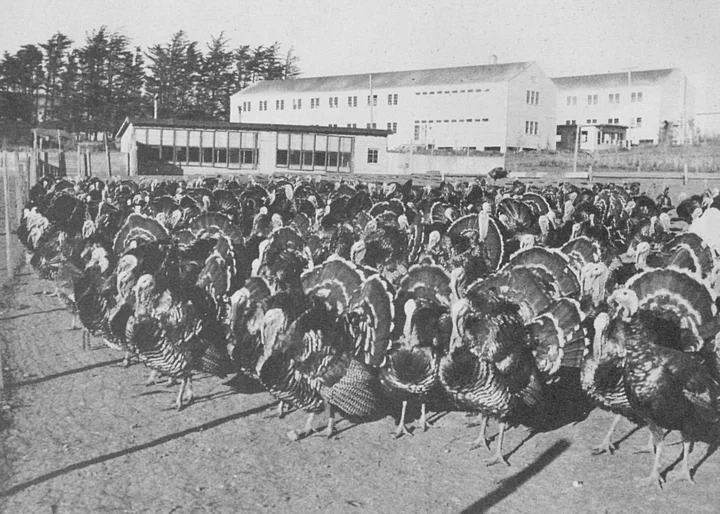

Turkeys at a farm near McKinleyville. Photos via the Humboldt Historian.

###

Author’s Note: A former poultryman and I were reminiscing about the past. We didn’t have answers to some questions. A search in the files of the county library and Humboldt State University historical records provided very limited information. The persons about whom we were interested had passed away, as had most other former poultrymen. Consequently, much information has been lost — permanently.

From that developed the idea of recording for the future something of the past poultry history of the county.

As there are no operating poultry in farms in the area, there are no opportunities for field trips by current FFA classes, or children interested in poultry. Soon teachers will not have had the pleasure of watching a hen mother her brood, will never see hens scratching in the hen house litter, will never hear the rooster crow at the crack of dawn! Just as the urban child says all milk comes from the cartons in the store, soon people will be saying eggs also come from the store, never realizing all that goes on behind the scene to have fresh eggs available for breakfast.

This writing may be of interest in future years and provide a picture of the poultry industry that once was there. When one tries to determine who had the first poultry in Humboldt County, or when the first poultry came into the county, or for that matter any information about the facts of poultry in the county, one has about as much success as the child on a fruitless search for the “hen’s tooth.”

###

It is a safe assumption to make that there was poultry of some kind — whether it be ducks, geese, chickens or turkeys — in the county shortly after the first settlers arrived. Early accounts of the settlers of the West often mentioned milch cows and chickens. There appeared to be a considerable amount of initiative on the part of local agriculturalists in the county. The County Assessor’s first report for the year 1854 indicated potato crops, 1,400 head for stock raising, 412 milch cows, grain crops. The year 1857 reported all kinds of fruit trees now in production, as well as grapes.

Dairy production took a turn toward an important business. In 1855 an enterprising merchant of Union (Arcata) advertised 3,000 pounds of “Premium Eel River Butter” and Humboldt cheese.

Ten years later, in 1865, it was reported again by the County Assessor’s Office that there were 8,100 chickens, 123 ducks, 175 geese and 303 turkeys in the county.

As the population increased, so did the demand for food products. A considerable amount of butter was exported to the mining and lumbering camps of other parts of the State. More importantly, the San Francisco market was putting a premium on Humboldt-produced butter. Success in this area could not help but stimulate the thinking about and the production of other crops in the area, such as eggs.

The development of the County area did not go unnoticed either locally or at the State level. In the early part of the 20th Century, Humboldt County Promotional and Development Committee was formed. It is quoted in both the 1915 and the 1916 issues of Humboldt County, California, published by Ward-Perkins-Gill Company as follows:

There are opportunities galore for commercial chicken raising in Humboldt County. It is so easy to produce abundant food for fowls on the rich hill and bench lands that only a reasonable knowledge of chicken raising and reacess. On such lands there is an abundance of small insects for the young chicken’s diet, and as the season advances myriads of grasshoppers make such locations a chicken paradise. Such lands are reasonably priced and a market for all out put is assured, for as yet Humboldt County imports large quantities of eggs and chickens, whereas it should be a large exporter of such products.

Although this report contains some questionable statements it nevertheless shows that there was aggressiveness on the part of the Committee to promote chicken and egg production. An earlier report (1903) of the County Assessor indicated that 2,372 dozen eggs had been valued at $5,795.

Humboldt County, Califomia, by Leigh-Irvine in the Historical Record Co. of Los Angeles 1913 records: “In forecasting the possibilities of poultry raising in the county, the southern part of the county should not be overlooked. Those experienced in this line of work are unanimously of the opinion that our climatic conditions are such that, coupled with our soil, make southern Humboldt the ideal spot for poultry business.”

Turkey Production

Turkey production started early in the county in the hill or mountain area of the southern part of the county and eastern edge of the Humboldt Bay.

Walter Eich, a former poultryman now resides on Humboldt Hill. He remembers while a student in the Lincoln Grammar School on Harris Street, Eureka, seeing aflockof about 600 turkeys being driven down Harris Street by two men on horseback with the help of one dog who put straying turkeys back into the mainflock,keeping the birds bunched together. These turkeys came from Kneeland. At that time it was reported there were a considerable number of turkeys raised in the Kneeland area.

In the early days of raising turkeys in the county, they were driven to a Humboldt Bay dock and shipped by boat to San Francisco where they were processed and sold on the market.

Another accounting of turkey drives comes from the book From Buckskin to Teambells by Vera Snider Teague. This story relates to one of the incidents told to her by her brother, John Snider, an old-time teamster.

In the days of the pioneers, livestock, including geese and turkeys, were often driven to market. Since transportation presented a problem, as well as other factors, such as a lack of refrigeration, the animals or poultry must be delivered alive for transportation was slow and uncertain that the produce would spoil before reaching its destination unless delivered on foot.

In southern Humboldt County, however, I found another reason for large herds of turkeys on the move. Many of the ranchers found the costs of feeding these large herds prohibitive so annually would start their herds out in the early summer, keeping them on the move for shipment in the late autumn.

One day when I was on my way from Bridgeville to Blocksburg, I met a band of perhaps five hundred or more turkeys. There were three herders, a man, a woman and a boy in his early teens. These were on horseback, but some herders went on foot; they had two well-trained dogs. There was a supply wagon drawn by two horses with all the supplies for the trip, including fencing for temporary campsites for the turkeys.

I pulled out until they got their herd safely past. Most teamsters were in the habit of showing such courtesy.

Two men in the party usually went ahead to locate a camp, where they set up the necessary pen. Seldom did turkeys have to be fed, for by evening they usually had all they could eat. But, if they passed through sparse feeding grounds, then grain feeding was necessary for the herd to bed down contented for the night…

Ranchers welcomed the turkeys, and when grasshoppers were heavy, some ranchers offered pay to turkey herd owners to come their way to help get rid of the pests. For the service, besides pay, they would provide quarters and food for animals and human beings.

The herd I had made way for had started from Freshwater, a small community about seven miles out of Eureka. They had consumed grasshoppers across Kneeland Prairie, over all the open ranges and through the little valleys. One could hardly estimate the many miles traveled during a season, for the herd was driven from ranch to ranch and crisscrossed ranches where the best feed was available.

By late August or early September the herders would start their flock homeward and the same grateful ranchers would let them fatten while gleaning the fields after the grain had been harvested. On reaching their home ranch they would be crated and hauled to the dock at Eureka where they would be shipped on steamships alive to their destination, to market, for there was as yet no railroad to Eureka.

Those of us who might think otherwise, are surprised to find the turkey provides no great ‘driving problem.’ As far as I could determine, the turkeys were as easy to drive as other creatures.

The procedure took patience, understanding and skill. The dogs were well-trained for their tasks and should a turkey start to wander from the herd, the dog would seldom need to be told. He knew his job and was always alert. He would gently urge the turkey back to the others. The turkeys seldom tried to fly. This would happen only if they should become extremely excited. Experienced herders and dogs knew how to prevent this in most instances….

We found, though, that where crossing a river was necessary, the birds were encouraged to make their own crossing—by air! Turkeys driven from Hyampom were roosted at night in trees to protect them from predators.

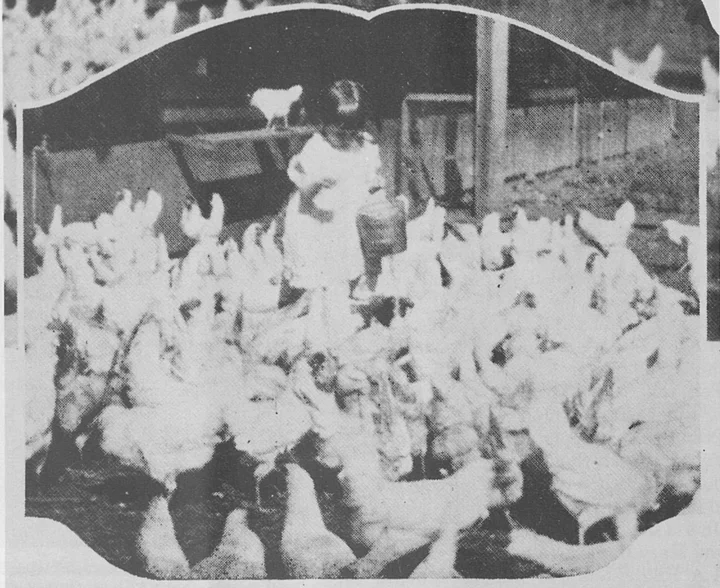

Raising poultry was often a family affair. This photo comes from the Society’s Greater Eureka Chamber of Commerce collection.

Egg Production

The production of eggs early in the life of the county was quite simple — farm flocks of relatively small number, turned loose to primarily forage for themselves. In the late afternoon or early evening a small amount of whole grains was fed to entice them into the chicken yard. At dusk they went to roost in the hen house and were locked in for safety from marauding predators which could raise hovoc with birds in just a short time.

One outlet for eggs was the local grocer. In the absence of money, the barter system of exchanging eggs for merchandise was followed in the most primitive time of the development of the county. With the development of shipping agricultural products via ocean going vessels, and a larger variety of merchandise in the mercantile stores, primitive bartering gave way to the purchase of eggs or credit to the account of those who gained the favorable status of credit customers. This system worked well until the merchant took in more eggs than he could sell. He would have to pay the freight to ship his surplus stock to Eureka or the San Francisco market. Obviously he would lower his price to the local farmer.

With the passage of time more and more people, probably listening to the glowing words of the Humboldt Promotional and Development Committee, or Mr. J.A. Robson who wrote in 1915, or who read in the 1916 Supplement to the Humboldt Times titled “Land, Dairy and Development,” became interested in poultry.

Some of the problems facing the poultry egg producers is described by Charles R. Farrer, president of the Poultry Producers of Northern California in his written work, “The History of the Poultry Producers of Northern California,” dated December 1948. Mr. CH. Farrer was the son of CF. Farrer of the Southern Humboldt area who was one of the early egg producers in the county. Mr. Farrer writes:

“During the ‘back yard flocks’ time, Humboldt growers could only produce according to the dictates of the local store owners who were in turn regulated by the buying power of the local population. Motivated by self interest, the small private store owner would take eggs only as payment for articles available in the store, including poultry feeds, while paying very little cash. The store’s policy was to insure the maximum of trade and so the owner would seldom take more eggs from one person than that person would take in goods.

People with chickens found that about 200 birds would furnish all the eggs that could be traded for desirable store items. Producers not only failed to receive cash, but they seldom got the equivalent value of the eggs under this one-sided barter system. People with this sideline job, caught between high priced feeds and good and low priced eggs, continued to raise chickens only because they hated to see the complete loss of their investment in birds and equipment.

The manner in which the eggs were marketed brought loss of demand and profits which hit both storekeeper and producer. Due to the barter nature of these transaction, the eggs were not graded or candled, nor packed in either crates or the now familiar one-dozen cartons. Eggs sold in paper bags from bulk heaps were often cracked, blood spotted, dirty, half-rotten and even fertile which, of course, did not enhance sales. Even the indiscriminate mixing of varying sizes of eggs, all for the same price, caused consumer reluctance.

A source of major loss to the storekeeper was the fact that seasonal fluctuations in egg production created an over-supply that had to be shipped from the county to find a market. As small batches of produce were too expensive to ship, it was customary for the store to collect several hundred dozen before shipping. As this collecting period lasted over possibly a month or so, many of the eggs were rotten and badly evaporated, leaving them completely unmarketable.

As time passed, the few old stores that had handled local eggs were forced to close because of poor business management, confronted by better organized competition. Often many of the ‘old timer’ run stores had most of their assets in their books as bad charge accounts.

The opening of local branches of chain stores was the first real market possibility, but they, like other business-like stores, preferred not to handle ungraded and unpacked eggs. Here was an outlet for production large enough for a man to raise poultry full-time provided the poultry raisers could work out a way to prepare their eggs for retail handling.

To meet these identified problems, several steps were needed. The first step was the production of clean eggs, addressed in part through management and housing. The second step was the cleaning of any eggs produced with even the minimal amount of foreign matter on the egg shell. The third step was the grading of eggs considering shell cleanliness, egg size/weight, and internal quality.

The Poultrymen

The economic bind put on everyone by the Great Depression of ‘29 was felt very strongly by poultrymen of the county. They looked for ways to increase their profits. A relatively new organization, the Poultry Producers of Northern California (P.P.N.C), worked hard to help conditions for its members.

Some poultrymen dropped membership in the cooperative and tried to go on their own. Only one was successful and he was Harry McClosky, the largest egg producer in the county.

McClosky was an elderly man, and the ravages of time claimed his life immediately thereafter. His son-in-law, David J. Henry, took a leave-of-absence from his school administrator position to return to Humboldt to assume management of the operation.

One might wonder if the claim of J.A. Robson, “One can with a reasonable amount of intelligence and very little knowledge of the business, make a very good profit on poultry raising” might or might not be true. Dave Henry was a man of considerable intelligence but minimal knowledge of the business when he took over. But he was a very practical man with an analytical mind.

He made an assessment of the business of producing and marketing eggs: become more labor efficient, reduce your operating costs, keep your houses full of chickens at all times regardless of the egg prices, produce the very best quality eggs on the market, look for new markets for your products, and provide outstanding service to your customers. This was his analysis of what it would take to become successful in the poultry business in the early ‘30s. These things he did, and became one of, if not the most, successful producers of the day.

One producer of eggs. Miller Farms of McKinleyville, had a good herd of high producing cows. Their chickens provided an additional source of income while members of the P.P.N.C. One side benefit of chickens for them was the fertilizer which helped maintain the productiveness of their fields enabling them to compete production-wise with dairies on the river bottom lands of Mad River. They were very strong in growing potatoes.

Miller Farms eventually bought an egg vending machine. They sold extra large and large eggs from the vending machine located in an open-faced shed at the edge of a drive- through lot on the ranch.

After the closing of the P.P.N.C, Miller Farms sold their eggs to Hillcrest Farms which had an extensive wholesale business in the area.

The farm has evolved into Miller Farms Nursery and Florist Shop on Central Avenue in McKinleyville.

Francis Randle

Francis Randle, an early poultryman in the county, had a poultry farm on the south slope of Bella Vista Hill facing the old Mad River covered bridge at Hannah’s Crossing. This ranch of 20 acres had only one acre cleared when originally purchased. At first he worked in the woods to earn a living but evenings and “off time” he cleared the land until eventually he had 17 acres cleared.

He built houses for 900 White Leghorn hens which produced eggs which he sold to the cookhouse and the grocery of the Samoa Lumber Mill at Samoa. In addition to the chickens, he also produced strawberries from 1,500 plants.

Randle had a close relationship with Luther Burbank, and from him he obtained some of Burbank’s newly developed green garden peas. He developed quite a good reputation for his berries and peas which were eagerly sought after. On May 1,1917, he sold this property to George Zender.

In 1917 Randle purchased 20 acres of land at 11 and Q streets in Arcata and a Mr. Gilardoni purchased the other 20 acres of George Zender’s farm.

On this property Zender built three, 165’-long buildings — two were double-deck houses and one was a single-deck house. He purchased 750 chicks at a time from Petaluma several times a year in order to keep his laying houses full. The chicks were hatchery-run. When five to seven days old, he could tell the roosters from the pullets, and if the feed prices were such that he could profitably raise the rooster chicks, he did so and sold them to Angelina Inn and other surrounding customers. If feed prices were high, the roosters were disposed of. He added A. Brizard Co., and Seely and Titlow to his customers for eggs.

A Mrs. Dunlap, who lived on 11th Street in Arcata, cleaned and candled eggs for Francis Randle at both the Mad River Ranch and the Arcata Ranch.

His grandson Rodney Thompson used to get a big thrill of riding with his grandfather in the horse-drawn buggy to Samoa to deliver the eggs and poultry, and then on the return trip to bring home a load of wood.

Randle died in 1934 and the chicken ranch was sold to the next door neighbor, Sebo Gilardoni, to expand his dairy farm.

More Than Producing Eggs

The work of producing eggs was not all done on the farm; some work was done in the P.P.N.C. egg rooms. The following is taken from a letter sent by Mrs. E. Lorene (Minnie) Allen, a 78-year-old widow now residing in Eureka, who worked there as a child.

I was only a worker there for two years or more. During the Depression my parents had a long divorce. There was no work and my father didn’t pay the $10 for each child per month for alimony. So I quit school at age 15, in the 10th grade, and I tried work of any kind. Of course, I lied about my age as we needed the work. I was hired at the Poultry Producers as an 18-year-old.

I was put on the washing machine with an older lady, Flonnie Cheetham (she died two years ago). My job was to scrape the worst manure off the eggs and put them in a long trough with a spiral metal rod that moved the eggs over brushes to Mrs. Cheetham who would receive them and place them into divided wooden boxes in layers of 86 dozen. Then Jettie Hill, in our egg department, would load them on a hand truck and take them to the next room to be candled by at least a dozen girls. Elsie McCartney was in charge and she would go over them once again before being placed on the high porch where trucks waited to deliver them. I think, if I recall right, she also placed the eggs in cartons.

In time I was advanced to a candler. We would work in a dark room and would whirl two eggs in each hand to the light globe and decide whether “blood spots,” which appeared very red, were present. These were put into boxes for fertilizer, etc. Our best quality eggs were called “blues,” which were large, white-shelled eggs. These were sent East as in that part of the country they only ate eggs with pale yolks. If the eggs weighed less and were as described above, they were called “greens.” All the others, due to any change in colors, were put into several other grades.

This company, at the time I worked there, was headed by Mr. Bob Moore. He was a serious man and, as my first boss, I was always afraid he’d fire me and I desperately needed the $54 per month as my mother had to have the $50 and I had $4 for car fare. But trying to save some money for Woolworth’s jewelry, I often walked the 2 miles home on A Street. We lived across from Mrs. Anderson, the truant officer. She was a tough lady and I could never use the front door as she would catch me, so I used the alley. I feared her.

A Mrs. Frances Roth was the office manager along with two or three other girls. Mrs. Roth and I became good friends and now and then I was invited to dinner, which I recall was a delight as kids were always hungry in that dreadful Depression of several years.

Fond memories of the girls who worked there are clear in my mind. Most are dead now: Rose Wager, Ollie Harris, Flonnie and Elsie and Helen Nash.

Later I became an usher at the State Theatre.”

###

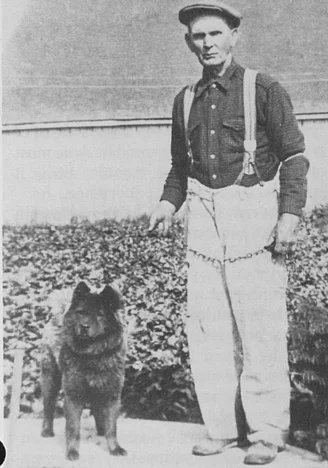

Elwain Dreyer was the former owner and manager of Hillcrest Poultry Farm.

The story above was originally printed in the May-June 1992 and July-August 1992 issues of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE