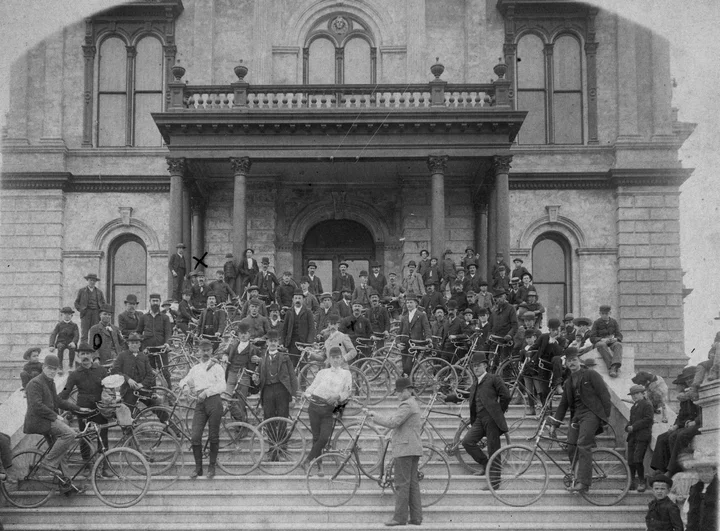

Humboldt Wheelmen gather on the steps of the old courthouse, facing 5th Street, circa 1895. Photos via the Humboldt Historian.

###

ED. NOTE: Suzanne Forsyth, former editor of the Humboldt Historian, was delighted to find herself channeling the pseudonymous voice of “Louella Parsnips” —an ill-reputed, scandal-hungry gossip monger who right-thinking society people publicly abjure — for these pieces of true history.

###

Would Amelia Bloomer, founder and editor of the first women’s magazine, The Lily, be disappointed to know that the thing for which she is most remembered is a pair of women’s undergarments? I very much doubt it. This suffragist and advocate of women’s dress reform herself adopted and advocated the revolutionary outfit of a loose fitting top (no corset) and short skirt with pants underneath in the early 1850s. The style, named bloomers in her honor, was intensely ridiculed and failed to catch on. Indeed, Bloomer was in advance of her time by about forty years. It was not until the 1890s that women could wear bloomers, or knickerbockers, with some degree of acceptance, and that was due to a movement entirely outside of women’s dress reform: the world-wide phenomenon of the great bicycle craze.

It was the gay nineties, and a major contributor to the gaiety was the newly comfortable and affordable instrument of liberation, the bicycle. With the invention of the pneumatic tire in 1888, and the creation of a machine called the “Safety,” with wheels of equal size, suddenly anyone could learn to ride without undue risk or discomfort, and everyone was jumping aboard. Over two million bicycles were sold in the United States in 1897 alone. That is approximately one for every thirty inhabitants, and the good people of Humboldt were as bicycle-crazy as in any place in the nation.

By 1895, downtown Eureka was absolutely teeming with bicycles. Everyone who was anyone was riding a bicycle, and just where were they riding them? Not on the bumpy unpaved streets, you can be sure, not with Eureka’s beautiful network of twelve-foot-wide wooden sidewalks just waiting to be utilized as deluxe bicycle thoroughfares. As my man about town recalls, “Bicycles on the sidewalks in Eureka were as numerous as autos in a wrecking station.” (1)

On one occasion, while wheeling happily along Third Street on his new Rambler, purchased at Ayers Fashion Stables and Cyclery, my man reports witnessing pedestrians “getting pushed aside and forced into the gutters” by the throngs of bicyclists flying down the sidewalks. City ordinances began to be passed, first for bicycle bells to warn pedestrians, and then for bicycle lights at night. Even so, pedestrian injuries remained high. Finally the city fathers passed a revolutionary ordinance “forbidding any bicycles to be ridden on sidewalks in the business district,” (2) with the boundaries being K Street on the East and Fifth Street on the south. This dreadful ordinance met with almost universal opposition, and no one abided by it.

I generally refrain from naming judges in my gossip column, for obvious reasons, but today I make an exception. As it happens, Judge C. J. Stafford was mayor of Eureka at this time. He became so concerned about this matter of everybody violating the ordinance against riding on the sidewalks that he introduced it for discussion at a January 1895 council meeting at which many spectators were present. In his eloquent speech, he asked for the assistance of each and every person present to help enforce the bicycle ordinance.

And he was taken at his word. I am sorry to have to say that the very next day, Judge Stafford himself was apprehended in the act of serenely riding his bicycle along a downtown sidewalk.

It was Lawrence F. Puter and Sam I. Allard who captured the judge in flagrante delicto.

“It was such a huge joke to the two,” recalls my informant, “that they hauled Judge Stafford before Police Judge J. M. Melendy, who assessed the chief officer of the city with a fine of ten dollars for the infraction.” (3)

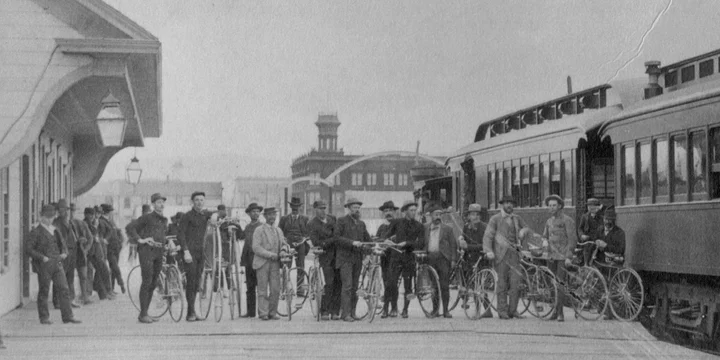

Bicyclists pose for a photograph at the Eureka train depot. Note the high wheelers, also called ordinaries, second and third from left. The cupola of the Grand Hotel is seen in the background, and in front of it the archway for streetlights at Second and A streets.

Of course, every downtown business sported a bike rack for its customers, and every enterprising business proprietor in town wanted to get in on the rip-roaring bicycle business. Shops heretofore proudly selling groceries and dry goods now began advertising as bicycle dealers, mentioning their original merchandise only as an afterthought. For example, consider the grocer A. Cottrell, at the corner of Fifth and H Streets. He placed newspaper ads featuring the “Defiance Bicycle” in large bold letters, while noting in tiny print at the end, “I still continue to furnish groceries to my customers as usual.” (4) One afternoon in 1896, while pedaling through Eureka, my man about town and I counted sixteen establishments where bicycles could be purchased.

Indoor bicycle riding arenas and lessons were another distinctive feature of the day. L. L. Ayers Fashion Livery Stables at 4th and G Streets added Cyclery to its name in 1895, and began the “Ayers Cycling Academy,” with newspaper ads by Ayers reading:

Mine is the largest, best ventilated hall in town. I give personal instruction and have competent help. 50 cents an hour. Engagement made to suit convenience of ladies. Electric light at night … Ladies’ Parlor entrance on G St.

During the early years of the bicycle, the idea of women riding bicycles had been denounced as improper and even immoral, and those who did so were condemned as such, but by the mid-1890s, the immense popularity of the bicycle among both men and women was such that popular sentiment could not but follow along. It was the era of the new woman, and it was women, indeed, who had the most to gain from the great bicycle craze. As they took en masse to their wheels, which required them to be able to breathe deeply and also to enjoy some unrestricted movement of the legs, the impediments of corsets and voluminous floor-length skirts were flung aside — though not everybody was happy about it, as depicted in the 1890s sketch at right. A woman’s ability to go out on her own, under her own power, choosing her own destination, increased both vitality and confidence and widened a woman’s world. As Susan B. Anthony famously stated in 1896: “The bicycle has done more for the emancipation of women than anything else in the world.”

Of course, bicycling revolutionized courtship, too. For one thing, when women began to travel afield on their bicycles, they necessarily had to leave their chaperones behind — “a most agreeable development!” according to my man about town.

“A Bicycle Built for Two” was the most popular song in the country in 1892, and by the mid-nineties tandem bicycles were a feature of the local dating scene. On April 27, 1895, the Arcata correspondent for the Blue Lake Advocate reveals:

The first tandem or “bicycle built for two” ever seen in Arcata was ridden around the bay last Saturday by Mr. Vidy and Miss Edwards of Eureka. They came up in an hour and seven minutes and back in one hour and fifteen minutes. (5)

This timetable would have interested many readers, and all would have pricked up their ears at the indication of a new romance. The following year the same correspondent prints this teaser, “I see my worthy friend Charlie Devander rides a tandem, and of course Charlie don’t ride it alone.”

Not every swain could avail himself of a bicycle built for two, though, and in such cases many a gallant beau would ferry his girl on the handlebars — though perhaps not every couple executed this mode of conveyance in the manner of my man about town and his energetic inamorata. In his own words:

Miss D seemed to enjoy riding on the handlebars, so we developed a method of boarding the bike while in motion. Miss D became adept at coordinating her footwork to the speed of the bike and had no difficulty “coming aboard” and we were off on a tour to Sequoia Park. (6)

But perhaps the most well-known “bicycle built for two” of the late 1890s belonged to the prominent Eureka octogenarian, Rev. C. A. Huntington. This was a vehicle built not for romance but for practicality. The reverend’s great-grandson, Col. Thomas H. Monroe (retired), tells the story best:

Determined as he was to learn to ride a bicycle, he never mastered it. However, the San Francisco Balcom bicycle shop solved his problem by framing two ladies’ bicycles together in parallel. This contraption proved to be rather awkward, and definitely hard to ride, especially for his young grandsons, Tom, Joseph, and McDougall Monroe. One or the other would always be drafted to ride with the old gentleman, who would urge the child to greater efforts by saying, “Push, push harder on the pedals! (7)

The Reverend C. A. Huntington, with the aid of a youthful pedaling partner—one of his grandsons—enjoys a tandem ride along the wide Eureka sidewalks, late 1890s.

Bicycle clubs called the Wheelmen sprang up all across the nation. The Humboldt Wheelmen had clubs in Eureka and Arcata, and they organized cycling tours and picnics every Sunday. Captain of the Eureka Wheelmen Willard Wells routinely led Sunday tours of twenty–five to thirty miles to the Mad River, Hookton, Table Bluff, Southern Humboldt, Salmon Creek, Essex and Korbel.

Local historian Barbara Canepa Saul writes:

The Tour of the Unknown Coast bicycle tour may have had its origins in September of 1895, when it was reported that “Wheelmen Soule, Wells, Janssen, and Littlefield of Eureka arrived in that city last Saturday from their trip ‘around the block’ via Petrolia, Shelter Cove, Garberville and Scotia, the distance traveled from the time they left Swauger was 192 miles.” (8)

Nor were Humboldt women to be left behind: a July 1895 article in the Enterprise reads, “A number of young ladies in Eureka are organizing a bicycle club similar to those of the men. They will adopt a distinctive name and costume, indulge in road runs and sociables in every way.” (9)

Arcata women also formed a club: “The Arcata cycling club expects to take a run to the mouth of Mad River next Sunday. The Ladies Annex of the club will also join. A commissary wagon will be a feature of the run and a good time is anticipated by the participants.” (10)

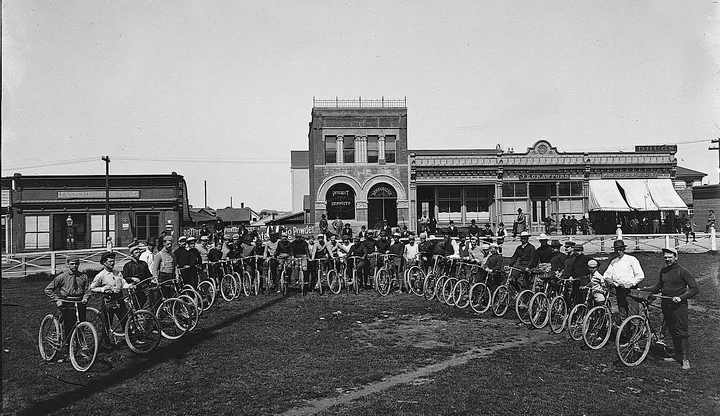

The Arcata Bicycle club, formed in 1896, on the west side of the Arcata Plaza, in a photo by A.W. Ericson.

Trips between Eureka and Arcata were common in both directions. A newspaper entry in the Susie Baker Fountain Papers states that the Eureka Wheelmen rode to Arcata on Sunday mornings and circled the Plaza, executing “a well-learned drill,” which may have consisted of formations and possibly even bike tricks, as one Wheelman, Rodney Burns, was said to be proficient in trick-riding and “antics.”

An important activity of the bicycle clubs was improving the roads, and benefit dances and other fundraising activities were always on the calendar. An August 1, 1896 newspaper announcement reads:

Eureka is preparing to wet the road toward Arcata, and tanks are being erected by the roadside for the sprinkler. The Arcata cycling club will give a good-road dance at Arcata Hall next Tuesday evening to raise money to sprinkle public roads. (11)

It is a wonder and a delight to recall, as revealed in an 1896 Munsey’s Magazine, that at one time “rapid transit” was envisioned as “elevated bicycle paths.” It didn’t happen. The Gay Nineties gave way to the new century. The Wheelmen’s improved roads were taken over by a new must-have, the automobile — “even better for courtship!” declares my man about town. By 1913, Eureka’s bike racks had disappeared, and only one store continued to sell bicycles. Automobile-related businesses, however, were thriving.

NOTES

- Humboldt Times, February 12, 1931 “Old Timer! Do You Remember When …” by Will Speegle.

- Ibid.

- Ibid; Ferndale Enterprise, January 1895.

- Daily Humboldt Times, March 26, 1896.

- Blue Lake Advocate, April 27, 1895.

- “Bike Riding Memories,” The Way it Was, edited by Gayle Karshner, 1973, vol 2, p. 8.

- Humboldt Historian, September-October 1974.

- Humboldt Historian, 1998.

- Ferndale Enterprise, July 1895; Humboldt Historian, September-October 1988.

- Blue Lake Advocate, June 6, 1896.

- Susie Baker Fountain Papers.

###

The story above was originally printed in the Winter 2013 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE