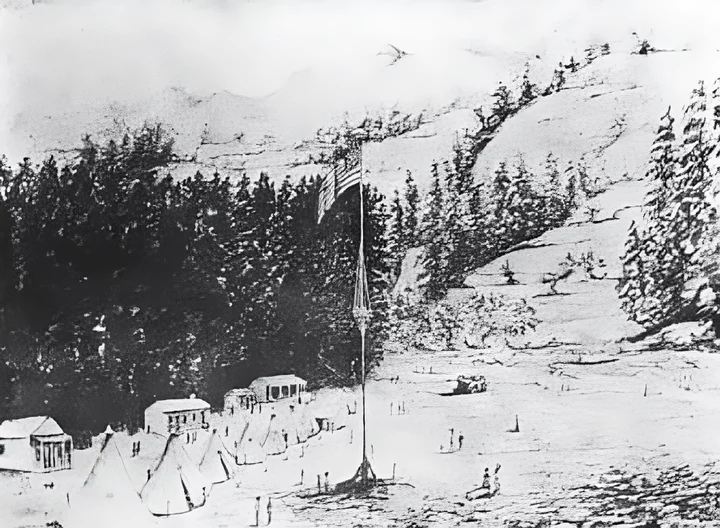

Sketch of Fort Ter-waw, via the Library of Congress.

###

PREVIOUSLY:

###

A complex pattern of displacement and genocide ravaged indigenous communities across the American West through the 1860s. Weaving together Native American voices, government reports, and settler perspectives, a cohesive narrative of this dark chapter in Humboldt’s history can be revealed.

In the days after the Wiyot Massacre, about three hundred Native Americans were congregated at Fort Humboldt.1 In regions not targeted in the slaughter, such as Mad River (Baduwa’t), Wiyot people continued to inhabit their homes. Agent D. E. Buell came to Arcata in April 1860, where he advocated for the removal of the Wiyot to the Klamath Reservation. Buell invited Baduwa’t leaders to Arcata for a meeting and announced plans for their expulsion:

After urging countless objections against leaving their old homes, and fears for their welfare on the reservation, [the Wiyot] said that they thought they would go, but wanted a little time — two or three days — to make ready. To all this they were answered by the agent and citizens, that if they did not consent to remove, force would be used to compel them; that should any of them succeed in eluding the agent and… [the citizens] at this time, they would henceforth be treated as enemies; that before sunset every Lower-Mad River Indian must be in town ready to start the next morning for the Klamath; that some of the party present were to remain in town while the others would accompany white men to the different camps and rancherias to bring in the balance of the Indians, and that there was to be no more talk on the subject.2

Faced with an impossible choice, Baduwa’t communities collected what they could carry, setting their canoes and homes on fire as they left so that they would not be appropriated by the settlers.3At 4 p.m. that day, the Wiyot gathered in the center of Arcata for the forced removal to Klamath Reservation. Buell then fixed his sights on the Wiyot people who were located at Fort Humboldt. Commanding officer Gabriel J. Rains initially appeared to defend the rights of the Wiyot, but quickly caved to public opinion at the urging of eighty-four settlers.4 Nearly 450 people were removed from Humboldt County to the Klamath Reservation.

Jane Searson, a 20-year-old Wiyot survivor, recalled jarring details of the forced march:

I remember about 300 Indians coming back have clothes, they [were] driving the Indian like cattle… [swing] whip like drive catt[le] … [Their] legs were [bleeding] and cut [by] the [whip.] They passed dow[n] the road and I had a good look and seen how th[e]y [were] treate[d]. They were on their way to the Res. They [were] to take my child away if I did not go.5

Using physical violence, Lieutenant Hardcastle of Fort Humboldt pushed the victims along rugged backcountry trails at breakneck speeds. Roughly a third of the Wiyot — the sick, young, and elderly — were brought to the point of complete exhaustion.6 The number of deaths resulting from this march remains unknown. It should be recognized that not all Wiyot were taken to the reservation: in some cases, people remained in Humboldt as a result of settler marriages and indenture contracts, while others lived in the rural countryside with hopes of avoiding further persecution.7 Practically every path taken by Native Americans during this period risked violence or death.

For a brief time the expelled Wiyot lived near the mouth of the Klamath River near a place called Wau-Kell, the reservation headquarters.8 People were divided into small villages with eight to twelve acres of farmland. Through these farm communes the Bureau of Indian Affairs intended to disrupt hunter-gatherer methods and replace them with agrarian practices.9

Forcibly relocated away from their homes under false promises of “protection,” the Wiyot could not escape the terrible cycle of violence. The source of this abuse was the military personnel of Fort Ter-Waw, located across the river from Wau-Kell.10 One historian states that those who were detained at Klamath were “continually exposed to the brutal assault of drunken and lawless white men; [the women were] forced, and, if resented, the Indians [were] beaten and shot.”11 Oral accounts affirm that a gallows was built between two redwood trees near the fort and used to hang Native Americans, possibly to execute those who resisted forced agricultural practices.

Inadequate harvests and widespread malnourishment made conditions even worse.12 In contemporary accounts, the Tolowa have compared the Klamath Reservation to a concentration camp. Indigenous people seized the earliest opportunities to escape the abysmal state of affairs at Wau-Kell. In July 1860, the Humboldt Times stated that the Wiyot were returning to Humboldt Bay, and by the fall of that year “nearly all of the Indians removed to Klamath last spring [had] returned.”13 Hundreds of expelled people made the long march home with hopes of returning to the villages that their families had inhabited since time immemorial. Soon after their arrival, however, a renewed expulsion campaign was carried out upon Wiyot communities.

By October 1860, citizens began petitioning for a second removal of returning Native Americans.14 Settlers took the matter of deportation into their own hands. In Hydesville, a public meeting was held with the goals of “[making] arrangements in relation to the Indians of [Humboldt] county…”15 Attendees resolved that all Native Americans were to be rounded up and removed to the Klamath Reservation, except for those under the age of ten who were the servants of white households for at least a year, or if they were born outside the county. Vigilantes went door to door, visiting settler households and demanding that they “provide a way and means to send [Indians] to the Reservation.”16 Among the men involved in the plan were Sheriff Van Nest, George Huestis (nephew of the county judge), and suspected massacre culprit Hank Larrabee.17

By September 1861, several hundred Wiyot were forcibly congregated at Fort Humboldt through the posse’s efforts. In cooperation with Agent Buell and Colonel Lippitt (commanding officer of Fort Humboldt), Captain H. H. Buhne assumed the role of transferring the Wiyot back to the Klamath Reservation aboard his steamer, the Mary Ann. 18 Those aboard the Mary Ann arrived at an unfortunate time: an extreme winter storm battered the Northern Californian coast between December 1861 and February 1862.19 The Humboldt Times on January 25, 1862 wrote, “The [Klamath] Reservation has been inundated five several times since the first of last month, and at each overflow the Klamath rose higher by many feet than any Indian tradition gives account of.”20 One individual observed the churning Klamath River swell 150 feet above its average height, while a Yurok elder suggested that it was the worst flood in living memory.21 Due to its low-lying situation, Wau-Kell was doomed by the rising floodwaters.

“[E]very panel of fencing, every Indian village, and every government building, except a barn” had been swept away by the destructive flood.22 To make matters worse, one of the few redeeming factors of the reservation — its fertile topsoil — was now covered in a deep layer of silt, preventing farming for many years to come.23 The agency’s entire food reserve was destroyed, leaving two thousand Native American people on the verge of starvation in the middle of a winter storm.24 An immediate evacuation was necessary. Superintendent Hanson wrote, “[Native Americans] will either perish for lack of food or return to their old [homes] … [where they will begin] depredations on the settlers’ [live]stock, which they must do from necessity or die. ”25 By the time he made these remarks, hundreds of people were already returning to their ancestral lands throughout Humboldt County.

The Wiyot expulsion to the Klamath Reservation was a catastrophic failure of the federal government on both a moral and logistical scale. The 1861-62 Flood worsened an already awful situation, sparking a humanitarian crisis and mass exodus. As hundreds of starving, displaced people fled the reservation, they returned to Humboldt not as refugees in need of help, but instead as enemies who the settler community actively hunted and killed. This period marked the final phase of the so-called Humboldt Indian “Wars,” in which Native Americans were targets of an atrocious campaign of genocide. Yet these tales of persecution remain unspoken, nearly forgotten by time — perhaps this morbid chapter in our local history has been deliberately hidden by Humboldt’s founding pioneers, the very people who carried out this butchery.

###

Ryan Bass is a historian of Yurok-Karuk descent at Cal Poly Humboldt. After receiving the Charles R. Barnum Award for his research on the 1964 Flood and its effects on indigenous communities in Humboldt-Del Norte, he has shifted his research focus to two particular topics: the Hoopa Valley Boarding School (1892-1932) and the California Genocide (1849-1873). Published works regarding these topics are expected to be released later this year.

You like history? Consider a subscription to the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

###

1 Edwin Bearss, “The Klamath River Reservation,” in Redwood National Park History Basic Data , 105-112; Humboldt Times, April 14, 1860; Bledsoe, Indian Wars of the Northwest, 320, 322.

2 Northern Californian, April 18, 1860.

3 San Francisco Bulletin, May 11, 1860.

4 Heizer ed., The Destruction of California Indians, 160-161; Secrest, When the Great Spirit Died, 331-332. Humboldt Times, April 14, 1860; Bearss, “The Klamath River Reservation,” 105-112.

5 Bearss, “The Klamath River Reservation,” 105-112.

6 Jerry Rohde ed., Statement from Jane Searson, Wiyot History Papers (Cal Poly Humboldt Digital Commons, 2014). I want to acknowledge the frequent use of brackets in this quote: the original text contains numerous grammatical errors, certainly due to the fact that many Wiyot did not speak, read, or write English as a first language. Brackets were applied to aid in the interpretation of Jane Searson’s shocking testimony.

7 Magliari, “Masters, Apprentices, and Kidnappers: Indian Servitude and Slave Trafficking in Humboldt County, 1860-1863,” California History 97, no. 2 (2020): 2-26; Olive Davis, Genealogy and Stories of Arnold Call Spear (Self-published, 1977), 2, 25-28; Denis Edeline, At the Banks of the Eel (Self-published, 1978), 7.

8 Bearss, “The Klamath River Reservation,” in Redwood National Park History Basic Data, 105-112.

9 Madley, An American Genocide, 261.

10 Humboldt Times, November 24, 1860, January 5, 1861.

11 Humboldt Times, July 28, 1860.

12 Humboldt Times, October 6, October 13, 1860.

13 Susie Baker Fountain Papers, Volume 34, 542; Humboldt Times, October 12, 1861.

14 Susie Baker Fountain Papers, Volume 34, 542.

15 Magliari, “Masters, Apprentices, and Kidnappers,” 20.

16 Humboldt Times, September 14, 21, 1861.

17 Bearss, “The Army and the Klamath River Reservation,” Part D, in History Basic Data, 85-102.

18 Humboldt Times, January 25, 1862.

19 The War of the Rebellion, Volume 50, Part 1, 906.

20 Bearss, “The Klamath River Reservation,” 105-112.

21 Humboldt Times, January 25, 1862.

22 Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs for the Year 1862, 313-314.

23 Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs for the Year 1862, 314.

24 Rogers, “Early Military Posts of Del Norte County,” California Historical Society Quarterly 26, no. 1 (1947): 3-4.

25 Smith River Rancheria Archive (Arcata, CA: Library Special Collections & Archives, 2002), Al Logan Slagle ed., The Tolowa Nation of Indians, “History Through 1906,” 71-83.

CLICK TO MANAGE