UPDATE, 3:18 p.m.:

After this story was published, Undersheriff Justin Braud provided the Outpost with answers to the questions we submitted last month. Read more here.

###

Original post:

An automated license plate reader (ALPR) camera. | Image courtesy Flock Safety.

###

The Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office appears to be routinely violating its own policy and state law with its handling of information collected by automated license plate readers (ALPR). Data logs obtained by the Outpost show that the Sheriff’s Office is allowing outside law enforcement agencies to conduct hundreds of thousands of searches per month of its ALPR data, often without first obtaining legally required information such as the reason for the search and the identity of the officer conducting it.

While many of the searches list criminal codes or case numbers as the reason for accessing Humboldt County’s ALPR data, thousands of them include no justification at all, a violation of both California law and the Sheriff’s Office’s own policy. Tens of thousands of other searches were allowed despite listed reasons that contained only one- or two-digit numbers or generic terms such as “crime,” “case” or “investigation.”

Such vague justifications not only violate state law governing the handling of ALPR data, but civil liberties advocates say they fail to provide the level of accountability and transparency needed to justify the use of such surveillance technology.

The data logs reviewed by the Outpost also reveal that hundreds of searches were conducted by state and local law enforcement agencies that referenced federal agencies, including Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE), to justify accessing the information. State law expressly prohibits the sharing of such data with federal agencies, though investigations have found that this law is routinely broken.

The Outpost sent a long list of questions about these practices to the Sheriff’s Office nearly a month ago. On Sept. 30, Lt. Conan Moore, who oversees the office’s ALPR program, said via email that he was working on answering “all the questions” and would respond as soon as possible. He assured us several times since then that he was working on responses. As recently as Oct. 14, Lt. Moore said he’d try to answer the questions by the end of the day, but to date he has yet to do so. An email sent to Humboldt County Sheriff William Honsal Wednesday morning has also not received a response.

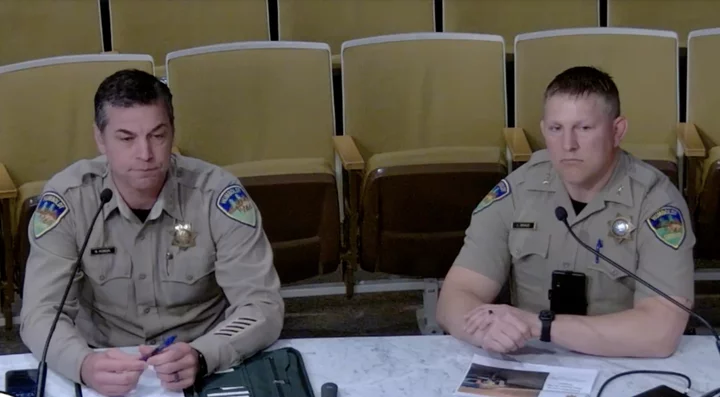

Humboldt County Sheriff William Honsal and Undersheriff Justin Braud report on the county’s ALPR system at a Board of Supervisors meeting in April 2024. | Screenshot.

###

Last year, the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office formally launched its automated license plate reader program by announcing and explaining it at a Board of Supervisors meeting. This technology, which has grown increasingly popular among law enforcement agencies despite privacy concerns on both the left and the right, employs high-resolution cameras to record and analyze the license plates of passing vehicles along with the make, model and color of each car and other identifying features, such as scratches and dents.

Advocates of the technology say it gives law enforcement a powerful tool to help locate criminals, stolen vehicles and missing people. Critics, meanwhile, argue that it enables a form of mass surveillance capable of tracking an individual’s movements close enough to reveal where they live, work and visit. Such technology is prone to misuse, these critics argue, particularly given the potential to target immigrant communities by sharing data with federal agencies such as ICE.

At the Board of Supervisors meeting on April 9, 2024, Sheriff Honsal and Undersheriff Justin Braud said their office would use its ALPR cameras — supplied by Atlanta-based police technology company Flock Safety — to enhance public safety while respecting the privacy rights of local residents.

However, the Outpost found that the office’s official ALPR policy contains numerous provisions that the agency is not complying with. Among those is a requirement that each request to access the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office’s ALPR data be submitted in writing, then reviewed and approved by the administrator (or an authorized designee) before being granted. [CORRECTION: The current policy does not require requests to be submitted in writing. See our more recent post for more info.]

We asked Lt. Moore whether that’s being done, but it hardly seems possible given the volume of searches the Sheriff’s Office is allowing. Data logs obtained through a California Public Records Act request show that, in one 30-day period, from early June through early July, the Sheriff’s Office allowed more than 781,000 searches of its ALPR data, granting access to 285 different state and local agencies. That amounts to more than a thousand searches per hour, 24 hours a day.

Mass Surveillance

Dave Maass, investigations director at the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), has spent more than a decade investigating the civil liberties implications of ALPR and its use by law enforcement.

“The thing to know about license plate readers is that they’re a mass surveillance technology, and by that I mean they collect information on everyone, regardless of whether you have any nexus to a crime at the time that it’s collected,” he said in a phone interview. “That means an officer can sit down at a computer and type in your license plate and then see everywhere you’ve been seen on camera.”

Data held by Flock is typically deleted after 30 days, but there are few limits to how often the information can be accessed, and there’s lax oversight of data sharing, according to Maass.

“Given the current political climate, there are a lot of concerns about how this might be weaponized against certain targeted or vulnerable communities,” he said. “That might be ICE using it to go after migrants; it might be malicious law enforcement agencies going after journalists; it could be trying to find people who are seeking abortions or trying to get their children gender-affirming care.”

Tracy Rosenberg, advocacy director for the nonprofit group Oakland Privacy, said such concerns have been exacerbated by recent political and legal developments, including a Supreme Court decision that cleared the way for ICE to use racial profiling as grounds for immigration stops.

“A lot of these hypothetical concerns become 100 percent real right away if you are, in fact, hunting people — and the federal government is, in fact, hunting people,” Rosenberg said. “This [ALPR technology] is a really good tool to find out where they are.”

Back in February, the Eureka City Council unanimously rejected a proposal from the city’s police department to install a network of ALPR cameras after many residents said they worry the information could be obtained by federal immigration officials and used to target undocumented community members.

A decade-old California law known as Senate Bill 34 bars state law enforcement agencies from sharing license plate reader data with out-of-state public agencies or federal entities. Likewise, the 2017 California Values Act restricts state and local law enforcement agencies from using their resources for federal immigration enforcement.

“But what we’re seeing is that individual police departments are, from time to time, basically breaking that safety net,” Rosenberg said.

A 2023 investigation from civil liberties groups found that 71 California law enforcement agencies had broken SB 34. Attorney General Rob Bonta subsequently issued an advisory providing specific guidance on how state and local agencies should follow the law. He reminded them not to share ALPR data with the feds and reiterated the requirement to document the reason for their inquiries every time they access the information, as noted in a recent CalMatters story.

Still, many agencies continue to violate the law. A recent investigation by tech journalism website 404 found that ICE was accessing Flock’s nationwide network of cameras by having local law enforcement agencies search the databases on its behalf, thereby “giving federal law enforcement side-door access to a tool that it currently does not have a formal contract for,” the story found.

A subsequent CalMatters investigation in June found that Southern California police had violated state law more than 100 times in a month by sharing ALPR data with federal agents. San Francisco and Oakland also appear to have repeatedly broken state law by sharing ALPR data with federal law enforcement agencies, including the FBI and ICE, according to a recent investigation by the SF Standard.

Earlier this month, Attorney General Bonta sued the City of El Cajon, accusing its police department of repeatedly violating SB 34 by sharing ALPR data with law enforcement agencies in more than two dozen states.

Despite such examples misuse, Governor Gavin Newsom this month vetoed a bill that would have strengthened regulations on ALPR use, saying it would have impeded criminal investigations.

Numerous law enforcement agencies alleged to be violating state law, including the El Cajon Police Department, the Oakland Police Department, the Menlo Park Police Department, the Sacramento Police Department and several SoCal agencies, have routinely been granted access to the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office’s ALPR data.

A law enforcement officer accesses ALPR data from her patrol vehicle. | Photo courtesy Flock Safety.

###

While there’s no indication from the logs we reviewed that the Sheriff’s Office is sharing its ALPR data directly with federal agencies, it appears to be allowing outside agencies to do so routinely.

The logs, which are maintained by Flock, document every time the data captured by our local sheriff’s offices cameras is accessed, whether by outside agencies or local officers and deputies. Each entry is supposed to identify the requesting officer and agency, the reason for the request, the timeframe being searched, the date and time of submission and the number of Flock networks included in the search, but, as detailed below, they often don’t.

But when reasons do get listed, they are often the names or acronyms of federal agencies. For example, we found a dozen entries listing HSI, which refers to ICE’s Homeland Security Investigations unit, according to Maass. Another 93 searches listed the FBI. More than 70 others listed USMS (the U.S. Marshals Service) and nine simply listed “fed.”

Insufficient Documentation

In the logs obtained by the Outpost, more than 2,200 searches left the “Reason” field blank. Tens of thousands of others entries listed reasons so vague (“investigation,” “suspect,” “case,” “law enforcement,” “criminal justice,” etc.) that they could apply to virtually any investigation. (Meanwhile, in the documents turned over to us, more than 400 entries in the “Reason” field had been partially or completely redacted. It’s not clear who made the redactions or why.)

Rosenberg said such entries violate both the spirit and the letter of SB 34.

“Although that state law is not, shall we say, super specific, it’s fairly clear that what they meant [by “Reason”] was an identifiable purpose that could be articulated and identified in the interests of basically any kind of audit or review,” she told the Outpost. “The primary problem with writing something like ‘criminal justice,’ which, as far as I know, is an academic field of study, [is that] it doesn’t tell you anything. … Nobody knows [what it means] except the individual who just put that entry into the journal. And if enough time goes by and they’ve done a number of these, they won’t even remember!”

Even the entries that list case numbers or codes likely don’t comply with state law, she said.

“It makes it very difficult for anyone who is auditing, reviewing [or] supervising unless there’s a standardized way for doing this,” she said. “Do these codes mean exactly the same thing at each department? … The penal code does, but some of these references don’t match up to the Penal Code. They’re just numbers and letters or somebody’s initials or whatever.”

Other entries in the logs turned over by the county don’t identify the officer who conducted the search of its data. Thousands list only a single letter in the “Name” field. At least three dozen searches conducted by the Northern California Regional Intelligence Center put the number 4 in the “Name” field. Seven searches by the Fullerton Police Department listed just a period.

Without the ability to trace who accessed this data and why, it’s impossible to know whether the searches were done for legitimate law enforcement purposes, Rosenberg said. Sometimes they’re not.

For example, a 29-year-old fitness influencer in Riverside County is suing the county sheriff’s department, alleging that after meeting one of its deputies at a festival in 2023, the officer used his law-enforcement access to stalk her, running database searches, tracking her movements and showing up at her house, making her feel unsafe.

In a similar case, the author of SB 34, former State Sen. Jerry Hill and his wife hired a private investigator to pull information from a Sacramento ALPR database regarding Hill’s spouse. The investigator obtained a photo of her car outside an area gym, the Los Angeles Times reported.

“My wife is an ordinary citizen, and the database was used to track her down,” he told the paper. “Anybody could abuse the power too easily, and that’s the genesis behind SB 34. It’s too easy for bad actors to help themselves to data.”

But even that state law is not preventing abuses, according to civil liberties groups including the ACLU.

Rosenberg said the growing ubiquity of ALPR technology only increases privacy concerns.

“When there were only 10 percent or 20 percent of police departments using Flock equipment, it was more anecdotal, right?” she said. “But now that we are at, like, 85 percent saturation and growing — and police departments that have these cameras are getting more and more and more of them — it’s becoming a much more invasive and comprehensive surveillance technology.”

Other Policy Violations

The only ALPR policy available on the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office’s website that the Outpost could located is this one, which is buried deep on page 498 of the office’s policies and procedures manual. It appears to be a boilerplate document based on a template employed by many other law enforcement agencies in the state, and it contains multiple provisions that the Sheriff’s Office does not appear to be following.

For example, it quotes a California Civil Code section that says all ALPR users must “develop a usage and privacy policy, which must be conspicuously posted on their website, and must contain provisions designed to “protect ALPR information from unauthorized access, destruction, use, modification, or disclosure.”

If the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office has developed such a policy, it is not posted conspicuously on its website. Attorney General Bonta reiterated in his 2023 guidance to law enforcement agencies:

Inclusion of such a policy in a manual, without noting on the main web page of their agency the existence of and/or link to such a policy, may not satisfy SB 34’s requirement that such policies be “posted conspicuously on that Internet Web site.”

Furthermore, both the Sheriff’s Office’s policy and state law say that the administrator of each agency’s ALPR system shall develop guidelines and procedures that include, among other things:

- the name and title of the person overseeing the ALPR program,

- training requirements for all authorized users, and

- a description of how the ALPR system will be monitored “to ensure the security of the information and compliance with applicable privacy laws.”

The Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office does not appear to have done so.

The policy also says ALPR system audits should be conducted on a monthly basis. We could find no evidence that the Sheriff’s Office is conducting such audits.

When Sheriff Honsal and Undersheriff Braud announced its ALPR program to the Board of Supervisors last year, Braud said, “This type of technology is going to do nothing but improve our ability to serve the constituents of this county, and also do it in a way that respects their privacy and their rights to not be infringed upon.”

Honsal told the board that his office would soon implement a “transparency portal” for its ALPR program so that the community could track how the technology is being used.

“The transparency portal that we’re going to have is going to provide that information to the public to say, ‘This is how we’ve utilized the technology, these are the successes of the technology,’ and hopefully we can see that grow, and that would be the ultimate goal,” Honsal said.

More than a year and a half later, no such portal has been made available to the public.

Among the questions we submitted to Lt. Moore was whether a transparency portal exists and why the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office appears to not be complying with several elements of state law and its own policy. We will update readers when and if anyone from the office responds.

CLICK TO MANAGE