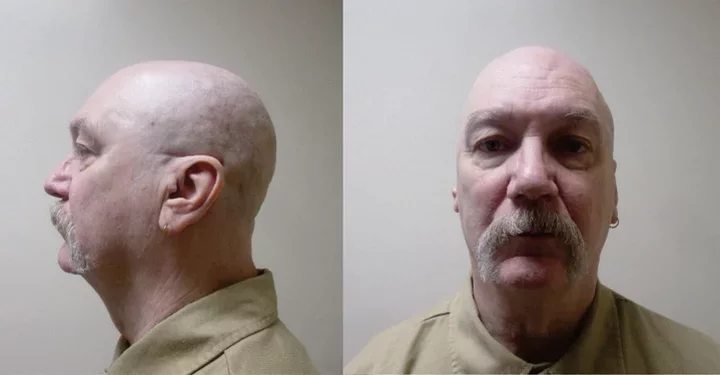

Richard Stobaugh. | Photos from California Dept. of State Hospitals via Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office.

###

PREVIOUSLY

- Sheriff William Honsal Pens Open Letter to Express Opposition to Release of Sexually Violent Predator Into Humboldt

- TODAY IN SUPES: Board Opposes Relocation of Sexually Violent Predator to Manila

- Placement Hearing for Sexually Violent Predator Delayed by Missed Filing Deadline; Prosecutor Alleges Stobaugh Possessed Child Pornography in State Hospital

###

WARNING: This story contains details of child pornography and sexual violence.

###

The question of whether sexually violent predator Richard Stobaugh should be released back into the community remains open tonight following an all-day hearing that explored the implications of his reported possession of child pornography while confined to a state mental hospital.

Appearing before Humboldt County Superior Court Judge Kaleb Cockrum, Senior Deputy District Attorney Whitney Timm called a series of witnesses who testified that Stobaugh was found in possession of a contraband hard drive in 2018 and that the device contained folders with pornographic photos and videos of underaged girls. Timm argued that by failing to disclose this information to his treatment team at Coalinga State Hospital, Stobaugh revealed himself to be “deceptive by nature,” a man who remains a predator who’s unsafe to be released.

Meanwhile, Humboldt County Public Defender Luke Brownfield, who is charged with defending Stobaugh, questioned whether the hard drive belonged to Stobaugh or to another inmate altogether. And a pair of mental health professionals testified that, even with the evidence of child porn possession, they stand by their professional assessments that Stobaugh is appropriate for conditional, supervised release.

Stobaugh was sentenced to prison in 1988 for a series of violent sexual assaults, and in 2012, after being designated a sexually violent predator, he was transferred to the locked facilities of Coalinga State Hospital. His treatment team there says that in recent years, Stobaugh has willingly submitted to treatment and, having served his full prison sentence, he is now appropriate for highly supervised released.

But there has been significant public outrage — along with official statements of opposition from Sheriff William Honsal and the Humboldt County Board of Supervisors — to a proposal that would place Stobaugh in a house on the outskirts of Manila.

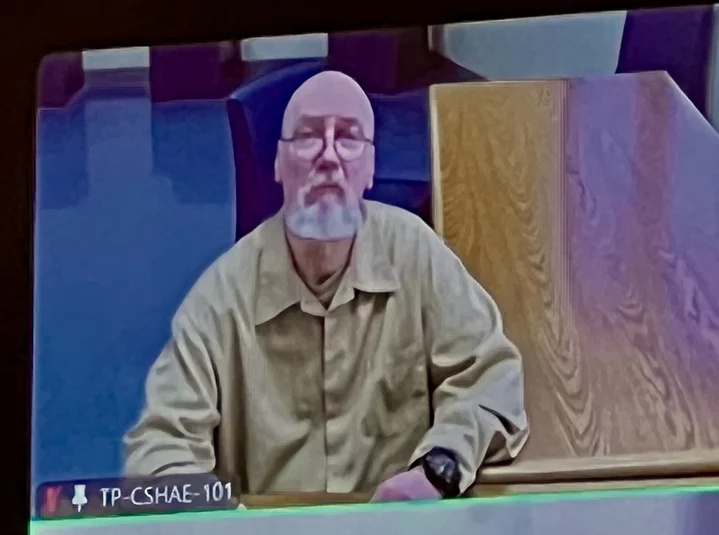

Stobaugh, now a senior citizen, appeared today via Zoom on a wall-mounted TV in the courtroom wearing a long-sleeved, collared tan shirt with matching pants. During the proceedings he occasionally wrote down notes, but mostly he was attentive to the witnesses, who testified remotely via Zoom.

At the end of today’s evidentiary hearing, Timm urged Judge Cockrum to deny Stobaugh’s release while Brownfield argued that the defendant has changed and should be granted released per the recommendations of his treatment team.

Cockrum took the matter under submission and said he’ll likely issue a ruling on the matter tomorrow (Wednesday) morning.

Stobaugh appearing via Zoom on the courtroom TV screen. | Photo by Ryan Hutson.

###

At the outset of today’s hearing, Cockrum explained that since Stobaugh has served the entirety of his prison sentence and been recommended for release, the burden lies on prosecutors to show by “a preponderance of the evidence” that his release would be inappropriate.

Timm’s first witness, sworn peace officer Gerardo Paredes, testified that as part of a special search team at Coalinga, he helped conduct a search of Stobaugh’s four-man dorm room on April 6, 2018. The search uncovered three portable DVD players, a projector and a hard drive. The serial numbers on the DVD players had been scratched off, which is against the law, Paredes said.

The People’s second witness, Sandy Herr, is a special agent with the California Department of Justice but was employed as a detective at Coalinga in 2018. Two weeks after the contraband was recovered from Stobaugh’s dorm, Herr helped conduct an interview of Stobaugh at his request, she said.

During that interview, Stobaugh was “nervous, shaky and sweaty” as he tried to attribute everything on the confiscated hard drive to another inmate, Robert Abelman, whom he considered his best friend. According to Herr, Stobaugh told the investigators that he expected child pornography to be found on the drive — photos of 16- to 17-year-old girls in a file folder named “J.B.” for “jail bait.” He said Abelman had shown him one of these photos and he offered to provide information about Abelman smuggling methamphetamine into Coalinga.

Herr said Stobaugh’s story changed under questioning that he misrepresented his own criminal history, claiming his youngest victim was 20 years old when in fact she was only 18. As the interview progressed, Stobaugh appeared “nervous, sweating and stuttering,” his face red and twitching, which led Herr to conclude that he wasn’t being forthcoming.

In the interview, Stobaugh said he’d obtained his friend’s hard drive so he could watch movies, but he couldn’t give any examples of movies that would be found on the device, Herr testified. Under further questioning, Stobaugh said the girl in the photo was actually only 14 or 15, not 16 or 17, and that she was nude. Herr said his demeanor changed while describing the photo: He was smiling as if pleased, with a smirk on his face.

On cross-examination, Brownfield asked Herr why she’d never asked Abelman if the hard drive was, in fact, his. She said it was because the item had been found in Stobaugh’s dorm, not in Abelman’s, and because Stobaugh clearly knew what was on it and tried to “manipulate the situation.”

On redirect from Timm, Herr testified that during the investigation with Stobaugh, she offered to go ask Abelman directly if the hard drive was his, which caused Stobaugh to get nervous and say something like, “I just killed myself.” In her estimation, Stobaugh really didn’t want investigators revealing to Abelman what Stobaugh had been telling them.

The People’s third witness was Coalinga peace officer and certified cybercrime examiner Hill Magpayo. He testified about what investigators found on the hard drive through a forensic analysis. There was a folder named “ZZZ Rick’s folder,” and Magpayo said “Rick” was Stobaugh’s nickname.

In a folder named “Personal Stuff,” investigators found a sub-folder named “My Movies” that contained a 12-minute video showing a Caucasian girl, roughly 10-14 years old sitting on a patio. The video starts out with her fully clothed but proceeds to depict her orally copulating with an adult man who then engages in vaginal sex with her, Magpayo said.

Another sub-folder, labeled “Pictures,” held photos of an Asian girl, age 12-14, laying on a bed masturbating. Forensic search tools eventually discovered “several thousand” photos of various children, some engaging in sex acts while others were merely “erotic” images of naked or partially naked kids, Magpayo testified.

He also said that Abelman was willing to testify that the hard drive was his but that he (Abelman) didn’t believe there was any child pornography on it.

Both Magpayo and Herr had trouble remembering many of the details of these incidents, some of which occurred more than seven years ago, and Timm often had to prompt them to refer to their reports or to other documents, which resulted in drawn-out and stilted testimony. In one such exchange, Timm asked Magpayo to find a spot in an interview transcript where Stobaugh said Abelman was running a business in the hospital, operating a drug trade and selling other contraband to fellow confined patients.

Later, Magpayo testified that, according to Stobaugh, Abelman had an electronic tablet that he’d “jailbroken” to gain access to the internet via WiFi. Stobaugh admitted to showing photos on the tablet to other patients and Coalinga, who said that the images didn’t look legal, according to Magpayo.

The dorm room search in 2018 also turned up handwritten papers that looked like “payo” sheets — a ledger of debts for contraband, complete with emails and bank account numbers. Timm displayed a copy of the document on Zoom via a courtroom camera.

Magpayo said that Abelman had the nickname “Mickey” in the hospital, and there was a notation on this paperwork saying “Mick-Rick 2018.” Notes of apparent transactions referenced photo trades, and one mentioned “bisexual trades.”

Other notes contained technical details about computer programs and operating systems, including Linux and Android. Magpayo said Linux is sometimes used in criminal activity, but he had difficulty explaining specifics. (At one point, Judge Cockrum sustained an objection from Brownfield about this testimony, noting that Magpayo apparently “doesn’t understand the difference between an operating system and a program.”)

Recovered photos of child pornography were sent to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC), where the images were matched to two known victims.

Public Defender Luke Brownfield (left), Judge Kaleb Cockrum and Senior Deputy District Attorney Whitney Timm. | Photos by Ryan Hutson.

###

At several points during today’s hearing, Timm and Brownfield both asked witnesses about the apparent communication breakdown between law enforcement investigators and the medical treatment team at Coalinga State Hospital, as well as the Humboldt County District Attorney’s Office, which didn’t learn of Stobaugh’s possession of child pornography until fairly recently.

On cross-examination of Magpayo, Brownfield asked whether the handwritten transaction log could have documented bartering of legal items such as food, and Magpayo admitted that it could. He also admitted that he never interviewed Abelman, saying there was no reason to since the contraband had been found in Stobaugh’s room, though the hard drive contained some of Abelman’s documents, including legal materials and personal correspondence.

Stobaugh told investigators that he never personally accessed files containing child pornography, and the investigators found no child porn in the folder labeled “Rick’s stuff.”

Brownfield suggested that some of the images that were supposedly of an Asian minor may in fact have been photos of Abelman’s girlfriend at the time, who was a college-aged Asian woman.

After a lunch break, the court heard testimony from clinical psychologist Dr. Paul Murdock, who conducted annual evaluations of Stobaugh for many years, and Dr. Robert Cureton, clinical director of the conditional release program (CONREP) for sexually violent predators at Liberty Healthcare, the agency that will be charged with monitoring Stobaugh should he be granted release.

Timm pressured both doctors on whether the testimony they’d heard today, or any of the facts regarding Stobaugh’s possession of child pornography and his failure to disclose it, gave them pause or made them reconsider their recommendation to release him to the community under supervision.

Dr. Murdock said he has consistently diagnosed Stobaugh with an other specified paraphilic disorder (a type of recurring, intense and atypical sexual arousal), substance use disorder and antisocial personality disorder, and he said Stobaugh remains a sexually violent predator.

But he said Stobaugh’s possession of child pornography in 2018 doesn’t change his risk assessment, which is based on something called a Static-99R, a widely used risk prediction instrument that estimates the probability of reoffending among adult males with a history of sexual crimes.

Murdock said Stobaugh’s Static-99R score is a 1, but even if it was upgraded to a 2, that’s the level given to common sex offenders who are routinely granted release after serving their sentences. Murdock also said there’s no evidence that Stobaugh is sexually attracted to children, though he may have used child porn as a commodity in the hospital.

Timm pushed back on this, noting incidents from Stobaugh’s criminal past in which he sexually assaulted women with children nearby, seemingly using the kids as a means of control. And she asked Murdock whether he considers children depicted in child porn victims, to which he said yes.

But Murdock stood by his professional opinion, saying Stobaugh has willingly engaged in treatment for years now and evidence shows that there’s a steep drop in rates of reoffending once men become elderly.

Dr. Cureton likewise stood by his opinion that Stobaugh can be safely released under strict supervision, which includes monitoring through a GPS-enabled ankle bracelet, random drug testing, regular polygraph testing, computer monitoring, intensive psychotherapy and direct supervision — tools that “are designed to keep the community safe and to make sure that the person is progressing successfully.”

Today’s hearing occurred because the prosecution asked the court to reconsider its order granting Stobaugh’s conditional release, and Cockrum explained that due to the “liberty interest” that has already been granted to Stobaugh, the D.A.’s office bore the burden of proof.

Timm proceeded to argue that she had met that burden by showing that Stobaugh still displays risky, manipulative and deceitful behaviors, and that, through his possession of child porn, he was still victimizing people. She said that there’s no sign that his “selfishness and criminality” will change if he’s released.

“He is deceptive by nature,” Timm said. “He is a predator, and that’s exactly what Dr Murdock said that he is. But they’re not doing anything to adequately supervise him.”

Brownfield countered that the experts are considered experts for a reason, and they’ve given their opinions that he’s now appropriate for release, having passed every polygraph and done everything required of him since 2019. Brownfield said the allegation of child porn possession hasn’t been definitively proven, and even if it had, that was seven years ago and his doctors testified that he has changed.

Cockrum took the matter under submission and said he expects to announce his decision in the morning. Check back tomorrow for more coverage of this case.

CLICK TO MANAGE