An

unsolved murder in Eureka’s Old Town on February 6, 1885, was the

pretext to rid Humboldt of all Chinese residents. But were the

assumptions about who likely pulled the trigger incorrect?

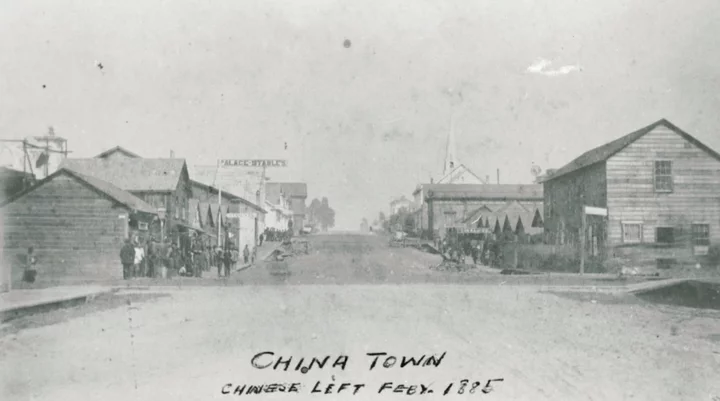

As Eureka celebrates its 4th annual Chinatown Festival today – 4-9 p.m. in Old Town — the truth of Eureka’s Chinatown expulsion is gaining importance.

The murder of Eureka City Council Member David Kendall

A series of seven to 12 shots pelted the crowd at 4th and E Streets in Eureka Chinatown at 6:05 p.m., Local Mean Time, on Friday, February 6, while daylight visibility was still good. But no eyewitnesses of the shooter were identified, despite many bystanders, both Chinese and white folks.

The bullets wounded several Chinese, hit a boy in the foot, killed one Chinese man and left Eureka Council Member David Kendall dead in the midst of celebrating “Little New Year” festival, also known as the Kitchen God Festival, which occurs one week before the main Chinese New Year Festival.

One week before, a similar series of shots pelted several Chinese folks at the same location, killing one and wounding several others, also in broad daylight in a crowded place, with no reported eye witness of the shooter.

“The ceremony to the kitchen god would have fallen on February 7, 1885, which would have corresponded to February 6th on the west coast of the US,” said Andrea S. Goldman, Associate Professor at the UCLA Department of History and Interim Director of the Asia Pacific Center, in an interview.

Zhang Meng, Assistant Professor at UCLA Department of History, agreed, and added that it is likely that there were publicly visible activities at the Eureka Kitchen God Festival February 6th, 1885.

Eureka Chinatown Festival interrupted for 138 years

Modern accounts of the expulsion have no mention of the fact this expulsion occurred during the Chinese Spring Festival season. Before diving into the unsolved murder and expulsion, let’s consider the Chinatown festival that was lost for 138 years before being brought back for the fourth year this weekend.

Before the expulsion, the annual Chinese New Years Festivals captivated many people in the white community who enjoyed them, but brought complaints from others.

February 14, 1877, the West Coast Signal reported on the Chinese New Year that “The fire-cracker demonstrations yesterday were worthy of mention.”

After the next year’s celebrations the local news reported, “The City Attorney has been instructed by the Common Council to draw up an ordinance, preventing the burning of firecrackers within the city limits, except on our National holiday.”

But the law didn’t succeed.

February 5, 1881, local news reported “The Chinese celebrated their new year yesterday, discharging firecrackers with a lavish hand. The boys about town took a conspicuous part as usual.”

The “Committee of 15” was formed to expel Eureka Chinatown

As dusk set in on Chinese “Little New Year” in 1885, the white town leaders conspired in Centennial Hall, a half a block away from Chinatown, to expel hundreds of Chinese from Eureka.

They quickly nominated 15 prominent community leaders to supervise the white mob in carrying out the expulsion.

The Committee of 15 was inaugurated and supported by Mayor Walsh, presiding over the meeting, Sheriff T. M. Brown, and District Attorney Geo. Hunter.

The Committee of 15 members included the following, as published by the Humboldt Times February 7, 1885:

- H.H. Buhne, Jr, son of Captain Hans Heinrich Buhne, one of the richest men in California, who owned a local general store, and was in the process of constructing a mansion and commercial building a few blocks away.

- Frank McGowan, lawyer and active anti-Chinese politician who went on to become a state senator and key member of the Asiatic Exclusion League.

- W. J. Sweasey, populist politician, born in UK, appointed secretary of the Committee of 15.

- C.G.Taylor, general store owner who went on to be a director of First National Bank.

- E.B. Murphy, Eureka City Council Member and owner of Western Hotel.

Howard Allison Libbey, “Prominent member of Lincoln Lodge, [Knights of Pythias], and No Surrender Lodge of Orangeman” according to his obituary that ran in the Humboldt Times on 23 September 1896. At Eureka’s Loyal Orange Lodge (L.O.L.) he served as “Worshipful Master” as reported in Humboldt Times 27 September 1883. Loyal Orange Lodges are a Irish-British Unionist and fraternal organization that uses similar practices to the KKK, but predates the KKK by a few hundred years, and with a structure resembling the Masons.

White citizen council and mob violence

One report documents how one of 20 Chinese arrested that night were detained by police: “The officers, after considerable difficulty, in which the Chinaman was pretty badly used by the crowd, succeeded in getting him to the lock-up.”

This method of orderly expulsion was quickly duplicated in other cities in Humboldt, including expelling Arcata’s Chinatown, and across the Western States. It was called the Eureka Method. The innovation came during the rise of violent white mobs in the wake of the civil war.

But while the South slid into the Jim Crow era during the rise of the first Ku Klux Klan that resisted Republican efforts to uproot the institutions of slavery, in the West the Republicans were aligned with Democratic efforts to create apartheid to deny equal rights to the Chinese. (For further detail on this disturbing history, see Kevin Waite’s article in The Nation: “The Forgotten History of the Western Klan: Whereas southern Klansmen assaulted Black Americans and their white allies, California vigilantes targeted Chinese immigrants.”)

Many of the Committee of 15 were Republicans. Several went on to become judges, bankers, and successful businessmen. They oversaw the crimes of the mob carrying out unlawful eviction, harassment and death threats.

A hangman’s noose was erected in the street to threaten the Chinese with murder if they didn’t board the first boat headed to San Francisco.

The Humboldt Times, in an article entitled “The Chinese Riot,” wrote “It was resolved that the Chinese be kept in the warehouses at the wharves and … that no Chinese escape and that all leave on the steamers in the morning.”

While technically a criminal conspiracy for unlawful detention and abduction, this vigilante justice had the blessing of the Eureka mayor, district attorney and sheriff in a blatant abuse of power.

Just before the expulsion there had been an editorial in the Times-Telephone with the caption “Wipe Out the Plague-Spots,” and the second day after the expulsion, a news headline read, “The Plague-Spots Wiped Out,” applauding the work of the Committee of 15.

An Unsolved Murder

The next day after Kendall was murdered another meeting was called. As Keith Easthouse reported in the North Coast Journal from an interview with author Jean Pfaelzer: “The sheriff, Tom Brown, stood up and told the crowd, in Pfaelzer’s words, that ‘I’ve arrested a bunch of men [20 by some reports] but I can’t tell you who shot David Kendall.’”

Chris Chu, Programming Coordinator of Humboldt Asian and Pacific Islanders (HAPI) in Solidary’s Eureka Chinatown Project told me, in an interview: “It is unsolved. Yes…There isn’t any hard evidence I can point to that says it was specific members of the community…I don’t think we have any of that information because it was pretty much whipped up into a frenzy pretty quick.”

The Chinese leaders at the time told the press they did not know who the shooter was, as the press reported on the second day after Kendall died: “So far as the tragedy of Friday night was concerned, both parties disclaimed any participation in it or any knowledge as to who the chief actor in that tragedy was.”

As the press reported at the time: “The audience was tremendously excited and if any direct clue to the culprits had been known they would have inevitably swung them to the nearest lamp-post. The utter impossibility of identifying the guilty parties proved however an unsurmountable impediment to their punishment.”

But the newspapers immediately and unanimously claimed, without hard evidence, that the shooting was the result of Chinese gang fights, and that assertion has remained largely unexamined ever since.

Chu said: “We have almost nothing from the Chinese perspective themselves, unfortunately, which makes it even harder to find the real facts of the story,”

But the historical archive does have signs that the Chinese were eager to be found innocent. An article in the Weekly Times Telephone on February 7, 1885, reported: “We were besieged most of yesterday afternoon by representatives from each faction, both anxious to ‘put em in paper’ their stories concerning the affray.”

“There is a very bitter feeling existing among the Chinamen,” the paper reported.

When the expelled Chinese arrived in San Francisco they hired a lawyer and filed suit against Eureka in Wing Hing v. City of Eureka, 1886, which ultimately failed when their attorney failed to meet filing deadlines. But the lawsuit contains dozens of names of expelled Eureka Chinatown residents, the amount of estimated damages, and the story that the local newspapers refused to tell.

The lawsuit lists the names of those expelled. Each claim asserts they were residing with their family, and doing business in Eureka with “large and valuable quantities of merchandise, clothing, provisions, furniture, fixtures, personal effects and money, belonging to him.”

Each claimant alleges “said rioters, acting together and without authority of law, riotously broke into the premises of [name of injured Chinese plaintiff] and carried away therefrom and totally destroyed his goods, merchandise, furniture, fixtures, clothing, personal effects, money and provisions, and drove him and his family from their dwelling and from said city, and caused them to be removed beyond the corporate limits thereof. The said defendant had due notice of the assembling of the mob and of the riot aforesaid, but the said defendant failed and neglected to quell said riot or to disperse said mob, or to protect the property of [name of plaintiff].”

Eureka’s response was that these businesses never existed and none of the businesses’ goods existed. They claim there never was a white mob and “denies that there was then, or at any other time, any riot at all in said city.”

What the lawsuit does not deny is driving them, or their family, from their homes and removing them beyond the city limits.

No reported witnesses of shooter on the crowded downtown street during daylight

There are no known reports of witnesses seeing a gunman, or a suspect fleeing the scene, even though as many as 20 Chinese were arrested and questioned by Sheriff Brown.

The shooting took place almost exactly at civil dusk, which is good visibility, when the sun is 6 degrees below the horizon, 25 to 30 minutes after sunset. That evening the sun set at 5:38 p.m. Local Mean Time, used by the Humboldt Times for local events until the early 1890s – 8 minutes ahead of Pacific Standard Time.

The shooter may have been a clandestine assassin, considering there were no known eyewitnesses of the shooter during daylight hours in a crowded place, despite a mob frantically searching for the shooter immediately afterward.

Shooter may have been clandestined

The shooter was not seen despite firing into a crowd while it was still daylight.

One possible explanation for this is that the shooter had selected a clandestine location so that they would not be seen by the crowd they were firing at.

Common strategies of clandestine gunman at the time included taking an elevated position and selecting to fire at dusk, while still daylight, for reducing risk of detection by reducing visibility of smoke from the gunshot, and muzzle flash.

There were multiple locations in the vicinity where a shooter could have taken a shot undetected such as in an elevated position, such as on a second floor, a roof, or a church tower. There were certainly plenty of elevated positions in the area that a gunman could have used within the 300 yard average limit for rifles of that era, including the Congregational Church bell tower, which was in full view of the reported victims on February 6, as well as the victims of a similar unsolved murder a week before that left one Chinese person dead and a few others injured.

Also, the number of shots, 7-12, is consistent with the number of shots in a standard rifle of that era.

Other pieces of circumstantial evidence don’t prove the shooter was clandestined, but would be made more likely if the shooter was. For example, the likelihood of hitting a child in the foot, as happened here, is greater if the shooter had chosen an elevated position.

There is precedent: The Los Angeles Chinatown Massacre in 1871, when 19 Chinese were murdered by unreported gunmen, some on rooftops firing down into crowds. There many white community leaders were involved in the brutal attacks on Chinese in broad daylight, but the prosecution struggled to get any eyewitness accounts to testify on the record. Just like Eureka, the media claimed the violence started with rival Chinese gangs shooting at each other.

Certainly the historical record is filled with many people calling to get rid of Eureka Chinatown. Chinatown massacres had already swept across the West in the previous years. The year 1885 was the second mass expulsion of Chinese from the area. The first was in the early gold rush days when an estimated one or two thousand Chinese were run off their successful gold mines near Grizzly Creek in the Trinity National Forest.

Politicians, ‘Committee of 15,’ and fraternal societies had been plotting expulsion and were members of groups with a violent racist past

The months and weeks ahead of the expulsion the newspapers were filled with people calling to get rid of Chinatown.

Chu, the from Eureka Chinatown Project said economic factors pressurized the white male workforce. Also, he said, “Humboldt had a lot of fraternities – male social and labor organizations that were tied to a lot of violence going back 25 years before the expulsion. The Wiyot Massacre was in many ways organized and carried out by these fraternity organizations.”

The ad hoc secretary for the meeting that formed the Committee of 15, W. J. Sweasey, was a populist politician, a former Republican born in Britain, and an owner of one of the steamers that transported the expelled Chinese to San Francisco.

Over five years before, Captain Sweasey was the first chairman, and elected the first president, of the Tax Payer’s Party, which issued a list of resolutions including that ‘All legal means should be used to halt the immigration of the Chinese “and other inferior races who cannot amalgamate with us.’”

Many researches have addressed the prevalence of fraternal societies and racist calls to expel the Chinese in the lead up to the expulsion, but significance of Committee of 15 member Howard Libbey’s prominence in the local Orangemen movement has received little, if any, consideration.

‘Prominent’ Orangeman was on the Committee of 15

Committee of 15 member Howard Allison Libbey was the head, “Worshipful Master”, of the Eureka Loyal Orange Lodge (LOL), located on Forth and G Streets, one block from Chinatown, as described in the Humboldt Times on September 17, 1883.

Orangemen, as they are called, are an Irish-British Unionist and fraternal organization that use similar practices to the KKK, but predate the KKK by a few hundred years, and with a structure resembling the Masons.

They were active in the US at the time of the Eureka Chinatown expulsion.

In 1871 they created one of the deadliest riots in New York City history. As the New York Irish History Roundtable reported in their sixth volume, the “Orangemen,” who are British and Irish Protestants, attacked Catholics in New York killing almost 80 people. The year before on their national day of rallying, July 12th, their riots killed eight in New York City.

The fact Orangemen were both heavily involved with the violence sweeping the country and represented in Eureka’s Chinese expulsion by a prominent local member of Orangemen on the Committee of 15 may have more significance than previous researches have explored.

Libbey’s obituary from the Humboldt Times (Sept 23, 1896) said: “Deceased was a prominent member of Lincoln Lodge, K of P, and No Surrender Lodge of Orangemen, having been secretary of the latter lodge for several years.”

The involvement on the Committee of 15 of characters like Libbey, McGowan and Sweasey, combined with the full support of the local media and politicians, raises serious doubts on the trustworthiness of their assertion that Kendall was shot by a Chinese gangster when there is no reported eyewitness of the shooter.

####

Shawn Leon is a Humboldt County resident and a Cal Poly Humboldt graduate.

You like history? Consider a subscription to the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE