As a person approaching his 91st birthday who has been keeping abreast of present day transportation problems, I find an irresistible urge to compare today’s methods of getting from here to there to those of an era of some 80 years past.

A comparison that comes to mind is the trips that my mother made to visit her parents, who resided in Eureka, Calif.

My grandparents were Will and Laura Davis. Granddad worked for Hammond Lumber Co. as a woods filer. He retired in 1930.

My parents. Bill and Lucy Hinds, and I lived in McCloud, Calif., where my dad was plant superintendent.

To set the scene properly, McCloud lies approximately 120 airline miles from Eureka at the foot of Mt. Shasta. Today, that would be two hours travel time by air. In 1905, to my knowledge there wasn’t a single foot of paved or oiled road in Northern California. In winter, most roads would be impassable.

To get anywhere with any degree of certainty, you had two choices: the train or by steamship, both of which were considered to be fairly reliable for the times.

In Mother’s case, she relied on both the train and steamer plus city streetcars and horse-drawn hacks to get herself and a young son from McCloud via San Francisco to Eureka and return. A trip of some 80 odd hours one way if the trains were running on time and steamship schedules hadn’t been fouled up by storms or fog.

If one were forced by circumstances to attempt the trip over the mountains by roads and trails then available, one could safely figure weeks on the trail and a great many hardships to boot.

Mother always looked forward to these yearly trips, though not a Eureka girl. She had many friends there and her sister, Oma Lautin, lived on E Street. Oma and her husband, Sig Lautin, owned and operated a store on Second Street that sold clothing to woods’ personnel.

Though I had made the trip several times as a baby, the first recollections I have are about age four. My mother, by that time, was a seasoned traveler — at least by that route — so things were usually routine.

We would leave in the month of June when the deep snows were gone in the Siskiyou mountains. My dad couldn’t make the trip as mid-year was the busy time for him.

He would drive us to the McCloud River Railroad Station and we would take the afternoon train to Sisson (Mt. Shasta) arriving at 4:30. The Shasta Limited of the Southern Pacific Railroad was due at 5:30 p.m. and was usually on time.

The Shasta was one of the S.P.’s top trains. It would be made up of several Pullmans, a diner, one or two coaches, and several mail and baggage cars.

Postcard of the Shasta Limited stopping over at Shasta Springs. Public domain.

As a four-year-old and later at six, these trips were wondrous experiences. Even later, at the ripe old age of 10, I never lost my awe of the monstrous consolidated locomotives, the gleaming varnish of the Pullmans, the polite and efficient porters, the authoritative train conductor and that never-to-be forgotten dining car with its snowy white table napery and shining silverware. I remember, too, the smart steward, sure-handed efficient waiters and the excellent menus by some of the best chefs to be had anywhere.

Sisson (Mt. Shasta City) was only a short stop for the Shasta Ltd. and we had hardly found our Pullman section when we were on our way.

Mother always reserved a full section, which gave us an upper and lower berth with much more privacy. Trains in those days were usually booked solid and Mother would make her reservation well ahead of time. There would be one other short stop at Shasta Springs to allow the passengers to sample the soda water. At that time it lived up to its reputation — sharp, cold, clear and a wonderful mix for almost any drink (today it is polluted and undrinkable).

After Shasta Springs, the division stop at Dunsmuir was where engine crews were changed. Then came the long, non-stop drop down the Sacramento River Canyon to the valley floor. Soon after leaving Dunsmuir, the first call for dinner would be announced by a waiter ringing soft chimes.

By this time. Mother had made herself presentable and managed to get me in some sort of order so we could make our way to the diner.

This could be quite a trip in itself. If our car happened to be well back in the train, one would have to pass inspection by several cars of people. Mother was a very dignified lady and would take it all in stride.

The steward would meet us in the foyer and escort us to a table with a flourish—seat Mother and hand us the menus on which were so many choices that I had a hard time making a decision. However, I would wind up with breaded veal and Mother always had the S.P. salad (for which it was famous). I would have a dessert and Mother, her black coffee. The waiter offered finger bowls and the check. We had dined in style for $1.50, to which Mother added a tip of 25 cents.

By the time we had finished dinner, it would be dark and when we returned to our Pullman, we’d find the porter starting to make up berths. The intricacies of the Pullman berth of the period and the ease with which the Pullman porters solved the problems of assembly and were able to come up with a fairly comfortable individual bedroom in a short period of time was, to me, an engineering feat of note.

As I grew older. Mother always made me take the lower berth as she knew I would never get to sleep unless I could watch out the window.

As mentioned before, from Dunsmuir to the head of the Sacramento Valley at Redding, the train was non-stop. The S.P. tracks followed the river at the bottom of the canyon so there wasn’t much to see at night. In later years, when the Shasta dam was built, the tracks were forced to higher elevations and were much more scenic.

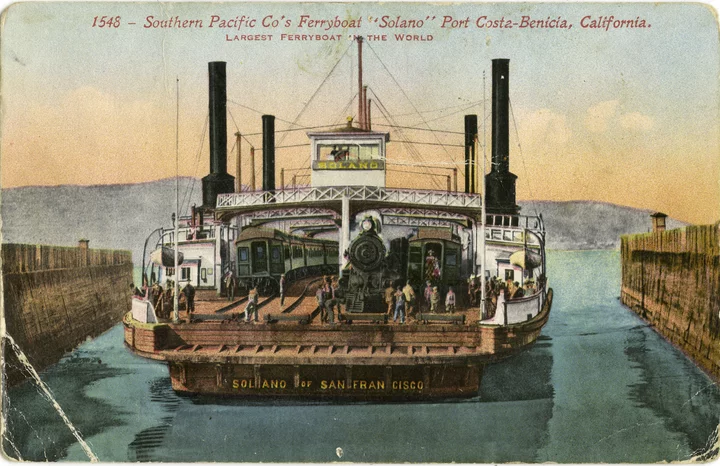

After the stop at Redding, sometime around midnight, the Limited rolled down the valley with very few slowdowns but I knew when we were passing through a town by the ringing of the crossing bells: Anderson, Red Bluff, Corning, Orland, Willows, Maxwell, Williams, Arbuckle, Woodland, Davis, Dixon, Fairfield, Cordelia and finally, in the early morning, the highlight of the train trip — Benicia and the transfer of the entire train onto the car ferry Solano, from Benicia to Martinez across the Straits in one trip.

A postcard featuring the Solano ferry preparing to cross the straits. Uploaded by Arkiv i Nordland from Bodø, Norway - AIN.A15.104.p0040, CC BY 2.0, Link

This ferry was a marvel in itself and was the largest in the world. It was the last word in engineering ingenuity. It worked for many years on the Benicia run without a single failure until replaced by the present drawbridge.

I always awakened when we pulled into the ferry terminal at Benicia and watched the entire proceedings. The train was divided in half and each section switched onto the Solano and tied down as specified by safety rules. Then came the starting of the monster single cylinder engines — one to each 24-foot paddle wheel. It was then up to the pilot to keep the ferry on course by synchronizing the engines.

No one was allowed off the train during the crossing but I managed a good view of the proceedings from the observation car platform.

After the train was remade on the Martinez side and we were on our way again, we would go to the dining car and have breakfast. While putting away some of S.P.’s tasty pancakes, we could enjoy the view of the Emeryville Mud Flats and their accompanying odors.

After pulling out of the 16th Street Station in Oakland, Mother would get our things together for the end of our journey at the “Oakland Mole.” The “Mole” was world famous—the S.P.’s main terminal for trains from the North, East, Mid-West and deep South. At that time Los Angeles was not a terminal, only a station stop on the vast S.P. empire. Trains from New Orleans terminated at the “Mole.”

As the train slowed for the terminal, we would thank our porter and conductor for a pleasant journey. Mother would signal for a Red Cap and we would head for a waiting S.P. ferry. Fifteen minutes after the arrival of the Shasta Limited, we would be crossing San Francisco Bay. We had arrived at approximately 10 a.m.

Crossing the Bay was a thrill for me and I would hurry to the upper deck to watch the Bay traffic. The white paddlewheel ferries of the Southern Pacific—the gold, screw-propelled boats of the Key Route System and various other types of Bay traffic, made the trip an adventure for a small boy.

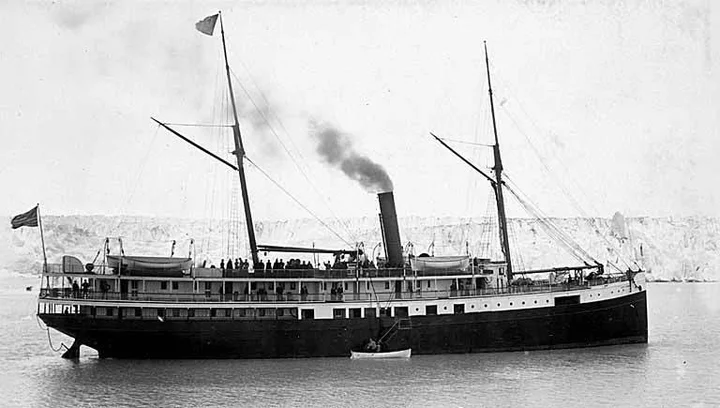

We would arrive at the ferry building at about 10:30 and have almost seven hours to kill before the coastal steamer the City of Topeka, would sail. Mother always chose the Topeka, as Mabel Standley was the stewardess on board.

The City of Topeka beside Muir Glacier in Alaska. Photo: Arthur Churchill Warner. Public domain.

Mabel was one of Mother’s school day classmates at Usal and Greenwood on the Mendocino Coast. They had also attended high school in Ukiah. Mother was born in Ukiah at the home of her grandparents, Jacob and Laura Duncan, on Oak Street. The Standleys also lived in Ukiah.

Will Standley was sheriff of Mendocino County. They later moved to San Francisco where Will was on the police force for many years. There was one other Standley, whom I met a few years later. He was a young ensign just graduated from the Academy and was with the Great White Fleet on its world tour. Hal Standley made it up the ladder to fleet admiral and on his retirement was appointed ambassador to Russia.

If Mother had any shopping to do for the folks in Eureka, she would spend time at Hale Bros., The Emporium, The City of Paris or Roos Bros. We would have lunch at the Golden Pheasant and, about 4:30, we would be aboard the Topeka, which would sail at 5:30. We would get settled in and I could roam the deck and watch the bustle of getting underway for the overnight trip up the coast.

The ship was always full to overflowing with passengers and a berth would be at a premium if not booked well ahead of time. Mable Standley always took care of this problem for Mother.

At this time, the only scheduled run north of San Francisco along the coast was to Eureka by the Pacific Coast Steamship Company, which tried to keep three ships on the run: the Pomona, Corona and the Topeka.

The Pomona and Corona were hard-luck ships and always seemed to be in trouble. The Corona had wrecked on the Humboldt bar the year before and the Pomona found an uncharted rock off Fort Ross. The Topeka was just the opposite. She was in constant service for years from 1905 to 1918. She was sold to Inter-Island Steamship Company and worked in the islands until scrapped in 1935.

I was allowed to roam the deck until we were outside the gate and before the seas became rough. Then I was confined to our cabin or the ship’s salon. The narrow decks of the ship were not safe for a small boy. However, I didn’t lack for entertainment. The Topeka‘s chief engineer was a friend of Mabel’s and he would take me down in the engine room and sit me in a chair where I could watch the big triple expansion engine and the crew in the boiler room as they shoveled coal into the marine boilers. I could never remember the ship’s captain but I never forgot Lars Kennedy, the big chief engineer. (He and Mable both went with the Matson and U.S. lines years later on their runs to Hong Kong and China ports.) I was usually asleep by 9 p.m. I never knew when Mother got to bed as she and Mabel would drink coffee till all hours as they hashed over the whereabouts of old friends.

I always woke in the morning when I felt the ship’s engines go to “slow, ” as the captain got the ship into position to run the bar. As described by Lars, running the bar was a tricky bit as attested by the Corona wreck on the north jetty.

The Humboldt bar didn’t give a ship too much clearance, plus the fact it was always shifting.

The Topeka was smaller by about 300 tons than the other ships of the line, so it had a better chance of getting in okay. What the captain did was wait for a high wave crest, then he would surf in.

When the engine speeded up you knew we were on the wave crest and in we would go. In later years, as better dredges were developed, this hazard was eliminated.

After the bar crossing, we would move sedately up the Bay, serenaded by a few sawmill whistles; then into her dock where about half the population of Eureka stood waiting for friends, freight or mail.

Grandmother Davis and Aunt Oma would be standing on the dock. Then, after gathering our luggage, we would take the California Street trolley to my grandparents’ house on Albee Street and the first half of our trip would be over.

Our stay was usually about two weeks. We would sometimes go out to the camp where granddad worked. This would entail a trip across the Bay, where we took the Hammond Logging train out past Big Lagoon and Trinidad. We would visit for a day or two, then head back to Eureka.

The return trip would be a repetition in reverse. The Topeka would sail on the evening tide and would dock in the city in the morning. We usually spent a couple of days in the city, as Mother would have a lot of shopping to do for friends in McCloud and clothes to buy for the family. Stores in Siskiyou County didn’t have many bargains in those days.

The Shasta Limited pulled out of the Oakland Mole about 8 p.m. and the return trip’s running time was the same though two engines were needed after leaving Redding for the steep grade up the canyon.

It would be well into daylight when we reached Dunsmuir, so I could watch the scenery. But, as it was the country we lived in, nothing new was added.

The Shasta pulled into Sisson at 10:30 a.m. and Dad would meet us as he knew Mother would be loaded down with luggage. After an hour in Sisson having lunch, we loaded aboard the McCloud RR combo and an hour and a half later our trip ended back at McCloud. The last trip my mother and I made to Eureka was 1913. In 1916 my dad and mother moved to San Francisco.

By 1918 the Northwestern Pacific Railroad was completed to Eureka and in operation. By 1924, the road system of the Northern California counties was complete enough so that my grandparents, then more than 80, drove their Chevrolet 490 from Eureka to Sonora, Calif., without incident.

So ended a most interesting era….

Today, one would have a choice of many routes to make the trip from McCloud to Eureka, but he would find it impossible to duplicate the trips my mother made in those early days of this century.

The scheduled steamship runs, up and down the coast, disappeared many years ago and even passenger trains are now hit and miss by Amtrak.

If one is on business and with limited time, one can hop into a Cessna 180 and, in less than two hours, be landing on any one of Humboldt Bay’s area airports, including Murray Field inside Eureka city limits.

By auto you have several routes, all with paved roads — some fast, some scenic. The fastest is 1-5 to Redding, then 299 across the Coast Range direct to Eureka — running time: six hours.

Route 96, through Yreka, Happy Camp, Clear Creek, Weitchpec, Hoopa and Willow Creek, is one of the most scenic in Northern California. Allow eight to 10 hours.

Another interesting route is 36 from Red Bluff through Platina, Wildwood, Forest Glen, Dinsmore and Fortuna. Time: eight hours.

In 1905, all of these land routes were pack trails only. Today, they are all-weather routes except under severe winter storm conditions. Then they may be closed for short periods only.

###

The story above is from the Autumn 1994 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE