Above: Humboldt Times newsroom, 1954. Seated at desk are managing editor Elmer “Hodge” Hodgkinson at left, and Andrew Genzoli, county editor and noted local historian. In the background, from left, are Q. L. Wilson, in charge of the Times’ Arcata news bureau; Walter Johnston, general news reporter; and the author, then a staff writer. Photos via the Humboldt Historian.

Before I ever got to Eureka I started out in journalism in a mill town — Sanford — in the state of Maine. My first editor was Norman “Red” McCann. When he hired me he said, “Let me tell you, the press is the last outpost in a republic. Once the bastards get control of the government, once they get the courts, there’s nothing left but the press. Believe me, boy, we’re democracy’s last line of defense. Are you ready to roll up your sleeves and go to work?”

Red paid the ultimate price for his idealism. When a new group bought the paper, they wanted him to kill a story that was embarrassing to a prominent family. He couldn’t oblige. For twenty years he had been honest with the public record, and for his fidelity to the First Amendment he was forced to retire.

As he descended the stairs on his last day. Red kept saying, “Time to haul in the flag. The last bastion of liberty has been breached.”

In disillusionment and looking to start afresh, I headed west and eventually wound up in Eureka.

The rough and tumble life of Eureka in those days was liberation for a soul tethered to Old Testament and Puritan principles. Eureka spelled freedom for an adventurous youth of twenty-four. With its whore houses, card rooms, gin mills, loggers, ranchers, vast forests and a waterfront teeming witb crabbers, trawlers and ocean-going freighters, Eureka seemed like a brave new world.

The Humboldt Times, where I worked, was a morning paper. Its sister publication, the Humboldt Standard, came out in the afternoon. Both were owned by the Eureka Newspapers, Inc., at 328 E Street, between Third and Fourth Streets, in a two-story building. Harriet’s, and all-night restaurant, was a few steps away. The Annex Bar was next door, a refuge for Times journalists after the paper was put to bed.

Almost everyone on the paper had an alibi for working there. Elmer L. Hodgkinson Jr., or Hodge, as we called him, had fled his native Oklahoma when a sheriff showed up at his father’s house with a warrant for Hodge’s arrest. He was wanted for child support. “Just a minute, I’ll see if he’s in,” said Hodge. He threw some an clothes into a suitcase and skipped out the back door.

Don O’Kane, the publisher, who came down from Portland, liked to say he hit Eureka with fifty cents in his pocket, but if he’d had another fifty cents he would have kept on going.

Jehanne Salinger, the society editor, came up from San Francisco to escape a rocky marriage. Jehanne’s son, Pierre Salinger, was a reporter with the San Francisco Chronicle. He was later the press secretary to President Kennedy and, for a time, President Johnson. And for a brief period Pierre was one of California’s U S. senators.

Only Andrew M. Genzoli had nothing to apologize for. A regional historian and prolific writer, he was a proud native of Ferndale. He gave of his vast learning liberally in his writings, and also in his advice to fledgling journalists like myself. Andy was the only one of us who was probably indispensable.

As a stringer for the AP, Hodge was always on the lookout for stories that the wire service might want to run. A local story that “made” the wires not only put Eureka on the map, it also put a few dollars in Hodge’s pocket.

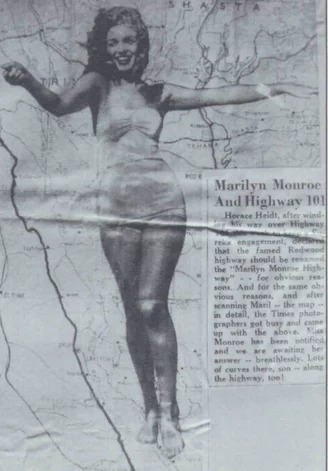

A good example would be when Horace Heidt, the bandleader, came to town. When Heidt disembarked from his bus in Eureka after an adventurous ride from the Bay Area, the shaken musician suggested that tortuous 101 be renamed for Marilyn Monroe.

Hodge chuckled as he read my copy. Then he waved me over to his desk. An idea was coming to boil.

The next morning the Horace Heidt suggestion was the peg for a front page story accompanied by a picture of the curvaceous actress superimposed on a map of the Redwood Highway. Readers were told that we’d forwarded the idea to Miss Monroe and that we awaited her response — breathlessly.

She replied in a telegram a day or two later. “1 appreciate the humor in your story,” she said, “but I couldn’t go along with the Horace Heidt suggestion even in jest.”

Marilyn Monroe may have declined the honor but Hodge was not dismayed. The AP ran the Monroe story. It netted Hodge $5 or $10.

At this time — the mid-1950s — agents of the communist conspiracy were assumed to be everywhere: in federal, state and local governments; in towns large and small; in the house next door. The Reds were in the schools, contaminating the water, and in the churches. And the liberals were the usual suspects. In this fearful climate, another idea was percolating in Hodge’s head. I sensed it the moment he chuckled softly to himself and lit a cigarette.

“Boy!” he called out to me. “How many highway fatalities would you say we have every year? One a week, maybe more? High time to do something about highway safety.”

And with a few taps on the keyboard Hodge brought into being an organization of quasi-vigilantes called Drivers Alert. The headline screamed:

ALL-OUT WAR DECLARED

ON DRUNKEN DRIVERS!

DRIVERS ALERT TO BE EYES

OF THE LAW

The article called upon motorists to report incidents of reckless driving as a backup to law enforcement. Hodge had struck a nerve. In a week we collected hundreds of dollars in membership fees. We took in more money in the following weeks.

“If the response keeps up this way,” said Hodge, “we’ll be in the running for a Pulitzer.”

But as Ernie Snowberger, our staff skeptic, observed, Hodge and I had turned a lot of nuts loose and now how were we going to get the genie back in the bottle?

Drivers Alert members were taking to the highways and streets and running after drivers — in some instances to settle scores with neighbors and people they didn’t like. The police, no fans of Hodge’s brainchild, were not amused. Worse, crusaders tramped up to the newsroom besieging Hodge and me with notions on how to bring wayward drivers to justice. We were spooked. Hodge and I were ink-stained wretches, not organizers. After a period of indecision, we recruited a committee of top people to take control of the movement.

But before we took the step Hodge, Ernie, Al Tostado, and I made good on all our IOUs to Drivers Alert. Frequently broke, especially before payday, we dipped into the sboebox where the Drivers Alert membership funds were kept. Our laissez-faire behavior was probably felonious (though we left IOUs behind) but consider: When you’ve worked till midnight and you’re as dry as a bone, and the bars close in two hours and you’re young and your heart’s on fire, you’ve got to make allowances.

Such was the philosophy Al and I espoused. And Ernie, too, though he was our conscience.

###

Although full-page Sunday features were popular with readers, the pieces were done on our own time. Hodge couldn’t spare us during the six-day week. Neither would O’Kane pay for overtime. As Hodge put it, the publisher is guaranteeing us forty-eight hours of gainful employment every week.

“Sunday’s my only day off,” I protested.

Hodge shook his head. “I thought you were looking for experience, boy, making a name for yourself.”

Hodge’s mother was half Arapaho, and be took a fierce pride in that part of his ancestry. Not surprisingly he took a keen interest in the Indian tribes in our circulation area. Yurok basket-weavers, sweat houses, Hoopa medicine men, ceremonial feasts and deerskin dances, and Klamath fishers and waterfowl hunters were Hodge-assigned features broadening my education as a young journalist.

In fact, Hodge was curious about everything. So, at his bidding, I explored the Del Loma caves in Trinity County, said to be a bandit hideout in frontier days; microscopic life on the shores of Humboldt Bay; a pygmy forest of pine and cypress in Mendocino County; an ancient lighthouse in a boiling sea off Crescent City; the terrible beauty of a logging operation in a redwood forest; the life of a commercial fisherman; the derring-do of steeplejacks; the tactics of a sheepherding rabbit.

I passed some five wonderful years under Hodge’s tutelage at the Humboldt Times. But without knowing it I was looking for a way out. The midnight chases in police cars had palled; the rowdiness at council meetings induced torpor.

My humor did not improve with Hodge pressing me every night for a fresh highway fatality or stickup, even a second-rate burglary.

“This paper’s dying on La-VINE,” Hodge said whenever I returned from my rounds empty-handed.

I began taking small parts in plays produced by the Union Town Players in Arcata. At dinnertime I’d scamper down the flight of stairs from the newsroom. My wife Donna would be waiting in the car outside with the motor running and a hot dinner. We’d race for the theatre as I wolfed down supper. As soon as the directors, Don Karshner or Bob Titlow, ran me through my few lines and dismissed me, we’d tear back to Eureka. Donna would get off at our H Street apartment and I’d fly off to the City Council or School Board or Sheriff’s Office — wherever the news beckoned.

A play I remember well was “Arsenic and Old Lace.” Gayle Karshner starred as one of the crazy old aunts. Jimmy Householder, my friend and a popular math professor at Humboldt State, played the mad Dr. Einstein. I was the genial, slow-witted Irish cop. In a production of Chekhov’s “Marriage Proposal,” I played the neurotic suitor, Cliff Peterson. A friend who ran a haberdashery in Eureka stole the show as the irate father.

###

The author and Tricky Dick.

At about this time something new was in the wind — television. Like most newspaper people, I did not acknowledge TV as a serious medium for news. But the people running KVIQ were looking for a journalist to do the local news. The salary was $150 a week, $25 more than I was making at the newspaper. I would also be given a Volkswagen van for my personal use as well as for business. Hodge raised no objection to my leaving. If the move distressed him, he gave no sign of it.

In the fall of that year — 1962 — Richard Nixon was making his comeback. He’d been defeated two years before by John Kennedy in a contest for the presidency. Now he was running for governor of his native California. His itinerary called for a stop in Eureka.

Shadowing Nixon at this time was a story involving his younger brother, Donald. Questions were raised about a $205,000 loan that Howard Hughes, the reclusive billionaire, had made to Donald Nixon when Richard Nixon was Eisenhower’s vice president. For collateral the younger Nixon had put up a piece of property worth only $13,000. The press was asking why Hughes had been so generous to the vice president’s brother? Was there a quid pro quo? Was Richard Nixon linked to the deal? Up to now he had not been faced with questions about the loan on television.

KVIQ was an NBC affiliate. I queried the network: would it be interested in a spot with Nixon? The reply came quickly back, yes!

When I stepped into the room at the Eureka Inn for the Nixon interview, my cameraman, Buster DeBrunner, was grinning. The crew shooting commercials for the former vice president was offering us the use of their equipment. This was a big deal. We were a small station and had to make do with an antediluvian Auricon movie camera. It could shoot for only two and a half minutes before it was necessary to reload. Thus spontaneity, the essence of a television interview, would be lost. The Nixon crew’s camera was state-of-the-art, able to shoot non-stop for twelve and a half minutes. So now I was beaming, too.

Nixon stepped into the room. He moved lightly, efficiently, reminding me of a traveling actor who played many parts. 1 fired my questions about the Hughes loan. He kissed me off with finesse. Oh, yes, he’d heard all those rumors, but there wasn’t a scintilla of truth in any of it. And he went on, denigrating the allegations.

Nonetheless, the network wanted a minute of the interview. The substance of TV is not merely what someone says but the facial and body “language” with which it’s said. A “no comment” can sometimes convey high drama.

Buster and I gathered up our gear and the precious film, hugged the ad men for their benevolence, and tore off for the station.

I leaped to my desk while Buster dashed into the dark room. “Tell NBC we’ve got Nixon responding to the Hughes story!” I cried out to the receptionist and began typing. As I pounded out the script for narration I could hear Buster swearing. I ignored him but his voice grew louder.

“It’s ruined,” Buster said.

“What’s ruined?”

“The sound. It’s gone — erased, wiped out!”

Of course we lost our moment of glory on the Huntley-Brinkley Report. NBC wasn’t interested in a soundless interview.

We sent the film to a lab in San Francisco for answers. The analysis pointed to a number of possibilities — the film might have been defective, something might have gone wrong in the processor, and so on.

But in our hearts we believed Tricky Dick had struck again and taken us for the country bumpkins that we were!

###

Coca-Cola sponsored our local news program. Before we switched to the network in New York for the NBC Nightly News, the deal called for me to hold up a Coke, invite viewers to join me in “the pause that refreshes,” put the bottle to my lips and take a swig.

My hand shook so much, I could only raise the bottle a few inches the from the news desk.

Buster made obscene gestures in an effort to loosen me up. Sam Horel, the station manager, planted himself next to the camera. To this day I can hear him muttering, “Drink the Coke, schmuck.”

Night after night they tried in vain to get me to drink the Coke. Fortunately, the ratings were pretty good so I kept my job. But soon Sam was after me to produce a documentary. It was to be about a real estate development in the redwoods south of Eureka. The “documentary” he was touting was not a legitimate news story at all, but a thirty-minute commercial masquerading as one. I couldn’t do it. People would no longer trust me. I’d lose my credibility. Sam backed off but the handwriting was on the wall.

While all this was going on, NBC News was reminding reporters in the affiliated stations that the deadline for applying for an RCA/NBC Fellowship to the Graduate School of Journalism at Columbia University was at hand. I spent many days filling out forms, getting recommendations, writing an essay for admission and arranging for transfer of my undergraduate records from the University of Maine.

Months passed. I’d forgotten the whole business when I answered the phone in the pressroom in the Eureka City Hall. On the other end someone said, “Mel Lavine?” Then he introduced himself. It was an unfamiliar name. “This is Milton Brown.” And then, “NBC News New York. Con-grat-u-LATIONS!”

A year later — in the late spring of 1964 — I graduated with a master’s degree in journalism from Columbia. I offered my benefactors first refusal, and NBC hired me as a news writer. My goal was to land a job on the prestigious Today Show. It was a period when the media were rediscovering America’s grass roots. Just before I went in for the Today Show interview friends urged me to talk up my Eureka years. I took the advice. In the end the producer said, “I believe you’re just what this show needs.”

I worked with Frank McGee and Barbara Walters, hosts of the Today broadcast, and then with Jim Hartz and Barbara, and later with Tom Brokaw and Jane Pauley. They succeeded Barbara when she left NBC for ABC to become the first million-dollar-a-year journalist and a superstar. During these years I lectured around the country and worked up a talk on news-gathering entitled “The Media — Lap Dog or Watchdog?” But when I took questions people wanted to know what was Barbara Walters really like?

In 1978, after fifteen years at NBC, I accepted an offer from CBS to write and produce for a new program, Sunday Morning, hosted by Charles Kuralt. I was the original writer for Sunday Morning when the broadcast went on the air in January of 1979. The show was anchored for many years by Kuralt and since then by Charles Osgood. Sunday Morning is still going strong and will be thirty years old come next January During my many years at CBS I spent one required memorable year as a writer and producer on a documentary for Walter Cronkite.

###

While I was with Sunday Morning I got a phone call from the vice president of the Eureka branch of the Bank of America. It was about Drivers Alert, Hodge’s most successful brainchild. By now Hodge had been dead a few years. The publisher, Don O’Kane, had died some years earlier. The newspaper had changed hands, taken over by a British chain. Hodge had been elbowed aside, a new editor installed in his place. With little to do and shorn of authority, people told me that Hodge had started drinking again. He was sixty-seven when he died of kidney failure.

For many years I’d worried about people finding out that Hodge, Al, Ernie and I played fast and loose with Drivers Alert’s money, using it as if it were our personal bank. If word ever got out, people surely would condemn our behavior as criminal, a betrayal of the public trust — though we’d redeemed every last dime before turning the money over to a committee of responsible citizens.

“You called about the money?” I said. Like an animal frozen in the headlights, I thought I was a goner. No use playing games; cop a plea.

The banker was indeed calling about the money.

He’d sought in vain to bring the matter to the attention of people who’d served on the committee. Several were deceased, some too ill to see him, a few left no traces. Then he remembered me.

The funds, now totaling a few thousand dollars, I believe, had gone unclaimed for more than thirty years. Drivers Alert, long defunct, could no longer be carried on the books. The money had to be liquidated.

“What happens in cases like this?” I asked, greatly relieved.

“The money goes to charity. Do you have a favorite charity?”

“Yes,” I said, remembering how proudly Hodge spoke of the Indian blood he’d inherited from his mother’s side. “The Arapaho Indians.”

“Are you sure?”

I was sure, and sure it would have been okay with Hodge, too.

###

Looking back, I can say that because of Hodge — Elmer L. Hodgkinson, Jr. — Eureka was my university. Hodge may have been shy, often diffident, sometimes self-deprecating. But he was witty and imaginative. All he wanted from a reporter were stories, the more exciting the better. His outlook happily reminded me of what Ted Gumble of Civil Defense had said when I first hit town:

“Out here we don’t care where you’ve been. We only want to know where you’re going.”

###

The story above was originally printed in the Winter 2008 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE