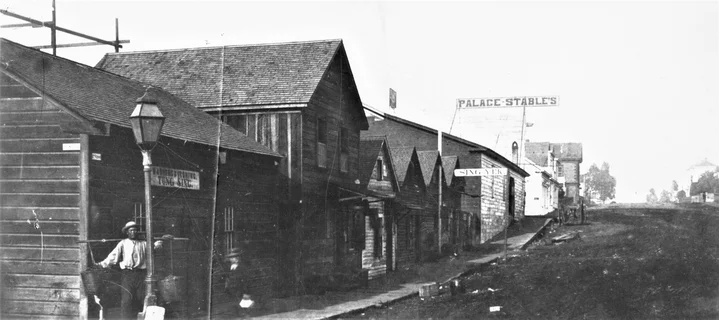

This circa 1884 photo shows the north side of Eureka’s 4th Street, between E and F. Near the middle of the block can be seen the sign for Sing Yek’s store, where the fatal shot was fired on February 6, 1885. The photograph was taken from near the spot where David Kendall was crossing the street when he was shot. (Cal Poly Humboldt Library, Special Collections, 1999.07.3177.) Click to enlarge.

As a historical researcher focusing on Humboldt County’s Chinese history, I was deeply interested to read Shawn Leon’s article “Who Shot David Kendall? 140 Years Later, the Event That Sparked the Chinese Expulsion is Still Shrouded in Mystery” (LoCO, May 3, 2025).

The 1885 Eureka expulsion is a pivotal event in Humboldt history. I applaud Mr. Leon for delving into this important and complicated topic. Leon makes the intriguing point that Eureka’s Chinese community members were probably in the midst of celebrating the festival of the Kitchen God (or “Little New Year”) when the mob violence of the expulsion tore their community apart. As Leon also emphasizes, it is important to study the individual members of Eureka’s “Committee of 15” who directed the expulsion. Such research has the potential to uncover how the characters, politics and beliefs of these 15 men may have helped to shape Humboldt County’s 70-year-long Chinese exclusion policy.

In his article, Leon questions the established account of how Eureka City Councilman David Kendall met his death on the evening of February 6, 1885. Leon suggests that, rather than being the accidental victim of a gunfight between Chinese community members, Kendall was killed by a hidden “clandestine assassin.” Leon further theorizes that this assassination may have been part of a conspiracy involving the Committee of 15 along with civic leaders such as the mayor, the sheriff and the district attorney.

I have spent much of the past two years researching Humboldt’s 19th-century Chinese community, from the 1850s through the mid-1880s expulsions and beyond. Through close reading of local newspapers in online archives and on microfilm, I have encountered many elements of this history which are little-known today. I want to take this opportunity to share some of those discoveries. In particular, I believe that the evidence argues against the “clandestine assassin” theory.

To briefly recap the events of that February night: at 6:05 p.m., David Kendall was shot dead while crossing the street at 4th and E, on the edge of Eureka’s Chinatown. An angry mob soon gathered, blaming the Chinese community for Kendall’s death and threatening to burn Chinatown to the ground. In response, Mayor Thomas Walsh called an emergency public meeting at Centennial Hall, less than a block from Chinatown. At that meeting, 15 prominent citizens were appointed to meet with leaders of the Chinese community and inform them that Eureka’s 300+ Chinese residents had merely 24 hours to pack their belongings and be ready to set out for San Francisco via the two steamships then docked in Humboldt Bay.

In “Who Shot David Kendall?” Leon writes that the Committee of 15 were nominated “to supervise the white mob in carrying out the expulsion … inaugurated and supported by Mayor Walsh, Sheriff T. M. Brown, and District Attorney” George Washington Hunter. Leon interprets the expulsion as follows: “While technically a criminal conspiracy for unlawful detention and abduction, this vigilante justice had the blessing of the Eureka mayor, district attorney and sheriff in a blatant abuse of power.”

I believe this analysis fundamentally misinterprets the interactions of the civic leaders at the February 6 mass meeting, the Committee of 15, and the as-many-as 600 men who attended the meeting.

As word spread through Eureka that Councilman Kendall was dead, Mayor Walsh and his fellow town and county leaders had to be desperately aware that the “thoroughly frenzied crowd” (as described in the Daily Times-Telephone the day after Kendall’s death) could easily become a murderous mob. There was real risk of rioters massacring Chinese residents and possibly setting fire to the town. The Ferndale Enterprise wrote, a week later (Feb. 14, 1885, p. 2):

The anger of the people was worked up to its highest pitch, and it needed but a leader and there would have been committed a fearful massacre … It took much persuasion to restrain them, and as the meeting adjourned it was but the faith in the result of the committee’s mission that prevented them from acting desperately.

Mayor Walsh must have known all-too-well that riot and massacre were horribly likely outcomes. He was almost certainly aware of the infamous Los Angeles Massacre of 1871, when a botched arrest attempt morphed into an orgy of mob violence in which white and Latino townspeople lynched at least 17 Chinese fellow-residents. (This horrific event is explored in depth in The Chinatown War: Chinese Los Angeles and the Massacre of 1871 by Scott Zesch.) A more recent example of mob violence which likely haunted Eureka officials on that February night was the Cincinnati Riot of March 1884, when rioters attacked a jail with the aim of lynching a prisoner, resulting in 56 deaths and more than 300 people injured.

Glimpses of two earlier moments in Mayor Walsh’s career suggest that he had good working relationships with members of Eureka’s Chinese community. On January 28, 1881, when a ban was in place against setting off fireworks in Eureka on any other date than July 4, the Humboldt Times reported, “Mayor Walsh has granted the Chinese of this city permission to discharge fire works in the celebration of their new year,” explaining that “the time embraces twenty-four hours–from this until to-morrow evening.”

The other relevant glimpse of Mayor Walsh’s career was recorded in a Eureka Police Court transcript from a September 1884 trial, The People versus Wah Yee. That transcript itself does not seem to have been preserved in any historical archive, but it was extensively quoted by author Clarence Coogan in an article in his “Paths of the Pioneers” series written in the mid-20th century (Susie Baker Fountain Papers, Vol. 51, p. 335, Humboldt Room, Humboldt County Library). Wah Yee was on trial for making threats against another Chinese Eureka resident. The court interpreter for this trial, known as Ah Kow, testified that he personally had briefly hired local carpenter and handyman Johnny Fox as a special policeman patrolling Chinatown, in response to rising factional tensions in Eureka’s Chinese community.

Ah Kow was quoted as saying, “I hired Johnny Fox myself and paid him two weeks to make it all quiet in China Town. Mr. Walsh (the mayor) he told me I had better do it, and I tried to make every China house pay the money to keep Johnny Fox there all the time.” This mention of Mayor Walsh in Ah Kow’s testimony suggests that Walsh was on good enough terms with some members of Eureka’s Chinese community for that conversation to have taken place.

The Times-Telephone reported that at the mass meeting on the night of Kendall’s death, three men who would shortly be appointed to the Committee of 15 – A. J. Bledsoe, Frank McGowan and James Brown – spoke to the crowd and “dwelt on the evils incident to the hoarding of vicious Chinese in the very heart of our fair town.” In contrast were the next two speakers, Sheriff T. M. Brown and District Attorney Hunter. These two officers of the law, “while sympathizing with the indignation of the audience, counselled moderation” (Daily Times-Telephone, Feb. 7, 1885, p. 2).

The next afternoon, while 300 or so Chinese Eurekans waited under guard in warehouses on the wharf for weather conditions to permit them to sail for San Francisco, Sheriff Brown took an extraordinary action to protect the 21 Chinese men in the jail, ten of whom had been arrested immediately after Kendall’s death. For the first time in Eureka’s history, a law enforcement officer called the National Guard into active service. As reported in the February 14, 1885 Ferndale Enterprise, Sheriff Brown sent the following order:

Commander James T. Keleher, Commander of the Eureka Guards: It appearing to me that an attempt is about to be made to resist the laws of this State on the part of a number of the citizens of Eureka, by taking from me a number of prisoners in my custody, I desire and request you to call into active service the Eureka Guard to aid me in securing the laws and preserving order. Please be at the Court House immediately.

T. M. Brown,

Sheriff of Humboldt County.

The National Guardsmen took up position outside the courthouse, remaining on guard until 10:00 the next morning. By that time the ships had sailed with Eureka’s Chinese community aboard, and Sheriff Brown decided the risk of the jail being stormed by a lynch mob had passed.

I believe the contemporary coverage shows that, rather than being part of a conspiracy to unlawfully evict the Eureka Chinese, officials such as Mayor Walsh and Sheriff Brown worked first and foremost to avert bloodshed, protecting both the Chinese community and the community as a whole.

According to the arguments advanced in “Who Shot David Kendall,” a major point in favor of the clandestine assassin theory is that “There are no known reports of witnesses seeing a gunman, or a suspect fleeing the scene.” This assertion is untrue, as shown by the local newspaper coverage in the months following Kendall’s death.

On February 13, a week after the main expulsion, 16 Chinese men were released from the Humboldt County Jail. They sailed on the regular Saturday steamship for San Francisco. As District Attorney Hunter explained in a letter-to-the-editor in the February 14, 1885 Humboldt Standard, the 21 Chinese men who remained in the jail at the time of the original expulsion were: one detained as a witness, one who “had been imprisoned for several days for some petty offense and he still remains there as his term has not expired,” four “awaiting trial for carrying concealed weapons, the violation of a city ordinance,” five who had been arrested in connection with a previous shooting incident on January 31, and ten arrested on the night Kendall died. DA Hunter wrote,

… soon after Mr. Kendall was shot, some of the police officers entered the Chinese store, from which the shots were fired, and took into custody all the Chinamen in the building, against six of them no charges were preferred. They just happened to be in the house at the time the shooting occurred outside. Not the officers nor anyone else had any proof of their being implicated. Not even the Chinaman who claimed to be an eyewitness to the shooting … was disposed to accuse them of crime. Of course they were set at liberty. The remaining four were charged with murder, and they are now in jail and their preliminary examination will be held as soon as the attendance of witnesses can be procured.

Hunter added that the 16 men “would have been released earlier but for the fact that they were afraid, had no stopping place, and no opportunity to depart.”

The names of the four men charged with murder are given in the records as Ah Kow, Lim Gow, Sing Yek and Ah Chooey. It’s unclear whether this Ah Kow was the same man as the court interpreter who had testified in September 1884 about hiring Johnny Fox as a special Chinatown policeman. Sing Yek was the owner of the store outside which the shooting took place. This store was located about halfway up the block on the north side of 4th Street between E and F (in the area which is currently a fenced-off parking lot beside the old Bank of America building).

Preliminary hearings for the four men were held in late February, and their trials were scheduled for mid-April. An interpreter who traveled from San Francisco to assist with the hearings theorized to reporters that the cause of the “great disturbance” in Eureka’s Chinatown had been “the rejection of Ah Kow as a member of their Masonic fraternity.” (Humboldt Standard, March 2, 1885, p. 3.) The Chee Kung Tong fraternal organization, often referred to as the Chinese Masons, had a lodge in Eureka in early 1880s, as shown by multiple contemporary newspaper articles (for instance, Humboldt Times, Aug. 19, 1881, p. 3). Another theory, put forward by “a gentleman who is very prolific in explanations of the doings of the Chinese,” was that two factions of Chinese Eurekans had quarreled “about the present Franco-Chinese war–the sympathy of one side being for their country and of the other for the French” (Humboldt Standard, Feb. 14, 1885, p. 2). A third theory, stated by the defense in the April 1885 trials, was that the fatal shot had been fired by a man known as Fong Tong, who had avoided being arrested on the night of Kendall’s death. Court records preserved in the collection of the Humboldt County Historical Society show that Fong Tong was involved in legal difficulties with other Chinese community members in the days before the Kendall shooting (Justice’s Court of Eureka, Feb. 5, 1885, “Complaint filed on the oath of Gong (Nan) Foy alleging that the crime of battery had been committed” by “defendant Sin Loy alias Fong Tong”).

For the trials of Ah Kow and Lim Gow, 11 Chinese witnesses returned to Eureka from San Francisco: six for the prosecution and five for the defense (Humboldt Standard, Apr. 13, 1885 p. 3 and April 17, 1885, p3; Daily Times-Telephone, April 24, 1885, p. 3). The main white witness in the two trials was a man named Millard LaGrange, who had been the first to reach David Kendall’s side when he was shot. In Lim Gow’s trial, LaGrange testified that “Lim Gow came from the store of Sing Yek and commenced firing down the street. He stood immediately under a lamp that hung over Sing Yek’s door. LaGrange stood about 9 paces from him while he was shooting” (Humboldt Standard, April 16, 1885, p. 3). In Ah Kow’s trial, evidence “pointed to the fact that the third shot fired was the one that killed David Kendall” (Humboldt Standard, April 14, 1885, p. 2).

Both Ah Kow and Lim Gow were found not guilty. The reasons for their acquittals were not given in the newspaper coverage, but it seems likely that the juries felt incapable of determining which man had fired the fatal third shot. On the motion of District Attorney Hunter, the court then dismissed the remaining two cases against Sing Yek and Ah Chooey, “because of insufficiency of evidence to convict” (Humboldt Standard, April 17, 1885, p. 3).

On April 18, Ah Kow, Lim Gow, Sing Yek and Ah Chooey, along with the eleven Chinese witnesses, returned to San Francisco (Daily Times-Telephone, April 19, 1885, p. 3). A few days earlier, the Humboldt Standard gave a haunting glimpse of these men after Ah Kow’s trial: “The Chinese now confined in the County Jail are feeling jubilant at the acquittal of their comrade, Ah Kow. They were singing last night” (Humboldt Standard, April 16, 1885, p. 3).

Like the juries in 1885, we are unlikely to determine who fired the fatal shot: whether it was one of the four men charged with Kendall’s murder, or Fong Tong, or someone else entirely. It is clear, however, that there were multiple eyewitnesses and suspects. I believe the witnesses’ testimony supports the conclusion that David Kendall had the misfortune to be crossing the street when gunfire broke out between several shooters, instead of being the target of a hidden assassin. Rather than an “unsolved murder,” I would argue that David Kendall’s death was a case of accidental manslaughter.

When 56 of the expelled Chinese Eurekans brought suit in the 1886 case of “Wing Hing versus the City of Eureka,” their charge was that the City officials “had due knowledge of the assembling of the mob and of the riot aforesaid” and that “the said defendant failed and neglected to quell said riot or to disperse said mob, or to protect the property” of the plaintiffs (Wing Hing versus the City of Eureka, Cal Poly Humboldt Digital Commons). To me, this seems a fair evaluation of City and County officials’ actions during the expulsion.

They failed to fully quell the riot, disperse the mob, and protect Eureka’s Chinese residents – although they did succeed in averting a massacre. But evidence does not support the characterization of Mayor Walsh, Sheriff Brown and DA Hunter as conspirators, or Councilman Kendall as the victim of a plot. David Kendall lost his life not to an assassin’s bullet, but to simple bad luck.

###

Dr. Alex Service is curator of the Fortuna Depot Museum.

You like history? Consider a subscription to the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE