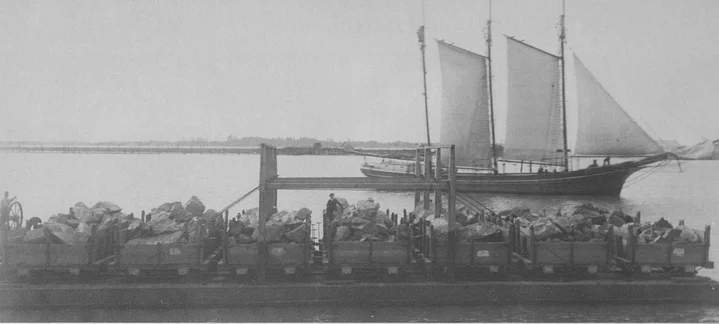

A barge on Humboldt Bay hauls cars loaded with rock for the jetty project. A sailing schooner is in the background. This was near the turn of the century. Photos via the Humboldt Historian.

PREVIOUSLY:

###

One of the first to call for extensive improvements to facilitate shipping across Humboldt Bay Bar was William Ayres, editor of the Democratic Standard. He began his campaign through editorials in 1877.

He proposed that a jetty system, such as the one built at the mouth of the Mississippi River, could result in a safer and deeper entrance channel. His recommendations were rather revolutionary for the reason that jetties were only recently tried and many were skeptical about the results.

There, at the South Pass channel of the Mississippi River mouth, civil engineer James B. Eads, funded by the federal government, had been able to. with jetty construction, increase the depth of the channel at the river mouth from eight feet to 24 feet. With the completion of the jetties at the South Pass in 1877, the “oceangoing ships of the largest size were regularly entering the Mississippi by the smallest of the major passes.”

It is no wonder that Ayres was impressed with the possibilities and potential of jetties to improve the entrance to Humboldt Bay. The conditions at the mouth of the Mississippi were similar to those at the entrance to Humboldt. Trade along the Mississippi was hampered by the large sandbar of the delta, and only ships of shallow draught could make it over the bar. The wave and storm action was less violent then at Humboldt, but Ayres was confident that the problems presented by the stormy North Coast could be overcome, especially by an engineer of Eads’ abilities.

In January of 1879 Ayres had sent Eads a description of Humboldt Bay, and the conditions of the Bar, with a plea for his opinion on the feasibility of improving the entrance. Eads’ response was very positive. After examining the maps sent to him by Ayres and looking at the United States Coast and Geodetic survey maps, Eads was of the opinion that jetties could satisfactorily improve the entrance. In fact, Eads was confident that “the channel through the bar obstructing the entrance into the bay can be permanently deepened by the aid of jetties.” Eads was also willing to travel to California, and examine Humboldt Bay if Ayres or the community would pay Eads $3,000. Eads commented that he was asking for such a modest sum because he was interested in the project and was aware that it would be necessary for a few public-minded citizens to raise the money.

Eads also wrote that he was influenced in making the proposition “more from the desire to aid … in inaugurating and consummating an interesting and important public work.” It must be noted that Eads was a very polished and skillful politician, but it is possible that he was genuinely interested in the improvement of Humboldt Bay.

With the publishing of Eads’ letter, Ayres became very active in trying to raise the money required by Eads. Ayres was particularly hopeful that Eads could examine Humboldt Bay for several reasons. Recognizing Eads’ political clout, Ayres was convinced that a “favorable report from Captain Eads on this proposed work, a memorial to Congress, would be almost sure of gaining the required appropriation.” It was with this goal in mind that Ayres called for a public meeting to “discuss the subject of improving Humboldt Harbor.” The meeting was held on March 19, 1879, and was supported by many of the influential members of the community. Such lumbermen as John Vance, William Carson, and John Dolbeer offered their support to the meeting as did politicians and businessmen C.S. Ricks, E.H. Howard, and Joseph Russ. Despite the support and interest in Eads’ proposal, Ayres was unable to raise the necessary funds.

The interest sparked by the Eads’ correspondence did result in an increase in the awareness of the problems to trade caused by the bar and its shifting channel. Eads, without traveling to Eureka, was able to draw the attention of some congressmen to the condition of the harbor. A few weeks after the meeting to raise money for Eads to travel to Humboldt County, Ayres received a letter from Congressman J.K. Luttrell. Luttrell had been in correspondence with Eads and was very supportive of the proposal to have Eads visit Humboldt Bay.

Luttrell was an influential Democrat to have on the side of the supporters of the improvement of Humboldt Bay. He had recently introduced bills in Congress calling for “appropriations for the improvement of our harbors along the coast between San Francisco and Puget Sound.” Beyond these general bills, Luttrell had also helped to pass an appropriation bill of $250,000 to be used to develop a harbor of refuge on the Pacific Coast north of San Francisco. The specific site was to be chosen by the Army Corps of Engineers. The need for improvements on Humboldt Bay had finally been brought to the attention of Congress.

With the congressional interest came the assignment of the San Francisco District of the Army Corps of Engineers to the problem of improving Humboldt Bay. The San Francisco district was not unfamiliar with the bay, the bay having been examined both in 1871 and 1877 by a Board of Engineers. The Board was seeking to find a bay or harbor along the Pacific Coast that would be suitable to develop as a harbor of refuge. The coast line between San Francisco and the mouth ofthe Columbia River was devoid of a safe harbor for ships in danger and none of the few natural bays or river mouths were of sufficient depth to allow the large naval ships to enter. Humboldt Bay was a logical choice for the Board of Engineers to examine, because of its location almost halfway between San Francisco Bay and the mouth of the Columbia. Humboldt Bay was considered as a possibility for being improved to be used as the harbor of refuge, but was passed over for several reasons.

In 1871, with the encouragement of district Congressman James A. Johnson, the Corps of Engineers made its first examination of Humboldt Bay. The members of the examining board returned a negative response on the feasibility of improving the bay. This finding was made despite the Board’s opinion that once vessels had entered the bay “it is the best harbor on the Pacific Coast between San Francisco Bay and the mouth of the Columbia River.” The problem with the bay was the uncertainty of the entrance. R.S. Williamson, a Major in the Corps of Engineers, in a report to Chief of Engineers Brigadier General Humphreys, described the bar and the obstacles it presented:

The bar, like nearly all ocean bars on the Pacific Coast of the United States is constantly changing. Every severe storm changes the channel; sometimes there are two channels, and sometimes there is but one. In rare cases the channel is so closed that the steamers cannot go out.

Williamson goes on to relate that he himself had been “bar-bound” in December of 1865 for a fortnight. A storm had arisen shortly after his arrival, and destroyed the old channel. It took two weeks for a new channel to open sufficiently to let out the passenger steamer. Williamson adds that no vessel “enters or leaves the bay without a pilot.” Ultimately, it was Williamson’s opinion that such a bar as the one at Humboldt Bay “can never be improved.”

Of the members of the Board of Engineers, Williamson was the only one who had actually been to Humboldt Bay. The Board’s report “on the practicability of improving entrance to Humboldt Bay and Humboldt Harbor, California,” was made without a personal examination. Instead, the report was based primarily on the coast survey chart, “the well-known shifting sands forming the bar and the concurrent testimony of all persons acquainted with…[the bar].

The Board, in spite of the lack of first-hand knowledge, presented two possibilities for the improvement of the bay. Both plans included jetties and both ended in a supposition of disaster. Moreover, neither plan proposed by the Board was considered very practical. The Board believed that the cost of construction would far exceed any possible benefits, which they deemed would be short-lived.

The 1871 report illustrated the skepticism with which jetties were viewed at the time, and the lack of knowledge of what the jetties could or could not accomplish. The two jetty systems proposed by the Board revealed the prevalent attitudes on jetties held by the army engineers. The first example presented by the Board was two jetties or pierres perdues, to use the French term, of stone or masonry. These jetties would confine the channel and secure the depths necessary to allow heavily loaded ships to easily enter and leave the bay. The Board believed that these jetties would easily be destroyed, and leave “the stones or the disjointed masonry…scattered over the bar as so many dangerous obstructions.” Similarly, the Board thought that jetties built of “sufficiently powerful construction to withstand the force of the sea, properly located, and carried out to, say 10 fathoms of water, with their foundations laid so deep so as not to be undermined, we have no doubt but their effect would be to improve the entrance to the harbor, till such time as the resulting currents should accumulate another bar outside of the supposed entrance between such structures.”

This official opinion about the infeasibility of improving the entrance to Humboldt Bay was to mark the Corps’ attitude for the next ten years.

In 1877 the Corps was again directed by Congress to attempt to locate and improve a harbor of refuge as none had been found suitable in the 1871 report.

Specifically, Congress directed the Corps to examine, in addition to the harbor of Humboldt Bay, the harbors of Mendocino, Trinidad and Crescent City. The Corps was to examine each bay, with the aim of finding one that could be made suitable as a harbor of refuge with the construction of a breakwater, and an estimate of cost. It was the final criteria that caused a negative response for Humboldt Bay. The Board believed that two parallel jetties, built out 500 yards apart from the sandy entrance heads could result in a safer entrance to the bay but was convinced that “such construction would be attended with immense difficulties and enormous expense.” One of the reasons for the great expense was the lack of close quarries for the rock to construct the jetties. The Board was also unsure if jetties could be constructed on the sandy heads without collapsing. The Board itself was divided on whether or not the “the construction would be physically possible.” The three-member panel had been unable to closely examine the bay entrance due to the rough condition of the bar, and so were unsure of the results that could be obtained by jetties.

They were impressed with the dangers of the entrance, and the need to improve the bay, however. When they arrived off the bay, aboard the coast steamer Hassler, the pilot had refused to guide the steamer over the bar, even though the weather was moderate, mid-August weather. Further, at the time there was a depth of 20 feet over the bar, and the Hassler drew only 12 feet. The pilot was adamant in his position, stating that he could not bring the Hassler into Humboldt Bay “without running the risk of the vessel striking bottom and her possible loss in the breakers.”

The engineers were forced to accept the pilot’s assessment of the situation. Perhaps in light of the uncertain and often violent condition of the ocean near the entrance to Humboldt Bay, the Board deemed it “highly improbable that a breakwater or jetties would be attempted here at the present time.” The estimation of the Board was accurate, as it was not until 1889 that construction was first begun on the Humboldt jetties.

Despite the two negative reports by the Corps of Engineers, the influence of Ayres and Eads resulted in yet a third examination of Humboldt Bay by the Corps. In 1881 Lt. Colonel George H. Mendall, the San Francisco District Engineer, submitted a favorable report on Humboldt Bay development. This decision marked the first Corps work done on the bay and the first congressional appropriation for the bay improvement. The project consisted of dredging the bay, “mainly in front of the town of Eureka, where the channel has been shoaled in late years. It is proposed to give 10 feet at low water.”

Congress approved $40,000 for this first project. In addition to the dredging, which would be done by W.B. English, the Corps was also to examine the entrance closely, seeking a better understanding of the conditions of the bar. The Corps was well aware of the general situation, as they succinctly stated the general characteristics of the bay entrance in their annual report. The bay entrance “is over a bar, unstable both as to direction and depth, and exposed to an extremely heavy sea in southerly weather.” With an engineer assigned to the bay, it was hoped that he could determine the best way to obtain some degree of control over the entrance channel. It was just a few years later, in 1889, that the hoped-for bar improvements began to materialize with the start of jetty construction.

Small locomotives in this 1914 scene haul rocks during jetty construction.

###

The story above is excerpted from the March-April 1989 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE