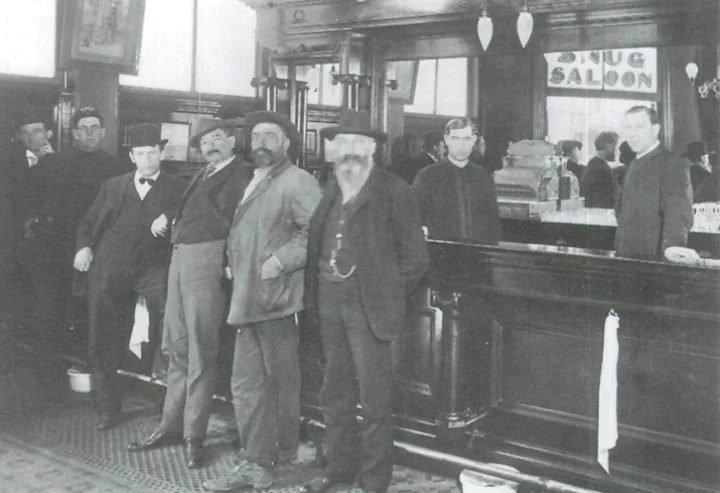

The Snug Saloon, located next to Snug Alley just up F Street, was a popular spot in Eureka. Pictured in this 1901 photo are (from left) Casey Fulmore, unknown, Jimmy Fox, unknown, Sam Dowling, Dan Hallaron, Bob McGaraghan, and Bill Bryan. Photo via the Humboldt Historian.

###

Sunset and evening star,

And one clear call for me!

And may there be no moaning of the bar

When I put out to sea.

— Tennyson

###

The bar that Tennyson wrote of was metaphorical, but habitués of early day Humboldt Bay had a multiplicity of bars they could encounter that were all real and all — at least occasionally — dangerous.

Those that threatened Humboldters most frequently were not on the high seas, but in Eureka’s Old Town, where bars of the bibulous variety spelled peril for both the unwary and for those who sought it. Loggers were the biggest seekers, arriving Saturday nights on the “Whiskey Specials” — logging trains that took the “freshly scrubbed, beargreased” woodsmen from their worksites in the tall timber to First Street, depositing them by the tracks like so many loads of freshly felled redwood. From there, the intemperate pleasure seekers made their way saloonward, some faltering at the Fairwind, comer of First and F, or at the Snug, which snuggled next to Snug Alley just up F Street.

Those with greater capacity or determination managed to stroll or stagger all the way to Second Street — the “Deuce” — where liquor dispensaries like the Louvre waylaid most of the rest. The Louvre, now respectably reincarnated as a rare and used bookstore [Eureka Books — Ed.], used its architecture to entice the clientele to purchase more than drinks. The second-story balcony, still present, was situated in such a way that when a libation-minded logger tilted back his first schooner of beer, his line of sight would rise to just the angle necessary to view an enticing bit of ankle displayed above him by one of the Louvre’s lubricious ladies, thus alerting him there were more satisfactions available than that of merely quenching his thirst.

Some saloon patrons chose less costly pursuits, of which the barroom brawl was the most frequent. Here the aim was to avoid catching a case of “loggers’ smallpox,” the frequently found facial scarring caused not by a virus, but by the punctures that resulted from a stomping inflicted by an opponent wearing calk boots. Another pastime was attempting to stride atop the bar counter from end to end while equipped with such spike-soled footwear, as both bystanders and the barkeep tried (often with success) to knock the contestant to the floor.

A 1909 survey counted sixty-five saloons in Eureka, their corrupting effects abetted by thirty-two “houses of shame.” The bar tally had dropped to fifty-three in 1916, and it officially fell to zero three years later, with the start of Prohibition. Alcohol was still available along the Deuce, of course, but now it was found only in back rooms or behind closed doors.

It was not until April of 1933 that the suds flowed freely again. Barely had the shot glasses been broken out before shots of a different sort disquieted the Louvre. Its co-owners, Fred Carter and Tom Slaughter, had been bickering about the business for some time, when, on the evening of June 3, they commenced arguing in the Louvre’s lavatory. A pair of shots rang out and Slaughter ran for the back door. Carter, hard hit, fired a bullet at his fleeing associate; it missed and struck the door casing instead. Carter then staggered out into Opera Alley, where he shot once again at Slaughter as he dashed into the adjacent High Lead’s rear entrance. Carter then made his way back into the Louvre, to be attended by the bartender, C. L. Hoffman, as he died.

Slaughter’s subsequent trial was front-page news as his attorney called thirty-eight witnesses to prove that he’d perforated his partner in self-defense, while the prosecution placed most of its money on a single star witness, William Samuels, who was in the alley at the time of the shootout. Samuels’ effectiveness, however, was limited by his being blind, and, after some eight hours of deliberation, the jury failed to find Slaughter, despite his name, guilty of even manslaughter.

A block up Second Street, the Oberon Saloon seldom saw such unseemly behavior. An “exclusive” establishment that always offered an assortment of cold cuts to its patrician patrons, it attracted Jack London one evening in June of 1911, when the novelist was traveling up the coast.

Also attending the Oberon that night happened to be Pat Murphy, a strapping young college grad who’d come west to see his brother, Stanwood Murphy Sr., the president of the Pacific Lumber Company. Murphy and London began to talk. It soon became apparent that Pat, the ultraconservative Republican brother of a leading local lumber baron, found little to agree with in the pronouncements of one of the country’s most passionate proponents of Socialism. Seeing trouble brewing, attorney H. L. Ricks attempted to persuade Murphy to leave. His entreaties were disregarded.

Murphy later indicated that he had never started a fight in his life but had also never run from one once it started.

He didn’t run now when London, apparently deciding the fist was mightier than either pen or sword, punched him. Murphy not only stood his ground, but also eventually landed a solid left that briefly dropped London to the floor. The author subsequently departed Eureka with a better reputation for his writing than his right hooks.

###

The story above was excerpted from the Spring 2000 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE