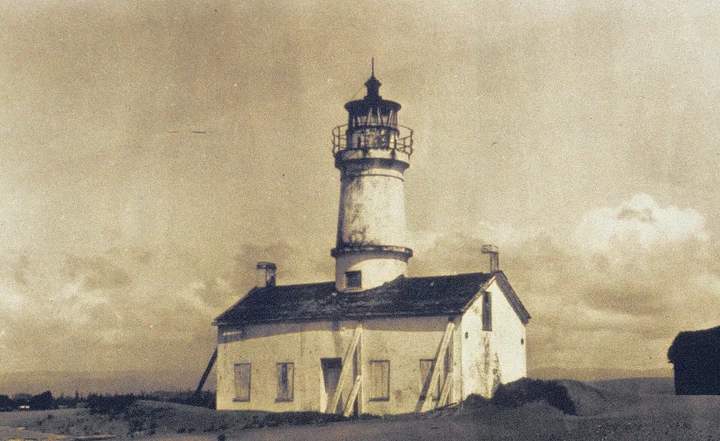

The original Humboldt Bay lighthouse on the North spit in 1920, long after it had been deactivated. Author: Unknown. Public domain.Via Wikimedia.

Humboldt Bay is a natural land-locked bay about 100 miles south of the Oregon state boundary. It lies in an indentation, or bight, in the coastline and is one of the few natural bays on the Pacific Northwest coast. It is approximately fourteen miles long and varies in width from three and a half miles to a half mile, with an average width of three quarters of a mile. Several small creeks empty into the bay, but no streams of consequence are tributary to this waterway.

The bay is separated from the ocean by two narrow sandy spits, whose ends form the entrance. A mile seaward of the spit heads lies a sand bar, a typical formation on the Pacific Coast.

Major William W. Harts, of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, described the sand bars found at all of the harbors along the coast. The harbor entrance is “obstructed by a crescent-shaped encircling bar. …The distance and the depth of water overlying the bars are largely dependent upon the area of the tidal prism within the bays and the exposure to storm action.” Through the bar, and the entrance, are channels carved in the sand by the tidal action. At Humboldt Bay “the channel through…[the] entrance, in its natural state, was shifting and dangerous, being uncertain as to position, width and depth, and averaging a mile in length.”

Complicating the uncertainty of the channel is the stormy conditions that are prevalent on the coast. It has been maintained by ship masters “that nowhere else have they encountered such waves as off Humboldt.” The entire crescent of the bar in its unimproved state was frequently a field of breakers. The dangers and hazards of the entrance to Humboldt Bay stem from the combined conditions of the bar, the violent and unpredictable waves, and the shifting and often shallow nature of the channel.

As early as 1850, when Hans H. Buhne first piloted the schooner Laura Virginia into Humboldt Bay, the dangers of the bay’s entrance were recognized. The passengers and crew of the Laura Virginia formed an association that was searching for the bay whose discovery by the Josiah Gregg party had been reported in San Francisco.

After seeing a smooth stretch of water that was presumed to be the bay, Buhne, the second officer, was sent to take soundings and see if it was possible to guide the Laura Virginia into the bay. After having crossed the bar in a small boat that was swamped twice before reaching land, Buhne returned and guided two more of the Laura Virginia boats into the bay. The passengers in one of these boats became so apprehensive that they almost refused to cross the bar after seeing the “terrific breakers… [that] mark…[the] line where the waves of the ocean meet the ebb tide.” The entrance to the bay itself was almost obscured by those breakers.

Despite the hazards encountered by Buhne and the Laura Virginia Association, the full extent of this navigation barrier to trade and development was not immediately recognized. The early settlers did not have many exports, and the shipping was limited. For example, during the first half of 1852, only six vessels from the Humboldt region arrived in San Francisco. The rise and development of the lumber industry rapidly changed the numbers of ships upon the bay. Only a year later 143 ships made the trip to San Francisco from Eureka with large loads of lumber. The full threat of the bay entrance to shipping became obvious by the late 1850s. By 1855, even with a tug in operation to guide schooners in and out of the bay, twelve ships had been wrecked trying to navigate the entrance. The alternate to risking a crossing when the entrance was rough was to remain “bar-bound” for days, unable to cross the bar because of the high waves.

During the stormy winter months ships were often kept in the harbor for weeks, unable to leave with their valuable cargoes of redwood lumber. Other ships found it necessary to leave the bay only partially loaded so that they could make it across the bar with its shallow channels.

The maps of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey were an attempt to help mariners enter the harbor. The earliest map done by the Survey in 1851 gives the following advice on how to enter and find the bay. The sailing directions began with a description of the bay:

This harbor may be easily recognized by a remarkable red bluff facing the entrance with a perpendicular front to the sea of 96 feet, and by the headland known as Table Bluff, five miles to the southward. To enter the harbor, bring Howard’s House (a large four story white house), to bear by compass S.E. and well on width a point of trees on the highland two miles back. Run in on this range until across the bar, when the breakers on either side of the channel will be sufficient guide to the anchorage.

These directions were only satisfactory for a few years. The natural erosion of the heads of the spits by the waves greatly altered the entrance by 1858. The channel had also moved from a northwesterly position to an almost due west location. Recognizing the variableness of the channel, the coast survey maps, beginning in 1858, no longer gave sailing directions and the individuals crossing the bar were dependent upon the pilots for help.

An example of a typical crossing experience is described by some of the soldiers and their wives who came to establish Fort Humboldt in January of 1853. The notorious reputations of the entrance was known by all on board the steamer Goliah. When the Goliah reached the bay, the Captain, “Old Bully Wright,” found the bar too rough to attempt a crossing. It was necessary to wait until the following day when the conditions were more favorable for a crossing.

Wright refused to signal for a pilot, believing that he knew the entrance as well as anyone. The surgeon’s wife, Mrs. Underwood, was not as sure about their safety when she saw the “masts of several wrecked vessels that were evidence of the dangers of ‘crossing the bar’.” Lt. George Crook was also concerned about making the difficult passage. He commented in his autobiography that “we labored on the bar, the old ship nearly breaking in two. All on board experienced great relief when we were safely over.” Most who crossed the bar felt a similar relief in finding that they had survived the treacherous crossing. Not all were as lucky.

With the increase in shipping, stimulated by the rapid growth of the lumber industry and the development of agricultural pursuits, came an increase of tragedies involving the crossing of the bar. An example is a drowning accident that occurred in February 1870. The Humboldt Times reported that the Captain of the brig Crimea had been washed overboard. Captain Lassen was the sole owner of the brig, and was concerned with its safety while crossing the bar. The brig was towed out of the entrance and across the bar through the channel by one of the tugboats on the bay. Lassen was last seen “in the main rigging of his vessel, but no one saw him when he fell or was carried overboard by the sea, nor indeed, does it seem that he was missed until she had cast off from the tug.” It was the consensus of the crew that Captain Lassen had been washed overboard by one of the several heavy seas that had hit the Crimea while she was crossing the bar.

The dangers of the bay entrance were cited in the statistics of the United States Life-Saving Service whose annual reports “chronicle more terrible shipwrecks at Humboldt Bay than at the great port to the south (San Francisco).” Though the dangers of the bay entrance were recognized, little was done to lessen the hazard in the first forty years following the settlement of the Humboldt Bay region.

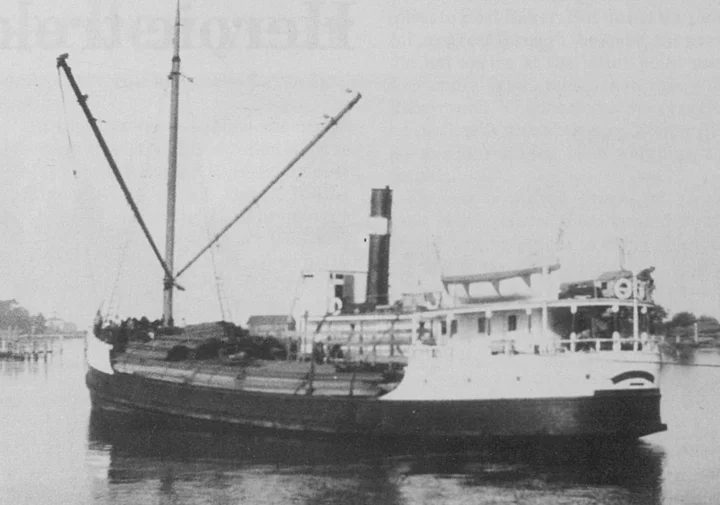

One of the most tragic bar wrecks, in terms of loss of life, was that of the lumber steamer Brooklyn, shown above, in its prime. The photo below shows all that remained after the vessel rolled over crossing the bar in high seas on Nov. 8, 1930. Of the crew, 19 men were lost and one survived. Photos via the Humboldt Historian.

The first step taken toward greater Humboldt Bar safety was the erection in 1856 of a lighthouse tower near the entrance, on the North peninsula, by the lighthouse service. The money for building the tower was first appropriated in 1851, but construction was delayed by inadequate funding, poor transportation, and problems with contractors. These problems, caused by lack of foresight, continued to plague all future improvements on Humboldt Bay in the nineteenth century. Even after the tower was completed, inadequate planning resulted in more construction. For example, when mariners complained that the original structure was too low, it was necessary to raise the tower several times. It was almost twenty years after the lighthouse was completed that a bell boat was added in 1872 to the entrance warning system to help warn ships during the dense fogs that plagued the coastline. In one year the keepers at the Humboldt lighthouse logged “over 1,100 hours of fog.” Due to the stormy weather the bell boat was short lived, and was replaced in 1874 with a steam whistle.

Despite the continual improvements to the lighthouse and its warning system, mariners were still dissatisfied with the performance of the lighthouse. In 1886, after a series of severe storms and unusually high tides had nearly destroyed the structure. Congress was petitioned for permission to move the lighthouse to the nearby large bluff four miles to the south of the bay entrance. Other reasons for removal of the lighthouse were the complaints of mariners and the opinion of the Lighthouse Board that the bay entrance was not the best location for the structure. It was the belief of the Lighthouse Board that the proximity to the Humboldt bar, with its constantly breaking waves, not only cut “the sound of the fog signal, but it also obscures the light when the weather is generally clear.” The Humboldt lighthouse closed on October 31, 1892, and the Table Bluff lighthouse began to warn of the dangers along the Humboldt coastline. The buildings of the old lighthouse would be used by the engineers of the Army Corps while they sought other, more concrete ways to improve the entrance to Humboldt Bay.

One of the first to call for more physical improvements was the editor, William Ayres, of the Democratic Standard. Ayres, beginning in 1877, began agitating in his editorials for “securing congressional assistance for the improvement of our harbor.” He was convinced that the natural potential of Humboldt Bay as a shipping harbor needed to be developed, and the only way to do that was by creating an entrance and harbor that allowed easy ingress and egress of ships of great draft.

Ayres was a man of vision. He saw Eureka and Humboldt Bay as becoming the commercial center of Northern California. He believed that with an expenditure as low as $300,000 the bay could be improved and that Eureka and Humboldt Bay could become “inevitably…the great initial shipping point for all foreign vessels engaged in the redwood lumber trade and for the great bulk of the shipping that is done from Humboldt County, particularly for all that portion any considerable distance inland.” With this object in mind, Ayres worked diligently for his cause during the seven years that he was editor of the Democratic Standard. It was largely due to his activities that the attention of Congress and the Army Corps of Engineers was drawn to the Northern California bay, and a series of attempts launched to improve the bay entrance.

Ayres’ first editorials met with little success. He was not dissuaded, and argued frequently and articulately about the benefits to be gained from improving the bay. It was Ayres’ belief that the harbor improvements would help not only Humboldt County, but also the surrounding counties of Del Norte, Siskiyou. Trinity and Shasta. He hoped that with the support of these counties it would be possible to get the attention of Congress and its support for the improvement of the bay.

Ayres’ estimate of $300,000 to improve the entrance was too great a sum for the recently formed County of Humboldt or City of Eureka to finance. It was also too great of a sum to be raised from the lumber barons who stood to profit most from the scheme. The industry was recovering from the severe national depression of the 1870s and was little inclined to fund a project of unknown results. Thus, it was necessary to turn to the federal government, who through the Corps of Engineers during the Nineteenth Century had become increasingly active in harbor and river improvements, in the interest of both national security and commerce.

It was the Corps whom Ayres wished to reach, as they had the knowledge, technical expertise and experience to improve the bay entrance.

It was Ayres’ belief that by increasing the depth of water across the bay by six feet a great surge in the amount of shipping would result. It was necessary for him to convince such doubters as Captain Hans H. Buhne, who had piloted the Laura Virginia, and, as late as 1881, still maintained that it was impossible to improve the treacherous entrance. In order to convince Buhne and others, Ayres turned to economic justifications for his plans.

In an article on April 27,1878, Ayres explained how the additional six feet of water over the bar would benefit the shippers on the bay by using a concrete example of the cost of shipping a million feet of lumber from Eureka to San Francisco. Under the conditions of the period, it was necessary to ship that amount of lumber in at least five different cargoes. The cost for shipping the million feet at the 1878 shipping and towing charges on the bay came to $5,750. According to Ayres, with an increased depth on the bar ships of greater draught could utilize the harbor and it would only be necessary for two cargoes to transport the million feet of lumber. Ayres then argued that lower rates could be charged for both the towing and shipping charges. Using the contemporary costs of towing and shipping, Ayres believed the increased depth of the bar would result in a savings of $45,000 for the individual shipper. These statistics would have been very impressive to the lumbermen in the area who were recovering from a devastating national depression.

Beyond the immediate savings to the lumber companies, Ayres was convinced that the improved entrance to Humboldt Bay could result in an increase in the amount of shipping. The lower charges would open up foreign markets to redwood lumber which had previously been closed because of high shipping costs. Ultimately, Ayres argued, the additional six feet of water over the bar would result in the immediate doubling of the “value of every foot of redwood timberland in our county or contiguous to it. Thinking minds who are interested in the growth and development of this section should consider this proposition well.”

###

Next: The rocky course toward bay improvements.

###

The story above is excerpted from the January-February 1989 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE