The Buhne Mansion (left) and David Evans’ home (right) were among several Victorian-era structures that were demolished in Eureka in the mid-20th century. | Photo: Eureka Heritage Society

###

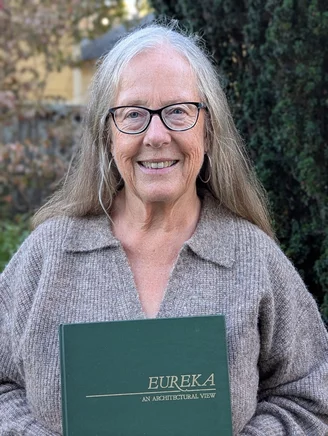

If you’ve lived in Eureka for any length of time, you’ve surely come across a copy of “Eureka: An Architectural View,” often referred to simply as “The Green Book.”

Published by the Eureka Heritage Society in 1987, “The Green Book” is an extensive inventory of approximately 1,600 “architecturally significant structures,” nearly half of which are listed on the city’s Register of Historic Places. The book features black-and-white photographs of 1,200 historic structures — ranging from Victorian-era mansions and Craftsman-style bungalows to Classical Revival commercial buildings — that date back to the 1860s. It is a truly remarkable work.

But how did “The Green Book” come to be?

###

During a recent talk at the Humboldt County Library, sponsored by Uplift Eureka, Mary Ann McCulloch of the Eureka Heritage Society went over the extensive history of “The Green Book,” which was born out of a local effort to stop the demolition of historic buildings in the 1960s.

In the 1950s, during the post-World War II economic boom, the United States rapidly expanded its housing stock to accommodate tens of thousands of returning veterans, many of whom chose to abandon city life for new suburban developments that were more cost-effective for growing families.

“The unparalleled surge in demand for housing … was a boon to the area’s lumber industry,” according to “The Green Book.” “While the scope of commercial architecture in Eureka was somewhat limited in the post-war years, the city’s residential areas continued to expand and develop, reflecting the preference for the suburban lifestyle that embodied the changing social structures and attitudes of the period.”

It was around this time that the demolitions began.

“Many people felt that the Victorians in post-war Eureka were too large, too ugly and too hard to care for,” McCulloch explained at Wednesday night’s talk, prompting groans from the audience of 40-plus local history enthusiasts. “They just didn’t fit the style of the day, and so that a lot of them were either demolished or modernized.”

Several Victorian-era mansions were demolished in the 1950s, including the Buhne Mansion, Huntoon House and Porter House. McCulloch flipped to a sepia-toned photograph of the Sumner Charles and Amelia Carson home, located at the corner of Sixth and J streets. The Colonial Revival home, built in 1914, was demolished in the 1960s to make way for the Times-Standard building.

The Sumner Charles and Amelia Carson home, formerly located at 930 Sixth Street in Eureka. | Photo: Eureka Heritage Society

“Before they demolished it, they allowed the community to tour it, and I begged my father to buy the house. Unfortunately, it had already been sold. I don’t think he would have bought it anyway. I was spoiled to a point, but not that spoiled,” McCulloch laughed. “It was a fabulous house, and to have it gone — well, what can I say?”

The “out with the old, in with the new” approach inspired several local people to take action, including Ray and Dolores Vellutini, Bob and Barbara Maxon and Norton Steenfott, who bought up old buildings along Eureka’s waterfront. “They believed wholeheartedly in saving Old Town,” McCulloch said.

This effort led to the formation of the Eureka Heritage Society, which was established in 1973. Shortly thereafter, the organization launched a citywide survey — led by Dolores Vellutini, Sally Christensen, Muriel Dinsmore and Ted Loring Jr. — of more than 10,000 structures, including not only private homes and commercial buildings, but also garages, carriage houses, water towers and other outbuildings.

“When Dolores agreed to take on the task of heading up the survey, she didn’t realize she was undertaking the most extensive survey of historic structures in California at that time,” McCulloch said. “The ultimate goal was to plan for the preservation of Eureka’s heritage, know the locations, problems and potentials of the city’s outstanding structures and neighborhoods, the forces that were making some structures deteriorate, and gain insight into how to stop and reverse the deterioration.”

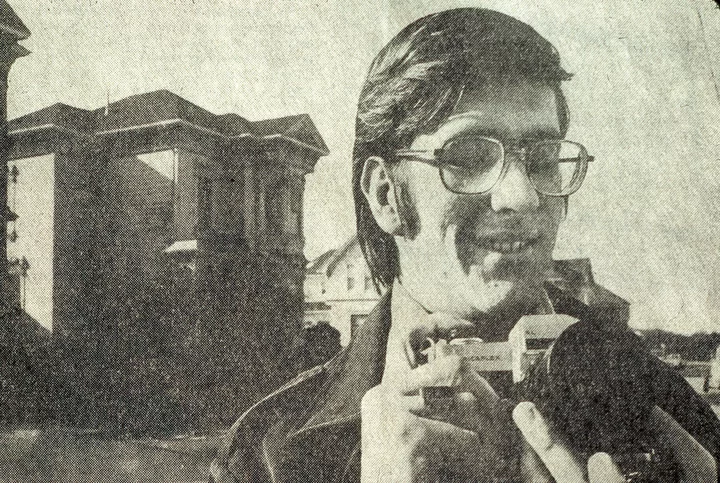

Milton Phegley conducting survey work in the early 1970s. | Photo: The Times-Standard via Eureka Heritage Society archives.

Milton Phegley became the de facto leader of the group of 30-plus volunteers sent to photograph the 10,000-odd structures. Speaking at Wednesday’s talk, Phegley admitted he didn’t fully realize the scale of the project.

“I’d come to find out maybe a couple years later that I raised my hand too high and too fast,” he laughed. “We provided the leadership for it — prepared the survey sheets, loaded and processed the film and made the little contact sheet prints that went on the survey cards.” (Those original survey cards — including those that were not published in “The Green Book” — can be viewed in the Humboldt Room of the library.)

After wrapping up his bit of the surveying work, Phegley left for San Diego for graduate school in 1975, where he would go on to study geography and city planning. While he didn’t have a hand in putting together “The Green Book,” he said the surveying experience proved to be a good exercise for his future career in planning.

Volunteers would spend another decade poring over the survey results, researching the history of each building and subjecting it to the same criteria used by the National Register of Historic Places, with the hope that those selected would one day be eligible for nomination. The Eureka Heritage Society worked with a San Francisco-based architecture firm to help edit and organize the information for publication.

All told, production of “The Green Book” would take 12 years to complete. “This book, we hope, will stand as a testimony to the uncommonly rich architectural heritage of our city, as well as to the dedication, enthusiasm, and talent of all those who contributed to its realization,” Vellutini wrote in the book’s introduction.

Over the years, McCulloch said the heritage society has considered resurveying some of Eureka’s neighborhoods or updating “The Green Book” in some form to include buildings that weren’t considered historic at the time of its publication. Unfortunately, the money isn’t really there.

“Today, historical surveys can cost upwards to over $1 million,” she said. “Perhaps someday we’ll get $3 million or $5 million, and then we’ll be able to do a whole ‘nother survey again. But until then, this remains as a snapshot of what Eureka was like in the mid-70s.”

More information on “The Green Book” can be found at this link. You can also find an interactive map of Eureka’s historic homes, complete with photos and descriptions, here.

Many of Eureka’s Victorians are still standing, including the Simpson-Vance House at 904 G Street. | Photo: Eureka Heritage Society.

CLICK TO MANAGE