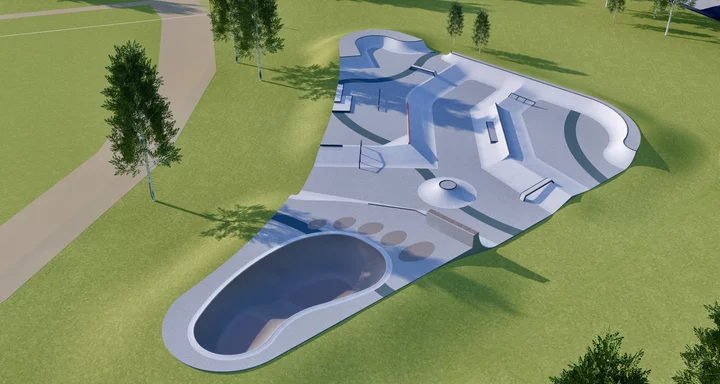

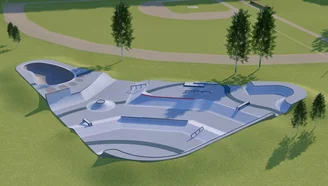

Concept art of the Bigfoot Bowl. Photo courtesy of Rich Conklin.

Good skaters make it look easy.

Saying that about supremely talented athletes is a cliche, but people say it because it’s true. The best move like liquid, devoid of any obvious effort. They jump over obstacles or through them or — why not? — hit them intentionally. The board is a partner, co-equal in a ballet that can be slow or fast or FAST and could be here, there, anywhere there is ground to ride on or air to soar through. A good skater is a dancer with total freedom. Even a complete novice or onlooker can see how they value that, so it’s striking when any of them decide to sacrifice even a small part of it.

This summer, a Bigfoot-themed skatepark opens in Willow Creek. To one of those novices or onlookers it will appear out of nowhere, but that’s only happening after some of those good skaters have voluntarily spent years and countless hours of toil embedding themselves in government, working from the ground up to make it happen.

Riley Morrison, a Willow Creek-based cannabis grower and lifelong skater, has spent huge chunks of the last 10 years attempting to build it. He moved there in 2010 from Marin, though he’s originally from Atlanta.

Morrison is a serious skater. He’s got a halfpipe on his farm and co-owns Rampart, an indoor skatepark in Arcata. On road trips, he likes to stop in towns that have skateparks and get some exercise in with his kids, who also skate, snowboard and surf with him.

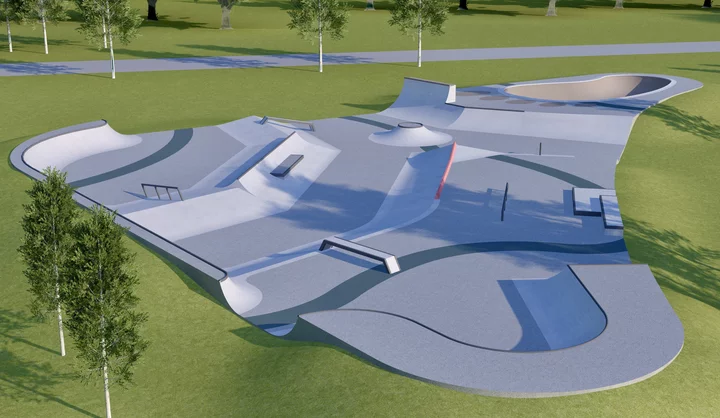

The planned upgrades to Veteran’s Park.

“I’ve always tried to stay relevant as a rad dad and provide a good outlet for these kids to enjoy themselves,” Morrison said.

Skateboarding is a simple sport to start doing. All it takes is “your brother’s old, beat-up board and his shoes,” as Morrison put it. He saw a need for a skatepark in Willow Creek when he saw how Willow Creek’s soccer team for kids nine years old and younger would get demolished when they played; all the more urban teams were actually made up of nine-year-olds, and their team would have athletes as young as five playing because they barely had enough players to flesh out a team. It wasn’t fair to pit a rural town against fully-manned teams with modern training facilities.

“[Some of those five-year-olds], we just make them get in the car and go to the game,” Morrison said. “So the kids grow up with this attitude that sports and recreation isn’t for them.”

According to Morrison, Willow Creek and the surrounding area also has a dire need for more recreational activities that young people enjoy.

“It’s a safe space where kids can go,” Morrison said, nodding while he sipped a coffee, warm in a Dead and Company hoodie the exact shade of green as his eyes. “Skateboarding saves lives! It’s the truth, you know. And to create a space like that in Willow Creek, that has accessibility for the upriver community — for the tribe, that’s a huge need. We just don’t have a space where kids can be kids. Otherwise, they get into trouble. And there’s plenty of that.”

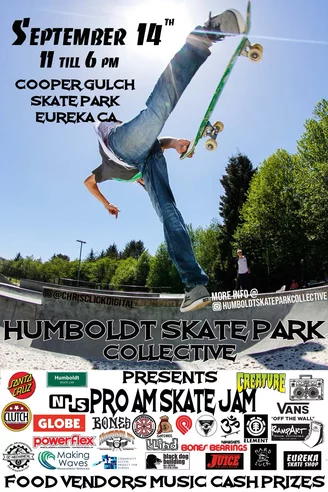

In 2015, Morrison decided it was time to do something about it, but building a skatepark alone is impossible. None of the local nonprofits wanted to attach their names to the project, due to the funding it would take and the difficulty involved. Fortunately for him, Charlie Caldwell, director of the Humboldt Skatepark Collective, was willing to help.

Caldwell, 63, is a retired PG&E project manager. He started skating when he was 7 years old.

“It’s freedom,” Caldwell said. “Even at 60, almost 64, when I get on a board, I start going into 12-year-old mode.”

Caldwell was instrumental in getting the first phase of the 5,000 square foot McKinleyville skatepark finished, though he won’t be completely satisfied until the last 15,000 square feet are done once they fundraise another $250,000.

Building a skatepark is a monumental task. It took 20 years to build even the first part of the McKinleyville skatepark; the Great Pyramid of Giza took 26. Securing the funding, getting the permits, finding a contractor and keeping the community engaged all throw up enough hurdles for a dozen horse races.

Caldwell said the most important thing he did was share a roadmap for Morrison to follow. By the time he started working on the McKinleyville skatepark, no one remembered how the parks in Arcata or Eureka were built.

“What I mostly do is encourage and give,” Caldwell said. “Because I’m a project manager, I keep everything organized and laid out, so when someone says ‘Hey, I need to do this,’ I go, ‘Here’s everything!’ It’s hugely complicated, and I’ve already walked through it.”

Morrison spent hours working with the Willow Creek Community Services District attempting to come up with something. He and Caldwell went to every meeting the CSD held for years. Eventually, they decided to work the park into a larger improvement planned for Veteran’s Park, though the Willow Creek CSD still wasn’t committed to signing a memorandum of understanding.

In 2019, four years after Morrison first started trying to build a skatepark, he and Caldwell decided to go after $4.2 million of California’s Proposition 68 funding. They had money from two skating events they hosted, and spent $20,000 on a grant writer, saving a few grand by doing all of the community outreach themselves. Over 700 people responded to their survey; only 1,500 live in Willow Creek. The proposal would include dozens of upgrades to Veteran’s Park besides just a skatepark — street lights, a better baseball diamond and a concession stand, to name a few.

They didn’t get the grant, and by this point Morrison was over dealing with the CSD, who were proving hard to work with. He ran for election in 2020 and beat the incumbent after seven mail-in votes were counted, a month and a half after Morrison had already conceded.

“This is an institutional board that is very comfortable with living in their retirement community of Willow Creek,” Morrison said, “And trust me, they want the best for the kids, but there was nothing going on with the CSD. They aren’t developing recreation. They’re not developing their assets.”

The cannabis association didn’t help Morrison either. He said he often felt stigmatized for being a grower, and said it could be hard overcoming entrenched community bias.

“There were times in the last 15 years where you kept your head low,” Morrison said. “You would go to the gas station, and then you go back. We were not accepted as a community out there. [But] since the industry has collapsed, I think everybody can appreciate what the struggle was and release their critical biases.”

Morrison and the Humboldt Skatepark Collective tried to secure another $4.2 million in Prop 68 funds in 2020, but again they failed.

They decided to try again in 2021, this time for only $1.9 million. They cut the add-ons down to nine things instead of 14. But the biggest change was to the skatepark, which they decided to make Bigfoot-themed. Morrison credits former Arcata mayor and grant writer Susan Ornelas with the idea, although Ornelas told the Outpost that it was all Morrison.

“We needed a catch,” Ornelas said. “We needed something. And I was like, ‘Everyone loves Bigfoot! I don’t know anybody who doesn’t love Bigfoot, whether you believe in Bigfoot or not…I really let my inner Bigfoot out. I suppose I kind of went for it, did a painting of [Bigfoot on a skateboard], and included that in the grant proposal.”

That time, it worked.

Everyone involved in the process said that getting the funding is, by far, the hardest part of the process. The process wasn’t done yet, though — next came bidding for a contractor and a designer, which ended up going to Primary Concrete, the same company that built the McKinleyville skatepark.

Founder Rich Conklin said his design was inspired by the nearby Trinity River, with lots of blue-colored concrete and river textures. The final design should be around 8-10,000 square feet and, of course, is very Bigfoot-centric. Skaters will be able to glide over his toes. There will be a Bigfoot interpretive center and a Bigfoot water feature and a Bigfoot sculpture elsewhere in the park.

Conklin enjoys working on this project.

“The parks that are really special are the ones that have this grassroots undercurrent and that real sense of a community project,” Conklin said. “You’re like, ‘Man, these guys have been working so hard for years and years, and fundraising and red tape and meetings — all that stuff, and I just get to show up.”

Morrison is very excited for this project to be over. His goal was to see his kids skate in the park before they graduated high school. When he started trying to get it done, they were in elementary school. Now, they’re 14 and 16 years old.

Ten years to build a skatepark, from inception to delivery, is not a long time. Morrison attributes the success to timing and persistence, likening the process to building an airplane while you’re flying it.

Willow Creek’s electorate voted him in for another term on the CSD, but he’s eager to finish out his career in politics in a few years, stop growing weed someday and focus on his kids and skating.

“I don’t want to be in politics anymore,” Morrison said. “It’s like a Chinese finger trap…I look forward to the day I can stop growing weed and grow more vegetables. That’s how you’ll know I’m retired…The weed can come and go, but we got a skatepark. That concrete isn’t going anywhere.”

CLICK TO MANAGE