Miss Fish’s dancing class poses for a photograph in Sequoia Park on April 27, 1918. Ruth Brown (Chapman) is at far right. Images via the Humboldt Historian.

Rain fell, wind blew, and muddy rivulets flowed down Eureka’s streets on the night of December 22, 1893. Nevertheless, drenched horses and buggies kept pulling up in front of the brightly lit Russ Hall, which by nine o’clock was filled with “clowns cutting all kinds of capers, flower girls, dancing girls, and ladies from oriental regions frolicking gaily with old tars and dudes galore.” Welcome to an early-day masquerade ball!

At eleven o’clock on this night the masks were removed and the capering “Clowns” revealed to be Messrs. Ricks and Falk; the elegant “Birds of the Forest” to be Ivy Cutten; and the mysterious “Stranger” to be P. Stiger. According to the next day’s Eureka Nerve: “The floor was now at the disposal of all who cared to trip the light fantastic, and when the music of the Ideal Orchestra again pealed forth ‘with its voluptuous swell’ there was no end to the merriment until the wee sma’ hours.”

The Victorian-era ballroom exerts a certain fascination,perhaps because events there are always prefaced with the word “grand.” In a dreamy moment, we may even imaginatively transport ourselves to one of these grand balls, where of course we have striking figures, dashing attire, and expert knowledge of all the dances. In fact, this last attribute may well have been true. Male or female, had we grown up in Humboldt in the early 1900s, we probably would have learned to dance as children at Miss Fish’s dance academy in Eureka, or at Professor Gustin’s dancing school — though as ten-year-olds we may not have viewed the opportunity in a romantic light. Dancing classes, held on Saturday afternoons, required ones best clothes and deportment.

Ruth Brown (Chapman) of Arcata was a young student of Miss Fish in 1918. Every Saturday she made the trip around the bay to Eureka with her friend Mary Brizard (Duke) in grandmother Brizard’s four-cylinder, seven-passenger Cadillac, chauffeured by long time Arcata resident Frank Anderson. Miss Fish and her assistant, Dorothy Heasman, taught the children the fox trot, waltz, two- and three-step, Virginia reel, Highland fling and more. After class, the Cadillac made what the girls considered its most important stop — at the Hinch, Salmon, and Walsh grocery store where, in Ruth’s words, “We bought the biggest, most delicious homemade cream puffs we had ever eaten.”

Dancing was central to social life in these early days, and if a fellow didn’t have the opportunity to take lessons as a youngster he might seek them out on his own as a teenager, as did Rudolph Hipp of Eureka in the early 1900s. At age fourteen, Hipp signed up for dancing lessons with Professor Gustin, who had a dancing school in Russ Hall at Third and G Streets in Eureka. Gustin is listed as a dancing teacher in the county directories as early as 1902 and as late as 1917. With his tall, graceful bearing, his swallowtail coat, and his impeccable manners. Professor Gustin recalls Charles Dickens’s iconic Victorian dancing master, the nimble Mr. Turveydrop, always seen “in the full luster of his deportment.”

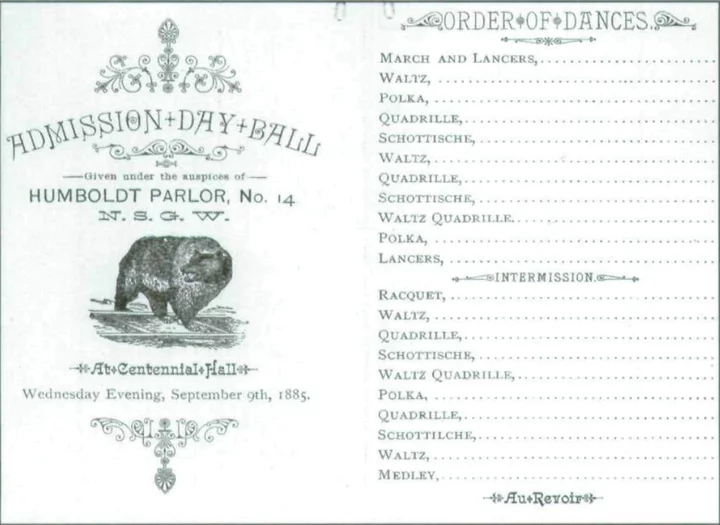

When the music started. Professor Gustin showed the boys how to cross the room graciously and ask the girls on the other side, “May I have the pleasure of this dance?”’ He taught the waltz, two- and three-step, quadrille, and lancers.

Once equipped with the necessary steps and deportment, Rudolph Hipp joined his fellow Humboldters in attending dances all over the county. Even on ragged winter-time roads, folks eagerly traveled from outlying towns to Eureka’s well-appointed halls, like Loheide’s on 5th Street, where the Winter Night Social Club balls were held. Conversely, Eurekans headed out of town to the open-air dances at Scotia, Blue Lake and Rohnerville. In the summertime, everyone jumped on a Coggeshall and Cousins lumber scow, offered for the day to dancers and picnickers, for a ride to the big dance pavilion at New Era Park in Fairhaven.

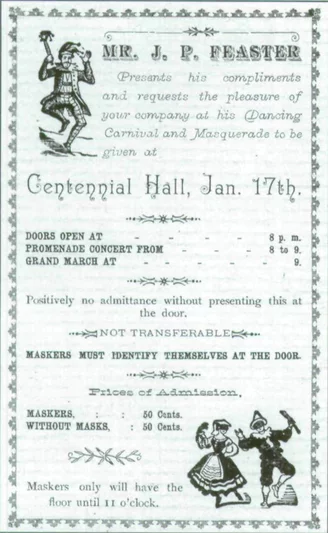

Most intoxicating to read about for the would-be time traveler are Humboldt’s masquerade balls of the 1880s, 1890s, and early 1900s, especially popular during the winter holidays. These balls began at 8 or 9 p.m. with the grand march. Maskers promenaded through the hall showing off their wondrous costumes, while a hundred or more spectators — those of less fortunate stations and means — looked on from the gallery and sidelines and endeavored to guess the true identities of the maskers. But costumes were more than just ornate garments: They indicated specific characters from “Queen Elizabeth” to “Hayseed,” which the maskers would “put on,” endeavoring to sustain their characters as long as possible through the night.

Where did these extravagant costumes come from? When a masquerade ball was announced, local merchants, such as McLaren’s music store in Eureka, would order costumes from San Francisco, and they would arrive on steamships at Eureka’s docks. At a mask ball at Buhne’s Hall in the early 1880s, Mrs. McLaren, who may have enjoyed first choice of costumes when they were unpacked in the McLarens’ shop, arrived as “Gypsy” in a “Turkey red dress with black sash and cap.”

Costumes, of course, can provide an exhilarating sense of freedom, and this must have been especially true for women in the strait-laced 19th century. The masquerade ball was a chance for a respectable woman to let down her hair, as Mrs. G. F. Roberts did at Buhne’s Hall when she dressed as “Folly” in a “short pink dress trimmed in black silk points and bells, bullion fringe and black lace, a Foily cap of black and pink silk, and hair flowing.” One feels certain that Mrs. G. A. Knight enjoyed herself that same evening as “Jockey Girl,” in a “short white skirt, blue silk basque trimmed with blue fringe, puffed bosom, high boots, horse shoes, and a whip.” And Miss Garrie Pratt gave herself ample opportunity to cavort when she assumed the role of “Dolly Varden,” the flirtatious and flashy Dickens character from Barnaby Rudge. Her lively costume featured a “short red skirt trimmed with black velvet, blue stockings, and big boots.”

What costumes and characters did the men inhabit on this occasion? Theodore Minor of Arcata was “Romeo” in a “black velvet frock trimmed with silver, white tights, and black cap with an ostrich plume.” W. J. McNamara was “Shylock” in a “purple turban trimmed with white, purple coat, red balloon pants, and a fierce mask.” Herbert Butterfield was “Spanish Lord” and Henry Buhne was “Red Devil,” while Harrison Jones and Fred Inman were “clowns,” M. S. Taylor was “Dunce” and F. H. Gibson was “Harlequin.”

Men also relished the chance to cut loose, dressing as clowns, monkeys, devils and drunkards. The many fine points of ballroom etiquette, listed below, must have been difficult to adhere to while enacting some of these comical characters.

A high point of every masquerade ball came at 11:00 p.m., when masks were removed, identities revealed, and prizes awarded. At the April 18, 1892 Grand Masquerade Ball at Armory Hall in Eureka, with music by tbe 10th Battalion Band, the prize for best dressed lady and gentleman went to Mrs. Heber as “Moorish Princess” and Charles Jackson as “King Philip,” while the most original character award went to Joseph Meyers as “a candidate for the home of the inebriate.”’ At the Thanksgiving Masque Ball in 1893, also at the Armory and attended by four hundred people, Asa Stemmons as “Old Soak” won a pair of gold cuff buttons for the best sustained character, and Mrs. M. Minard won a silver plush jewel casket for her costume, which, reports the Nerve, “would consume more space than is available to describe.”

After prizes came a midnight supper. For dances at the Armory, hot chicken and turkey suppers were served across the street at the Grand Hotel at tables serving two hundred guests at a time. After supper, dancing resumed until 4:00 a.m. Admission prices to an 1892 ball at the Armory were as follows: “Gents, $1; ladies in costume and mask, free; spectators, gents 50 cents, ladies & children, 25 cents.” Supper was fifty cents per plate.

Inevitably, rowdies were attracted to dances no matter where they occurred in Humboldt County. The Union’s report on the Christmas Eve Ball at the Trinidad Town Hall in 1900 expresses amazement that “everything passed off pleasantly, the absence of everything approaching hoodlumism being remarkable.” The announcement in the Humboldt Standard for the 1992 Easter night masquerade ball at Armory Hall proclaims: “A policeman will be in attendance to keep out disreputable characters, as this must and shall be a select and grand masquerade ball.”

For security purposes, special invitation cards were required for admittance to the ballroom. These passports to grandeur could be acquired by “all respectable ladies and gentlemen” at the shops, like McLaren’s or Dayton’s music stores, where one rented one’s costume. But invitation cards could fall into the wrong hands; interlopers, hidden behind masks, could walk in undetected. Therefore, at some masquerade balls, guests could not gain entrance to the ballroom until they first passed through a private entry room, where a floor manager discreetly checked their true identities.

Humboldt County dances continued to be central to community life right up through the 1950s. But the golden age oí masquerade balls with their grand marches, midnight suppers, and dancing until 4:00 a.m. seems to have come to an end as the twentieth century got underway. As the population grew beyond the scope of everyone knowing everyone else, and community life became more complex, a need for boundaries and regulation was voiced. In 1915, a dance hall ordinance was adopted in Eureka which prohibited the attendance at dances of unchaperoned girls under age sixteen, and forbade public dances to run after midnight without a special permit from the mayor.

But once upon a time on the Humboldt frontier, masquerade balls held sway. These extravagant affairs attracted just about everybody, from the social elites to the simple ordinary folk. Each ball, after all, brought a fresh chance to adopt a new persona. One must decide what one will become — queen or gypsy, king or clown, knight or inebriate?

###

SIDEBAR: The Etiquette of the Ball

Most early-day households had an etiquette book at the ready. These rules of ballroom etiquette are from Hill’s Manual of Social and Business Forms by Thomas E. Hill, published in 1881. The book, now on file at HCHS, is from the home of a 19th century Humboldt County family.

No gentleman should play the clown in the ballroom. Dancing a break down, making unusual noise, swaggering, swinging the arms about, etc., are simply the characteristics of the buffoon. A gentleman who goes to a ball should dance frequently; if he does not, he will not receive many invitations afterwards; he is not invited to ornament the wall and “wait for supper.”

Ladies will consult their own pleasure about recognizing a ballroom acquaintance at a future meeting.

No gentleman should enter a ladies’ dressing room at a ball. It is not necessary to bow more than once, though you may frequently meet acquaintances upon the promenade; to bow every time would be tiresome.

No gentleman should use his bare hand to press the waist of a lady in the waltz. If without gloves, carry a handkerchief in the hand.

No gentleman whose clothing or breath is tainted with the fumes of strong drink or tobacco, should ever enter the presence of ladies in the ballroom.

When the company has been divided into two different sets, do not attempt to change from one set to the other, except by permission of the master of ceremonies.

Ladies should not be allowed to sit the evening through without the privilege of dancing. Gentlemen should be sufficiently watchful to see that all ladies present are provided with partners.

###

The story above is excerpted from the Winter 2008 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE