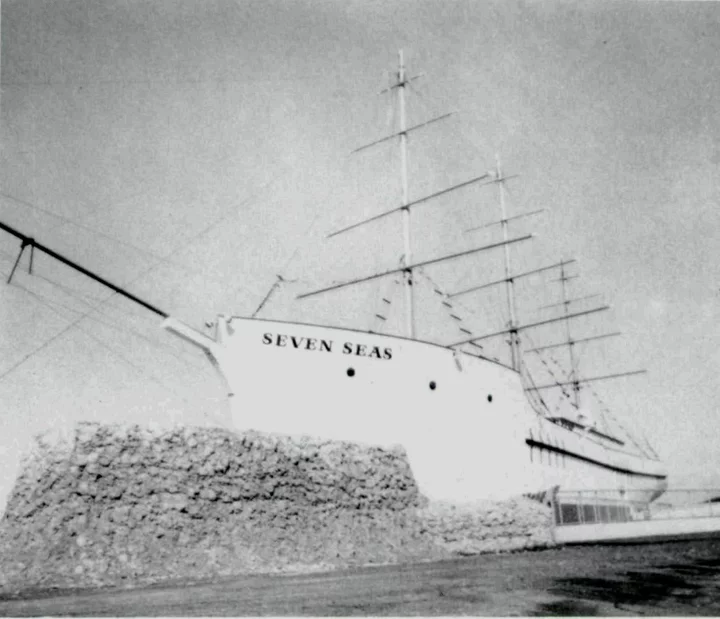

The “Shipwreck” Seven Seas measured 30 feet wide by 200 feet long; bottom, these items were among the many featured in the Shipwreck Museum, c. 1970. Photo via the Humboldt Historian.

After 28 years of existence, at 5 a.m. on April 12, 1989, a fire brought the end to a project a man and his friends had put an enormous amount of time, money and energy into, hoping it would be a successful enterprise.

Sometime during 1960, Jim Turk sat idle after breakfast one morning. While doodling with a pencil on a piece of paper, he made a drawing of a ship. He loved ships and, in the past, had made many models. An idea came to him: It would be a wonderful tourist attraction to have a ship here on land that people could visit. The idea was well suited to Humboldt Bay, as there had been many wooden ships built here. He was also convinced that there should be fish on display along with this ship, as the bay was also a great fishing port.

He explained his idea to a friend, Mel Pinkham, who in turn brought in Lamone Call. Both thought their friend Jim had come up with a great idea. This ship was to be a tourist attraction, complete with coffee shop, gift shop, museum, aquarium and seal pool.

They talked to Ben McWhorter and Harold Barnard of Hollander’s Jewelry, both of whom went along with the idea. The men held several meetings and decided to go ahead with the project. As an initial step, they incorporated as “Shipwreck Incorporated.” To finance it, they each put up $25,000 for starters. Jim Turk was named general manager and was given a share as promoters stock, a fair enough move considering as the whole thing was his idea.

Lamone Call and Chauncey Gould owned land near King Salmon which they sold to the men. The 11 acres went for $1,500 each and were considered an ideal location.

Map by Andrew Goff.

They hired local architect Bill Van Fleet to make some sketches. They also brought in a fine building contractor, Ole Antonsen, to design and build this “ship” which had been wrecked. It measured 30 feet wide by 200 feet long and required that very heavy floating concrete foundation be poured. Actual building of the project began in the early part of 1961. The men contacted a good plumbing contractor, Calvin Wilson, to do all the necessary pipe work—a complicated and very big job. Chester The North Pacific octopus greeted visitors to the sight of the “Shipwreck.” Brown was hired to take care of the electrical part of this job, and the firm of Dunbar and Batich agreed to do the painting. These contractors were very good at their trades and were well established in the community, having enjoyed excellent reputations through the years.

Jim Turk and Calvin Wilson, the plumber, traveled from Seattle, Wash., to San Diego, Calif., to visit every known aquarium or similar business. Harold Barnard visited the San Diego Zoo, in an effort to learn the proper way to install the necessary piping, pumps and tanks they might need. He also studied the proper materials needed to handle the amount of salt sea water required for this building project (salt water is very corrosive and must be kept at just the right temperature, making it very difficult to handle). The sea water had to be run through filters, which had to be cleaned regularly—no small job. The fiberglass fish tanks were custom-made in Vancouver, Wash. The glass in front of the fish tanks was made special for this purpose—extra strong, very expensive. The 10 fish tanks, each holding 750 gallons of sea water, required a total of 7,500 gallons of sea water to be run through the filters every day.

The restaurant was located on the top deck, thereby offering a view of Humboldt Bay. The gift shop and viewing area for the aquarium were below deck, while the restrooms were in the stern of the ship, below deck.

After several months work, the ship was finally ready for masts and rigging. The team hired Humboldt Gates to design and install this partof the job, and a wonderful job he did. Three tall masts were installed in the ship, each with four cross-arms made of aluminum pipes. The long mast was located near the deck, while the remaining graduated to shorter lengths. At one time replicas of sails were hoisted along with flags, painting a very pretty picture on Humboldt Bay.

In the front of the ship, in what resembled a large rock, supplies were kept. A building in the rear housed all the pumps, filters and other machinery needed to operate this facility. Turk purchased a mobile home for his personal living quarters and parked it on the bay side of the ship. His father-in-law, Charles Barrows, also lived and worked at the site.

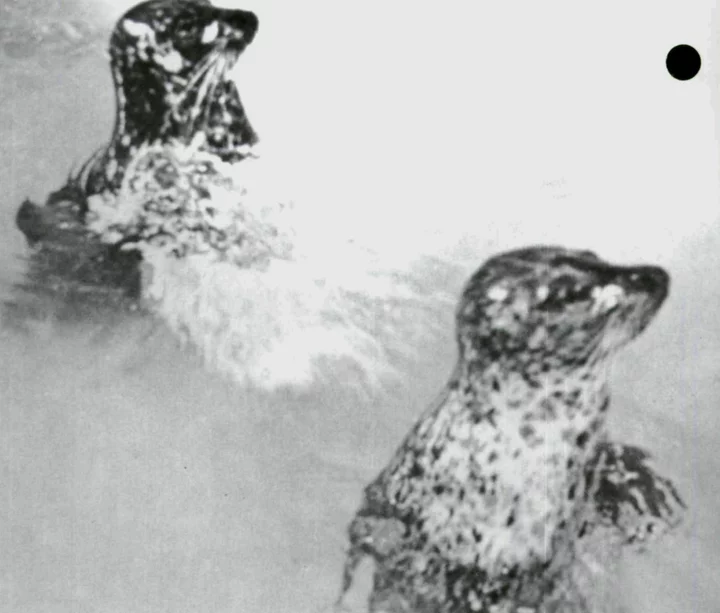

The seals played in the seal pond and proved to be the most popular attraction. Photo via the Humboldt Historian.

The seal ponds were located in front of the ship, complete with walks for tourists to watch and feed the playful seals. The seals proved to be one of the best attractions, as everyone loved to watch the playful creatures.

The seal pond was about 80 feet long by 12 feet wide. It ran seven feet deep on one end, tapering up to the other. The pool held 10,000 gallons of sea water and was called Pirate’s Cove. Children loved rowing about in a small row boat in the “cove.”

Ben McWhorter, an experienced pilot with his own airplane, along with Jim Turk, flew along the coast and found a seal rookery north of Fort Bragg. The rookery was located about five miles north of Rockport, at Usai in Mendocino County. The two men then rented a fishing boat as well as the services of two skin-divers. The divers went on the beach where the seals were, captured a few young seal pups and put them into sacks. The pups were brought “home” to the Shipwreck, where they were placed in the seal pond and provided with good care and plenty of food. The seal pond was always of great interest to the Top, public.

It was soon found that a great many seals were making their home right here in Humboldt Bay. Eventually, most of the seal pups were captured in south Humboldt Bay with the use of nets. These young seals were kept in a fenced area adjoining the Shipwreck where they were fed several times a day and given vitamins to keep them in good health. Many people wanted to purchase a seal or two, which led to a very profitable business for Jim Turk. He did come to capture and sell seals to many zoos and aquariums around the country.

The octopus, a very touchy and difficult animal to keep even under the right water conditions, also lived at the Shipwreck. This particular octopus was reputed to be one of the largest in captivity with a 19-foot span. Likewise, there, were many different fish that had to be provided with just the right food and proper care as Shipwreck residents.

The large parking area out in front was graded and graveled, in fine shape with room for 100 cars.

When the Shipwreck was completed, at a cost of approximately $250,000, the ship gleamed white with brown trim. Christened the Seven Seas, a grand opening was held in September 1961.

About the time the project was completed, the California Dept. of Transportation (Cal-Trans) decided to work on Highway 101 for several weeks, right in front of the Shipwreck; this did not help with the opening. However, the Shipwreck apparently took off and, during one of the first years, 90,000 people registered in attendance.

During its heyday there were some 20 full- and part-time employees, many of whom were students who wanted to learn something of this work and needed a part-time job.

During 1969, Lady Bird Johnson came up with a bill to remove all signs along the highways that were placed there after 1960. This action put a damper on attendance at the Shipwreck, as 38 of the signs had to be removed from Cloverdale in the south, to Crescent City in the north. As soon as signs were removed, attendance fell off drastically because tourists could not notice the Shipwreck without the signs to indicate its location. In the early part of 1971, Gary Barnard painted the exterior of the ship a bright yellow, in hopes of attracting tourists.

In 1972, the owners decided to close the Shipwreck for a time until they could decide what to do about rising costs. With no one there to look out for it, the Shipwreck became a haven for transients and teenagers who covered the walls with graffiti. Vandals soon moved in, breaking into the buildings, chopping holes in the roof, breaking the glass, tearing down the rigging, stealing fixtures and fittings, sleeping on the premises and building fires. The Fire Department was called to the scene many times. The weeds grew, the wind, sun and rain did their work and the place, in general, seemed to fall apart.

Then came the final day: April 12, 1989 …

###

The story above was originally printed in the September-October 1993 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

###

[Ed. — The photo gallery below, by the Outpost’s Andrew Goff, shows you what remains of Shipwreck today.]

CLICK TO MANAGE