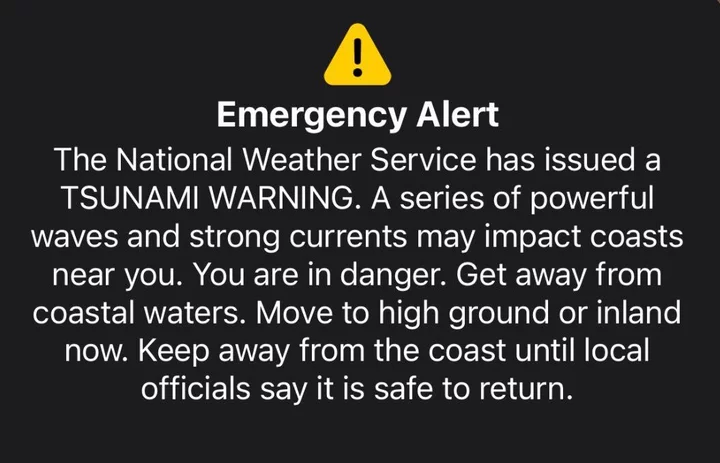

Screenshot of the tsunami warning Humboldt County residents received on Wednesday night.

###

Hours after a powerful 8.8-magnitude earthquake struck off the coast of Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula, emergency alerts sounded on phones across Humboldt County, warning coastal residents to evacuate to higher ground in response to a potential tsunami threat. The alert, issued at 8:28 p.m. on Wednesday, was the third and most urgent in a series of escalating emergency alerts.

“A series of powerful waves and strong currents may impact coasts near you,” the tsunami warning stated. “You are in danger. Get away from coastal waters. Move to high ground or inland now. Keep away from the coast until local officials say it is safe to return.”

Not long after the alert was issued, local authorities attempted to downplay the tsunami warning on social media, referring to it as an “advisory” rather than a “warning” in an apparent attempt to ease concern among anxious residents. A Facebook post from the Eureka Police Department said the tsunami warning was “sent out in error” and was “meant for Del Norte County only,” causing confusion in the comment section.

Ryan Aylward, a warning coordination meteorologist with the National Weather Service (NWS) office in Eureka, told the Outpost that the alert was issued intentionally, but said at no point were local officials expecting inundation outside of the tidal zone.

“Honestly, it was confusing for us too because we didn’t know where exactly the threat was,” Aylward said in a recent phone interview. “We knew that the tsunami wave height for Humboldt Bay was going to be about a foot, so we weren’t expecting waves to exceed the normal tidal area. But, after the warning went out, we talked to the local Office of Emergency Services, and they wanted to emphasize in the messaging that Humboldt County is not in a dangerous situation and people don’t need to evacuate, but they should avoid beachfronts and harbors.”

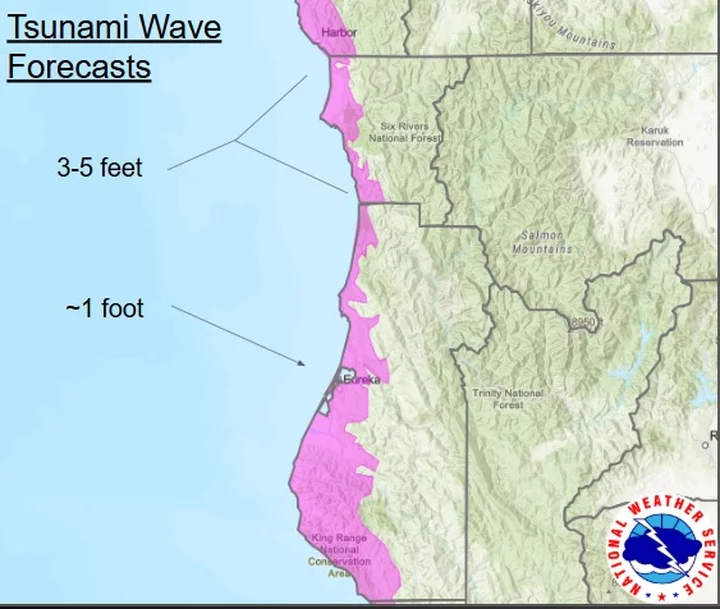

As predicted, the tsunami that arrived at our shores just before midnight was measured at about 1.2 feet — well within the threshold for a tsunami advisory — with no reported damage to the Humboldt Bay area. Our neighbors up in Crescent City didn’t fare so well, with local officials reporting up to $1 million in damages after three- to four-foot waves battered the city’s harbor.

Understanding the Tsunami Warning System

When an earthquake strikes, staff at the National Tsunami Warning Center (NTWC) in Alaska rapidly analyze seismic data to determine whether or not a tsunami is possible and, if so, when and where it will occur.

“They’re trying to analyze what type of earthquake it was, how deep it was and trying to get that exact magnitude to understand the tsunami threat,” Aylward explained. “Once they have an idea of the magnitude and have confirmation that the earthquake generated a tsunami, the [NTWC] analyzes data from the buoys out in the ocean and creates a model to determine the approximate wave height forecast for the West Coast.”

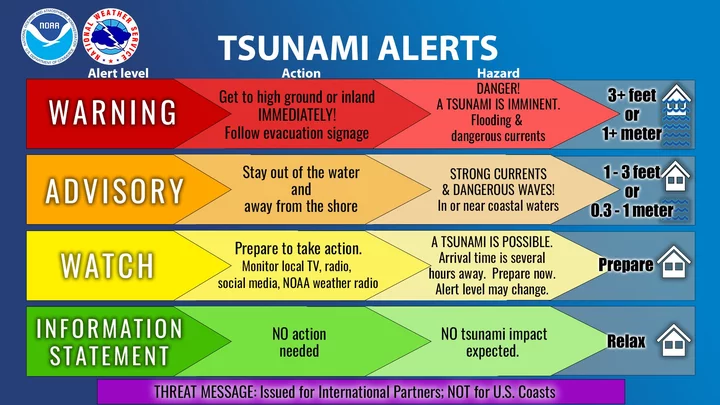

Graphic: National Tsunami Warning Center

As more data comes in, the NTWC runs the model again and again to get a better estimate of the wave size and the duration of the tsunami. They also look at the region’s history of tsunamis. In this case, staff determined the tsunami would exceed the warning threshold for several “small pockets” on the North Coast.

“They made the decision [to issue] a tsunami warning for Crescent City — that wasn’t even a question — but they decided to pull [it] as far south as Cape Mendocino … because of a spot right around Trinidad that was [expected to] exceed the threshold, which is just over three feet,” Aylward continued. “For most areas in Humboldt County, it was advisory, but there were some small pockets — like that spot up near Trinidad and other remote areas up in northern Humboldt — that could exceed the threshold. So, that’s how we ended up with a warning.”

In the hours leading up to the tsunami’s arrival time, the NTWC held hourly briefings with local and state authorities, including the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services (OES) and Humboldt OES, the California Geological Survey and NWS. If waves aren’t expected to exceed the advisory threshold, local jurisdictions are empowered to make their own decisions on which areas of the county are notified, said Humboldt OES Program Manager Ryan Derby. However, that process changes when a tsunami alert is upgraded to a warning.

“In those cases, the NTWC issues Wireless Emergency Alerts (WEAs) to jurisdictions within the tsunami warning scope, without prior notification to the impacted jurisdiction,” Derby wrote via email. “Their ability to issue WEAs is at a countywide level, which prevents their ability to notify smaller subsets of a county. This results in the entire county receiving WEAs from the NTWC when only a small portion of the county may experience warning-level impacts.”

It’s a delicate balance. While it’s generally best to err on the side of caution, an emergency alert urging residents to evacuate immediately can incite panic and chaos. Remember that 7.0-magnitude earthquake we had last December? Before the shaking had even stopped, a siren-like tsunami warning emitted from our phones, prompting hundreds — perhaps thousands — of Humboldt County residents to evacuate their homes and offices, gridlocking traffic on Highway 101 and the Samoa Bridge.

After the disorganized response, Humboldt OES, in partnership with the Eureka NWS and the Redwood Coast Tsunami Work Group, held a countywide tsunami evacuation drill to practice proper evacuation procedures. Still, comprehensive education around disaster preparedness is lacking.

‘One Size Doesn’t Fit All’

Reflecting on this week’s emergency response, Derby emphasized that every incident is different, particularly when it comes to earthquakes and tsunamis. That’s why it’s so important for residents to familiarize themselves with the tsunami hazard map — linked here — and to listen to guidance from local emergency officials.

“The main takeaway is that for near or local earthquakes, when strong and/or long-duration shaking occurs, the earthquake is the community’s warning,” he said. “We must treat every tsunami advisory and/or warning seriously and trust the guidance of local officials until an ‘all-clear’ message is provided. Complacency to these situations can result in truly devastating impacts to the community and people’s lives.”

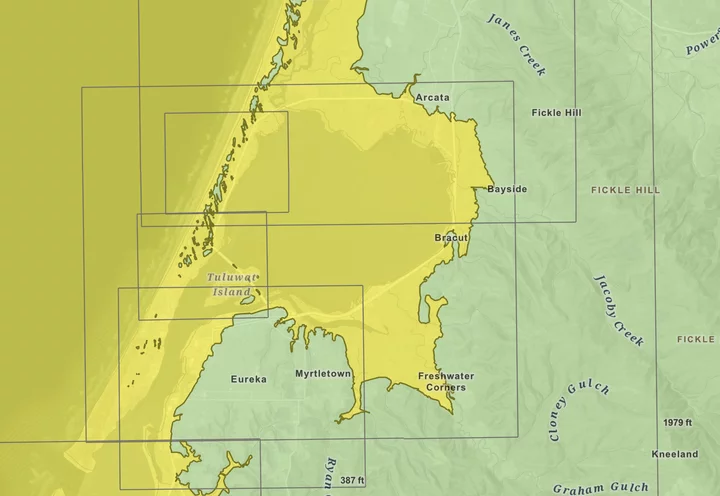

Still, there’s room for improvement, he said. Take the NTWC and NWS mapping system, for example. The map below, which was used in several advisories and warnings issued by the NWS, depicts the weather forecast zone for the Humboldt County coast, not the tsunami hazard zone.

Image via Eureka NWS

“While the NTWC alerts and their automated process are in place to provide for public safety, and community members should absolutely pay attention to those alerts, the best advice we can provide is to follow the guidance and direction of local emergency officials,” Derby said. “Local emergency information takes into account the nuances of our specific threat landscape, community makeup and emergency actions that residents and visitors should take.”

Lori Dengler, emeritus professor of geology at Cal Poly Humboldt, agreed, adding that emergency officials “need to do a better job of identifying and forecasting impacts.” She also suggested that the NTWC and NWS implement tiers for different levels of tsunami warnings.

“One size doesn’t fit all,” Dengler told the Outpost. “Right now, we only have one level of tsunami warning — anything between three feet and over 100 feet. Our tsunami maps are based on our worst-case threat — an earthquake the size of Kamchatka or the 2011 Japan quake happening right here. … But most tsunamis are far smaller than this and we need to follow Japan’s lead and have two or three levels of tsunami warning: moderate, large, enormous. That way, we could be more precise in describing the areas likely to be impacted.”

Dengler also suggested that the NTWC and NWS change the terminology for tsunami alerts because residents might not know the difference between a watch, advisory and warning. “[P]eople need to know what to do on their own.”

Aylward said the NWS office is working to improve and refine the local mapping system and reduce the scale of the emergency alert system.

“Currently, the wireless emergency alert system goes out to the entire county [when there is a tsunami alert],” he said. “People out in Hoopa received it even though, of course, there was no tsunami danger out there. We’re trying to narrow the [alert] area.”

###

Not sure if your house is located in the tsunami zone? Check out the state’s interactive Tsunami Hazard Area Map at this link.

Additional tsunami safety resources

- Redwood Coast Tsunami Work Group

- Humboldt Emergency/Disaster Information

- Humboldt Alert Sign-Up

- Arcata Emergency Preparedness

- USGS Earthquake Hazards Program

- CalOES Resources

- California Earthquake Authority

- NOAA Tsunami Safety

###

Do you know your zone? (Tsunami zone depicted in yellow.) | Screenshot of the Tsunami Hazard Area Map.

[NOTE: This post has been updated to include additional safety resources.]

CLICK TO MANAGE