February

26, 2025 marks the 165th anniversary of the 1860 Wiyot Massacre. The

event remains one of the most appalling mass-casualty incidents in

California history and stands as a permanent scar on Humboldt

County’s collective memory. Where traditional narratives of the

massacre have centered around settler-colonial perspectives, it is

important to remember this event with emphasis on the experiences of

Wiyot victims. Essential to this perspective are the Wiyot

History Papers,

a collection of documents published and digitized through Cal Poly

Humboldt Digital Commons — they are a collection that everyone

should read. One of the testimonies included in these papers was by

Jane Sam, a 15-year-old Wiyot survivor.

During the last week of February 1860, Wiyot people across Humboldt converged at Tuluwat Island for the World Renewal Ceremony.1 This long-held tradition anticipated the continued prosperity of the world. Days of jump dancing were hosted in honor of the Creator to bring balance back into the world. In 1860, revelers may have prayed for an end to the settler-indigenous conflict that had consumed the area for a decade.2 Moreover, the World Renewal Ceremony served as a community gathering of the Wiyot — people traveled from around Humboldt Bay, Eel River, and Mad River to visit the island; even some Yurok were in attendance.3 The ceremony was also a period of reunion with distant families. Some took the opportunity to make new friends, share gathering methods, and play celebratory games. After several days of intense celebration, the renewal ceremony finally came to a close.4 Jane Sam, a Tuluwat survivor, was there the night before the horrific massacre:

The dance was 5 nights. The dance was over one day. The wind blew and rough weather on account of this nobody went home. That night [after] the dance all were asleep. There were four houses and one sweat house making five in all probably including the dance house.

Some of the most industrious men left the island to gather food and water for their families, leaving behind their exhausted families after days of dancing. The lingering celebrants likely found comfort in this extended time together, sharing some final stories and meals as the February winds whipped across the bay. Children may have played among the village houses, while elders shared news from their various communities. In their homes and around the fire, the Wiyot people could reflect on the profound connection they had reinforced with the Creator and with one another. As the revelers fell asleep that night, they were perhaps hopeful of the year to come: were their prayers heard, and might they be fulfilled? The peaceful rhythms of their ancestral ceremony, echoing across the waters of Humboldt Bay, seemed to promise renewal and prosperity even in these challenging times. None could have known that this particular ceremony would be their last on Tuluwat Island for more than 150 years, or that the violence they had prayed to prevent would descend upon them with such swift and terrible force.

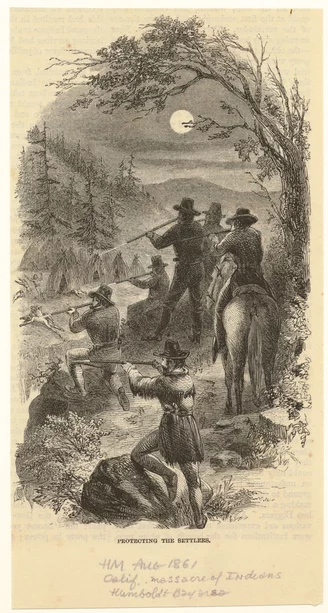

“Protecting the Settlers.” Illustration in Harper’s Magazine, Aug. 1861. Source.

Late on the night of February 25, 1860, a group of men assembled at the docks of Buhne’s Point (King Salmon).5 Armed with axes, knives, and clubs, the mob plotted attacks on Wiyot villages across the county. Five or six men rowed to Tuluwat Island around 3:00 AM in the early morning of February 26, intending to ambush the Native Americans while they slept.6 A restless woman sitting on the shore spotted the marauders before they landed, shouting to alert others.7 Some inhabitants awoke, fleeing to the nearby brush, diving into the water, and hiding wherever they could. Many Wiyot were cornered in their homes — the marauders entered the dwellings and systematically murdered people where they lay.8 Jane Sam recalled the atrocity in detail:

The doors was blocked by white men as the people were asleep, not expecting any thing to happen. They were not on the look out. When they found out what was up they began to scatter and was struck down by clubs, knives, and axes, all met the same fate, children women and men. I got out and hid in a [trash] pile. That is how I was saved. When I got away from [the trash] pile I sneaked away near the edge of the marsh by a blind slough [and] laid there.

I did not hear any noise nor scream from the people. Must of all been killed, sure enough. These white men took all things such as beads baskets fur, hide, bows and arrows. all the property belonging [to] the dead that was not taken was [destroyed] by burning. Woman and children were killed when they lay asleep or they did not make any effort to escape as they thought the white men would not molest them. A few men got away, the exact number being forgotten. At break of day I saw two boat loads of white men going across to Eureka. These were the men that done the [massacring].

About fifty-six people were killed at Tuluwat Island, three-quarters of whom were women and children.9 The murderers acted in coordination with several other marauding bands that night, continuing to target the Wiyot people for several days. At the same time the island was attacked, a raid on the South Spit killed sixty-eight Wiyot Natives.10 Villages near Buhne’s Point, at the mouth of the Eel River, and along the Elk River were also attacked.11 Smoldering homes could be seen scattered across the bay. Three days after the massacre, twenty-six were killed in an ambush at the Wiyot village near Eagle Prairie (Rio Dell). The following day, there was an attack at the “Slide” (Fortuna) resulting in an undocumented number of deaths.12 A conservative estimate would put the total number of losses at about two-hundred people.

When dawn broke on February 26, 1860, the tragic scene was brought to light. No one but the perpetrators and survivors of the slaughter could imagine the gruesome horrors that covered Tuluwat Island and surrounding villages. As one of the few survivors of the attack, Jane Sam, described the aftermath:

It took all the fore noon to gather up all what bodies men, women, children and babies could be found. One living child was found in the arms of his dead mother and today he is living. Two houses where its occupants were asleep none escaped alive. It took all day to bury the dead. The next morning they was through burying what bodies were buried on the Island. The rest of the bodies that were not buried there were taken to Mad River for burial. Some were taken to the [Peninsula,] some taken to South bay, some to [Freshwater]. This same night there was a massacre at the mouth of Eel river and at the south jetty (now) where men, woman, and children, were killed. What got away were taken to bucksport by the soldiers. I do not know how long they were kept at bucksport. From there we were taken to the Indian Reservation.

The survivors of the Wiyot Massacre carried with them a profound significance in the future of their culture. They were the progenitors of a people, the sole hope from which the Wiyot way of life could be carried on to posterity. Some survivors — such as Jerry James, the baby found in the arms of his dead mother — would go on to become influential tribal leaders, guiding the Wiyot in the eventual reclamation of their ancestral lands. Other survivors possessed essential knowledge of Wiyot craftsmanship; their expertise served as the genesis of all future Wiyot material culture. Likewise, many survivors went on to become the founders of immense lineages, families who today make up the descendants and members of contemporary tribes and rancherias throughout Humboldt County.

But in the aftermath of the Wiyot Massacre, an arduous journey laid ahead: after Wiyot survivors were congregated at Fort Humboldt and Union (Arcata), they were forcibly expelled to the Klamath Reservation in May 1860. The removal marked a decade-long struggle within the California reservation system. Those who survived this nightmare were then forced to contend with a new series of obstacles in the form of convoluted legal structures, economic barriers, and assimilatory forces like the federal boarding school system. The experiences of those who overcame this cycle of abuse reveal a story of grief and perseverance beyond comprehension.

###

Ryan Bass is a historian of Yurok-Karuk descent at Cal Poly Humboldt. After receiving the Charles R. Barnum Award for his research on the 1964 Flood and its effects on indigenous communities in Humboldt-Del Norte, he has shifted his research focus to two particular topics: the Hoopa Valley Boarding School (1896-1932) and the California Genocide (1849-1873). Published works regarding these topics is expected to be released later this year.

You like history? Consider a subscription to the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

###

1 Raphael, Two Peoples, One Place, 18-19, 168-169.

2 Kroeber, “Wishosk Myths,” 95; Raphael, Two Peoples, One Place, 18.

3 Loud, Ethnogeography and Archaeology of the Wiyot Territory, 331-332.

4 Jerry Rohde ed., Wiyot History Papers, Statement from Jane Sam.

5 Heizer, The Destruction of California Indians, 156, 256.

6 Jerry Rohde ed., Wiyot History Papers, Statement from Jane Sam; Genzoli, Robert Gunther’s Story, in Genzoli Collection, Cal Poly Humboldt Special Collections, 3; Heizer, Destruction, 255; Loud, 330-331.

7 Genzoli, Robert Gunther’s Story, 3.

8 Jerry Rohde ed., Wiyot History Papers, Statement from Jane Sam.

9 Heizer, Destruction, 156.

10 San Francisco Bulletin, March 13, 1860.

11 Charles Rossiter, San Francisco Bulletin, March 2, 1860.

12 Humboldt Times, March 3, 1860.

CLICK TO MANAGE