needed stamina for those lengthy games working on the family farm in Ferndale. The journey of the Oeschger family to the “Cream City” began in Switzerland in 1888, when sweethearts Josef Oeschger (pronounced “Esh-grr”) and Maria Michel left their homeland for Chicago on the same trans-Atlantic ship. In 1890 they married in the “Windy City” and on May 24, 1892, Joe was born. Not long after, Josef ’s sister welcomed them to Boulder Creek, near Santa Cruz. In their seven years there, two more children were born, Vernon (1894) and Ida (1897). Why the Oeschger family then chose to move to Ferndale at the turn of the 20th century is unknown, but clearly Josef had designs to become a dairyman by buying a one-hundred-acre farm on Reas Creek, off Centerville Road, and three miles from the Pacific Ocean. Once the family settled on the ranch in 1900, along came three more children: George (1901), Clara (1903), and Walter (1912).

Joe was eight years old when the family moved to Ferndale. The Oeschgers, who were Catholic, were pleased to know that the town had a grammar school run by the Sisters of Mercy, so Joe took the first of many a long walk to the school, a building that had been Ferndale’s original Catholic church. “For what we called the recess hour,” Joe reminisced years later, we had a little yard alongside the church [and] a ball we would kick around a little bit, but that was about all the education we had along the athletic line. [In class] we were not allowed to whisper or talk and really had to study. The Sisters demanded we get in our lessons or assignments and if we did not get them in, we would have to stay after school. Generally they would assign some prayers to make up for it.

Ferndale High School baseball team of 1911 from the yearbook, Tomahawk. From left, top row: unidentified, Rollin Boynton, Otto Harbers, Bob Damon, Glenn Haas, Bert Rusk. Bottom row: unidentified, Joe Hindley, Ray Goble, unidentified, and Joe Oeschger, who often had a severe look when photographed.

Joe entered Ferndale High School in 1908, and as a pitcher on the baseball team, his athletic ability blossomed. He became known countywide for his talent, and was lured into pitching for local teams sponsored by logging companies and towns. Such extracurricular activity was not approved by the county school authorities, and even though Joe was the high school’s baseball star, he was banned from pitching for his school team during his senior year.

But besides his studies and athletics, Joe found another interest, this time of the romantic type: his classmate Ivy Teal. They both graduated in 1912.

Sweethearts Joe Oeschger & Ivy Teal, 1912 Tomahawk.

That summer Joe pitched for the Ferndale team of the newly organized Redwood League, with teams also from Eureka, Arcata and Fortuna. (The league disbanded four years later.) In July, a soldier team from Fort McDowell on Angel Island in San Francisco Bay took a ship north to Humboldt County and after they played the Ferndale team, a report of the game found its way to the San Francisco Chronicle:

The Fort McDowell players bring word that Oeschger, the pitcher of the Ferndalers, is a comer. The military aggregation has played against most of the good teams in the bay section … and, in their opinion Oeschger is the monarch of them all. He is a big right-hander … and with the training he will receive at St. Mary’s College, where he is planning to attend school this fall, he expects to learn many valuable points in the art of twirling.

It was hardly unexpected that Oeschger would choose Saint Mary’s College, for the then Oakland-based institution had been supplying players to the major leagues almost one a year since 1880. While Joe entered Saint Mary’s in September for a civil engineering degree, girlfriend Ivy headed to Berkeley and the University of California. (After all, Oakland and Berkeley weren’t very far apart in those days of trolley lines.) Once on campus, Oeschger surprised everyone by choosing to also take on rugby, a sport

Saint Mary’s had several different baseball teams that played under the college name and it was the Phoenix team that featured the best players. For years Phoenix had ruled the roost of the Bay Area’s college baseball league and that year the college hired an alumnus, Eddie Burns, a fine catcher, as the baseball coach. The Oakland Tribune covered the Phoenix team’s games, and when it was announced that Oeschger would pitch against Stanford in a February 1913, game, the paper quoted Burns as saying that Oeschger “is one, if not the best, pitcher to ever enter St. Mary’s College in the past ten years, which is high praise.”

Oeschger would lose that game, but in the year ahead win more than he lost. His effectiveness as a pitcher was watched by the eastern major league clubs, and when Burns signed with the Philadelphia Phillies as a catcher in 1913, he paved the way for the Ferndaler to also sign with that team. On March 13, 1914, the Tribune reported that Oeschger “has signed with the Philadelphia National League Club and will report to the organization next week … at an annual salary of $3,000.” Joe would leave for the Phillies with less than two years completed toward the engineering degree. He would never complete the Saint Mary’s degree.

After a goodbye to Ivy, he took the train east to join the Phillies. And who would be one of Joe’s pitching partners? None other than one of the all-time baseball greats: Grover Cleveland Alexander, who in 1911, his rookie year with the Phillies, led the National League in wins with a 28-13 record. Oeschger, known as “California Joe” in Philadelphia, would not make the kind of rookie splash that Alexander had made. However, he made a good impression in his first game on April 2, 1914, when he pitched the final five innings and allowed only one hit by the then world champion Athletics. A few weeks later the Tribune wrote that Oeschger was feeling the major league pressure “having difficulty in accustoming himself to the need of quick thinking and fielding in the majors.” What resulted from the thirty-one games of his first year was a 4-8 won-lost record.

Back in Oakland that fall he would tell Ivy of one constant non-athletic problem: people’s pronunciation of his name. Reporters loved to comment on the difficulty, with one source stating that “You have to gargle to say it right. Most of the fans call it ‘Oscar,’ and let it go at that.”

The Philadelphia Phillies pitching staff of 1915, the year the Phillies won the National League title. From left: Stanwood Fulton Baumgartner, Grover Cleveland “Pete” Alexander, Austin Ben Tincup, Erskine John Mayer, Albert Wentworth Demaree, Joseph Carl Oeschger, George Watt McQuillan.

Returning in the spring to the Phillies, Oeschger found a new manager, Pat Moran, who believed the second-year player needed more seasoning, so Joe was sent to Providence in the International League for most of 1915. It was a wise move, as Oeschger developed effective pitching styles that produced a no-hitter while in Rhode Island. Moran recalled him at the end of the season in time for Joe to win one game for the Phillies as they headed to the World Series. Though they lost to the Boston Red Sox and Oeschger did not pitch in the Series, nonetheless he pocketed $830 as his share. With a little extra money, he returned home and married Ivy on November 2, 1915. They would have three children: Anne (1919), Phyllis (1923), and Joseph (1925).

Preparing for the 1916 season, Manager Moran believed Oeschger would prove both a regular and a powerful surprise in the league. Unfortunately, during spring training in St. Petersburg, a finger on Joe’s left hand was knocked out of place and cut, an injury that put him on the disabled list for most of that year. But in 1917 he rebounded with a 15-14 won-lost record and a 2.75 ERA. A hint of what was to come happened on September 4 of that year, when he pitched all fourteen innings against Brooklyn in a scoreless-tie game called due to darkness. A reinvigorated Oeschger returned to Oakland and in the off-season coached the Saint Mary’s Phoenix team that had his brother Vernon as a pitcher. (Each of his brothers attended St. Mary’s and had urgings to reach the majors, but none ever did.)

As the 1918 season began, the Phillies had great hopes for Oeschger. Gone was Grover Alexander to the Chicago Cubs, and many saw evidence that Joe could be as good. Unhappily for Joe, just the opposite happened, for at one point he had nine losses in a row! Aided by his 6-18 won-lost record, the Phillies hit the cellar. Returning home to Oakland, he and Ivy welcomed their first child, Anne.

The 1919 season didn’t start out well either, but Joe’s “iron man” side reappeared on April 30, again against Brooklyn, when he pitched for twenty innings and a 9-9 tie. Still, the Phillies manager wanted wins, not ties, so in May, Joe was traded to the New York Giants, a team managed by one of the greats: John “Little Napoleon” McGraw.

It is likely that no pitcher ever made a less impressive New York debut than Oeschger. On his first start as a Giant on May 28, McGraw sent him in as a reliever to begin the tenth inning of a 2-2 tie with Pittsburgh. Joe walked the first two batters and was pulled. (Because he put the winning runner on base, he also was given the loss!) Three days later, McGraw gave him his first start, but after watching Joe’s performance in the first inning against four hitters, the manager yanked him. Here’s what a baseball historian wrote about that fateful inning:

The Robins made four whistling hits in succession off Oeschger, but did not score a run: one man was thrown out trying to reach third, another was thrown out at the plate, and a third was thrown out stealing. “There will never be another miracle like that,” said McGraw, and shipped Oeschger to the Braves.

— Harold Kaese, Boston Braves, 1871-1953

Joe arrived in Boston in mid-August and finished off the 1919 season with a 4-2 record. After the experience with McGraw, Joe found the Braves manager George Stalling to be “a real southern gentleman” who encouraged young players, but was also superstitious and hated pigeons. (Opposing teams would toss peanuts in front of the Braves dugout to attract the hated birds.) The manager also asked Joe to keep an eye on Jim Thorpe, the roommate Stallings provided him with. Considered one of the world’s greatest athletes ever after his triumphs in the 1912 Olympics, Thorpe had turned to professional baseball with some success. The press came to know of Thorpe also because of his escapades off the field. Years later, Oeschger would recall an incident in a saloon when Thorpe chose to illustrate the new football move, the “flying tackle.” The result was that Thorpe and the patron he chose for the demonstration both flew through the saloon window and ended up outside on the sidewalk. Thorpe would finish his baseball career shortly after Oeschger’s arrival in Boston.

In the spring of 1920, Oeschger began his first full season with the Boston Braves, and on April 15 he pitched a satisfying 1-0 blanking of McGraw’s Giants, but several losses followed and people wondered whether the Braves had made another trade mistake.

Then came the historic Saturday afternoon of May 1.

The Game

The 4,500 loyal baseball fans who showed up at Braves Field in Boston that day just wanted to see a good game, but what they got was plenty more: the longest game — 26 innings — in major league history. It was the third week of the season and the Boston Braves (in lowly sixth place) were hosting the second-place Brooklyn Robins, ancestors to the Dodgers. All day it had been overcast and drizzling and rain slickers abounded. With daylight saving time now in effect, fans knew that even if the game dragged on due to a rain delay there was plenty of time to finish before night fell. (Lighted stadiums for night games didn’t arrive until fifteen years later.) They couldn’t have been more wrong.

Oeschger and Leon Cadore, the pitcher for the Robins, had already faced each other once that season. Both were highly competitive, strong athletes, each over six feet tall, and though both had been born in Chicago, each had gained their youthful strength growing up in a small Western town: Oeschger in Ferndale, Cadore in Hope, Idaho. Cadore (born November 20, 1891) attended Spokane’s Gonzaga College briefly before heading east in 1912 to pitch in the minor leagues for four years. In 1915, the Brooklyn Robins, owned by Charles Ebbets, bought him from the Wilkes-Barre Barons for $1,500. Cadore, after several winless years, finally broke loose in 1917 with a 13-13 record. The next year he was drafted into “The Great War,” but once back to Brooklyn, in 1919 he pitched a successful season of 14-12.

For the Saturday May 1 game, Manager Stallings chose Oeschger to start the game. Usually, he chose Oeschger to pitch on Sundays because he knew the Californian went to church in the morning and the manager believed in the possibility of heavenly support! But Oeschger would never pitch on a Sunday in Boston because baseball games were not permitted on the “Lord’s Day,” (the “Blue Laws”), so it was not a surprise to Joe to find out that on that Saturday he would start against Cadore.

Oeschger: “I was happy to get the starting job because Cadore was pitching and he had beaten me 1-0 in eleven innings earlier in the season. I wanted to even things.”

[The Joe Oeschger quotations are from “Joe Oeschger Remembers” and a 1970 New York Times story.]

So with the sky overcast and the field still wet for the

three o’clock “Play ball!” Oeschger and Cadore began

what the Boston Globe would call “one of the greatest

games ever played.”

Happily, the drizzle stopped at the end of the first inning and the game moved swiftly along. After four innings, it was a scoreless tie, with each pitcher having given up only three singles, scattered over different innings.

Oeschger: “Cadore had a good curve ball and I had a good live fast ball that day.”

Then came the fifth and a Brooklyn run.

Oeschger: “I blame myself for the run. I pitched too carefully to Ernie Krueger … and walked him. Then Cadore hit a double-play ball right at me. I was overanxious and juggled it. I threw him out at first, but Krueger took second. He scored on a broken-bat single.”

Though Oeschger would only give up singles in the record-length game, Cadore was hit harder: two dou bles (one by Oeschger himself) and a triple.

Oeschger: “The next inning we tied the score when Walt Cruise hit a triple against the scoreboard in left. He scored on Tony Boeckel’s single.”

The sixth inning ended with the score tied 1-1, but the seventh inning proved a breather for Joe: he got three men out with only three pitches. Sitting in the dugout, he imbibed the glass of water that manager Stallings insisted he drink after every inning.

Oeschger: “We had a chance to win in the ninth when we filled the bases with only one out, but Charley Pick hit into a double play.” without significant excitement until the seventeenth inning.

Oeschger: “The only other critical inning I had was the 17th, when [Brooklyn] filled the bases with one out. It was a great play by Hank Gowdy [the catcher] that saved my neck. Rowdy Elliott hit a comeback grounder to me and I threw home for a force on Zack Wheat. But when Gowdy threw to first to complete the double play, his throw pulled Wally Holke off the bag. He lost the ball momentarily and big Ed Knoetchy came barreling home. Holke threw to the plate and Gowdy’s spectacular diving tag nailed Knoetchy.”

On one play, the Braves had recorded two outs at home and kept the game tied! No wonder the New York Times, in reporting the game, called it “one of the most remarkable double plays ever seen.” A sports artist for the Boston Globe captured that incredible play as part of his drawing of the game.

Oeschger: “From the 18th on, Rabbit Maranville and Hank Gowdy gave me pep talks. ‘Just one more inning, Joe,’ they’d say, ‘and we’ll get a run for you.’ George Stallings, our manager, said nothing. He didn’t even ask me if I wanted to come out. If he had asked me, I would have given him an emphatic no.”

“The crowd was eminently fair,” stated the Boston Globe in its next-day reporting. “After the game had passed the eighteenth inning, each [pitcher] was impartially cheered when leaving the box or coming to bat.”

Inning by inning, the pitchers seemed to get stronger: Oeschger allowed no hits in the final nine innings while Cadore allowed none in the last six. Inning by inning, the patient fans saw baseball’s longest-game records fall: the National League’s of twenty-two innings and the American League’s of twenty-four innings.

Oeschger: “By the 26th inning the batters were squawking they couldn’t see the ball. I certainly didn’t want it to stop and I’m sure that Cadore didn’t either.”

In fact, years later, Cadore would say that if his manager had tried to take him out of the game, “I think I would have strangled him.”

But Umpire Barry McCormick did stop the game because of darkness at the end of 26 innings, though several players urged one more inning so they could tell their grandchildren that they had really played three whole games in one afternoon. Still, the umpire held his ground and the game was called with the score a 1-1 tie. The time of the game? Only 3 hours and 50 minutes! The number of pitches? Cadore guessed he had thrown “at least 300 curves,” and Oeschger some 250 pitches, mainly fastballs.

(During that same afternoon down in New York in Yankee Stadium, Babe Ruth, newly acquired from the Boston Red Sox, hit his first home run as a Yankee, one that cleared the roof of the right field stands. Ruth would ultimately hit 659 homers for the Yankees!)

For weeks after the game, the baseball commentators posited that surely the 26-inning game had harmed the arms of the two pitchers. Four months after the game, Oeschger answered the critics: “Had I injured my arm in any way I think I would have had some pain in the elbow or shoulder. I have never had a single pain. It looks to me like it’s a case of the wish being father to the thought.” In fact, in the following year, 1921, Oeschger had his best year ever in the majors with 20 wins for the Braves, including a game on September 8 against the Phillies in which he struck out three batters on nine pitches!

In the following season, Oeschger recognized that something was missing: the fastball had lost some zip and the arc of the curve had straightened out significantly. The Braves noticed it, also, and said “Goodbye” to Oeschger in 1923, while Joe and Ivy said “Hello” to daughter Phyllis. In 1924, the pitcher hung on in the major leagues with two short stints with the Giants and Phillies, but in the fall of that year, he bid adieu to major league baseball.8

With the birth of his son Joseph in 1925 and a desire to stay in the Bay Area, he contracted with several Pacific Coast League teams for a couple years, but finally called professional ball “quits” in 1927. That fall, Pop Warner, Stanford’s football coach, sought him out as an assistant athletic director and the family settled into the Palo Alto area, where Joe also was the physical education instructor for the California Military Academy. Ivy, besides being a mother, furthered a longtime interest in contract bridge, becoming a national competitor and expert.

Joe’s longing for baseball hadn’t ceased, so on summer weekends, from 1927 to 1931, he pitched for the Chico Colts of the Sacramento Valley League. Meanwhile, with dogged persistence he achieved a Bachelor of Arts degree by completing summer courses at Stanford University. On October 13, 1932 the United Press trumpeted the result across the country with the somewhat overenthusiastic headline: “Former Hurler Gets Professor Degree.”

Joe saw his future as a physical education teacher, which would give him an opportunity to share with students some of his athletic abilities and knowledge. In fact, two years earlier he had already been hired as a physical education instructor and administrator at Portola Junior High School in San Francisco. The impact he would have on youngsters would continue for twenty-seven years. The Portola district was a “working-man’s” neighborhood, a true American mix of ethnicities, heavily Jewish, Italian, and Maltese, while slowly building up in Asians and African-Americans after WWII. All family members were now solid Bay Area residents, but sadly, in December 1954, Ivy died of a heart attack.

Joe continued at Portola and two years later he married Nancy Sullivan, a history teacher at the school, an author of books on Spanish history and a “down- to-earth” woman. They both happily retired two years later and headed for the quiet life in Ferndale. There they purchased a small section of the Oeschger ranch, then being run by brother Walter, and had a house built on the hillside site, with a flagpole in front. A lane ran from Centerville road up to the home and visitors knew at a distance if the Oeschgers were available because if a flag was waving on the flagpole, they were home.

Mail was plentiful as baseball fans wrote seeking autographs while sportswriters sought interviews particularly on anniversaries of “the longest game.” In 1970, the game’s fiftieth anniversary brought special attention from sportswriters. Unfortunately, Leon Cadore had died years before in 1958, leaving Joe alone to recall that rainy day. Among the many admirers was Arthur Daley, the New York Times sports editor, who picked up the phone on May 31 and called seventy- eight-year-old Joe in Ferndale. He reported that the pitcher “came on the phone with strong and vigorous voice” and told Daley with a laugh: “I pitched many more exhausting games than that one.”

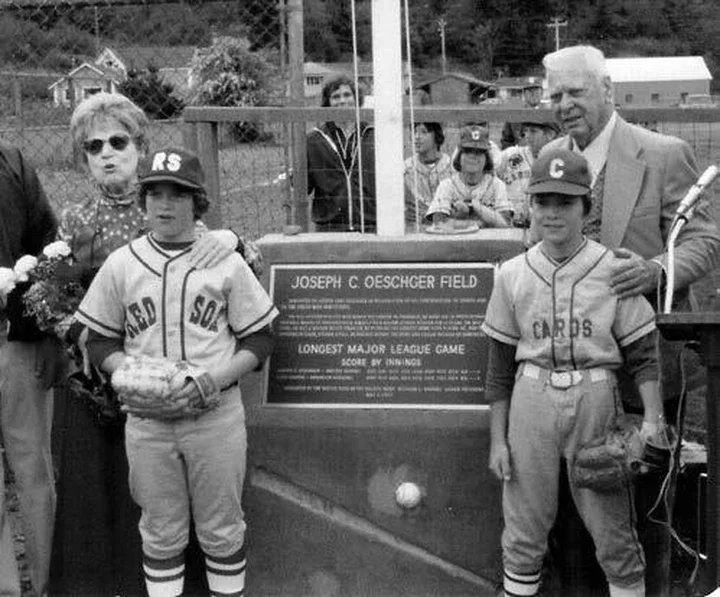

Nancy and Joe Oeschger flanking the plaque naming Oeschger Field in Fireman’s Park in Ferndale, May 1, 1977.

May of 1977 brought Joe two special honors. First, Ferndale recognized the baseball giant in their midst, and on May 1 (fifty-seven years to the day of the game) the town dedicated Joseph C. Oeschger Field in Fireman’s Park with a plaque that acknowledged his achievement and provided the game’s score by innings. A barbeque of major proportions followed for the whole town! Second, Joe was the star of “Humboldt County Days” on the weekend of May 28-29 at Candlestick Park as the San Francisco Giants played the Atlanta Braves. Sunday was “Joe Oeschger Day” and he threw out the first pitch. Nearly six hundred fans from Humboldt County were in the stands to cheer the aging pitcher.

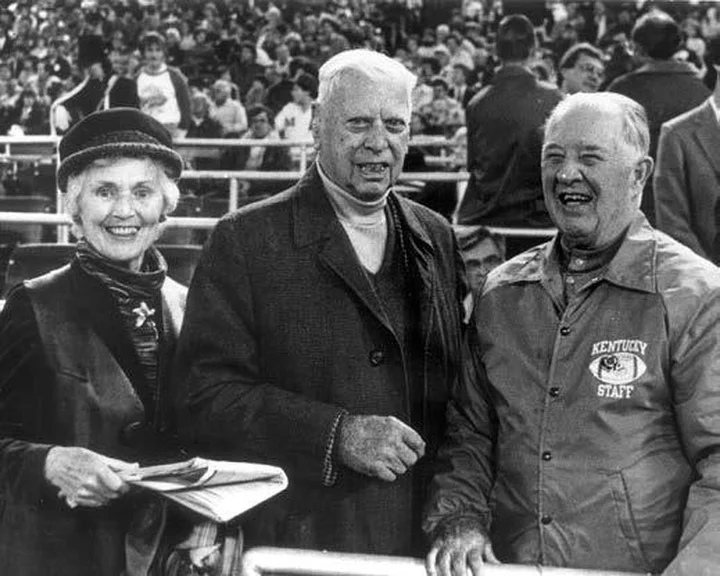

On October 14, 1983, Oeschger made his last appearance before a major league crowd. The Phillies that year were facing the Baltimore Orioles in the 1983 World Series. Since Joe was the last remaining Phillies player from the 1915 World Series, the Phillies brought him and Nancy from California so he could toss out the first pitch in one game. The 1983 Phillies had gained the name “Wheeze Kids” because of their many over-forty players, so a tongue-in-cheek Washington Post reporter wrote that the ninety-two-year-old Oeschger “looked spry in his turtleneck and threw a strike … Some in the capacity crowd in Veterans Stadium were no doubt surprised that the elderly right-hander wasn’t in the Wheeze Kids lineup.”

Nancy, Joe and Albert Benjamin “Happy” Chandler, Commissioner of Major League Baseball (1945-1951), in Philadelphia during the 1983 World Series (Phillies vs. Baltimore Orioles), when Joe, age ninety- two, threw out the opening pitch in the third game of the World Series.

But age was catching up and health issues began to surface. Joe and Nancy decided to find a small condo near her sister outside of Santa Rosa in Rohnert Park, which did make his last two years warmer and less foggy. He died of a heart attack there on July 31, 1986. Burial was in Holy Cross Catholic Cemetery in Colma, the massive cemetery that is home to dozens of former major league players with California roots. When Nancy Sullivan Oeschger died in 2006, she joined Joe in that “field of dreams.”

###

Acknowledgements

A shorter version of this article appeared in the September-October 2014 issue of Our Story, the publication of the Ferndale Museum. The author is most grateful to Our Story editor Wendy Lestina and Ferndale Museum’s Ann Roberts for all their help. Thanks also to Richard Roberts for scanning photos from the Museum collection. Joan Berry Nilsen, the niece of Joe Oeschger, provided family information. U.S. Census reports and newspaper articles retrieved through www.newspapers.com were important sources.

Two webpages from the Society of American Baseball Research (SABR) were of special help: John F. Green,“Joe Oeschger,” and Lynwood Carranco, “Joe Oeschger Remembers.” Thank you to the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library in Cooperstown, New York for photographs of Oeschger and Cadore on the mound.

###

The story above is from the Fall 2015 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE