Fish tagging on the Klamath. | Photo courtesy CalTrout.

###

PREVIOUSLY

- As of Today, the Klamath River is Flowing Free for the First Time in More Than a Century

- A Century Later, Salmon Again Spawning in Upper Klamath River After Dams Removed

- Indigenous Kids Are Kayaking the Entire Length of the Klamath River For the First Time Ever

###

A year after the Klamath River was returned to its free-flowing state by way of the world’s largest-ever dam removal project, scientists say nature has rebounded in astounding ways.

In an online press conference this afternoon, a group of scientists from regional tribes, environmental nonprofits and the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife reported observations and data from a year’s worth of fish monitoring, spawning habitat surveys, water quality testing and more.

The consensus was that things have gone better than anyone could have anticipated, particularly when it comes to fall-run Chinook salmon.

“What the fish have shown us is something extraordinary,” said Damon Goodman, Mount Shasta-Klamath regional director for California Trout. “The river seemed to come alive almost instantly after removal, and the fish returned in greater numbers than I expected, and maybe anyone expected.”

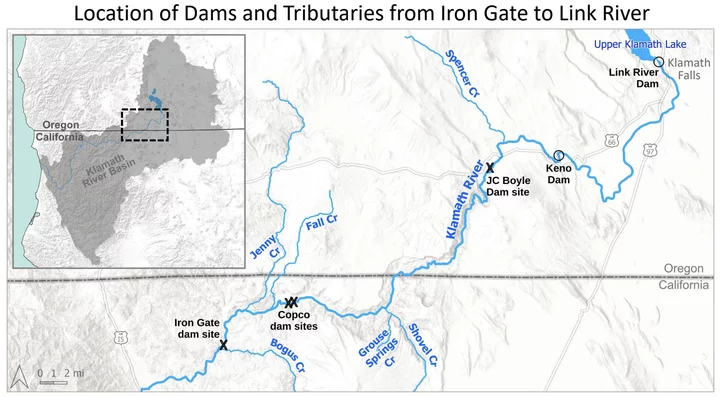

Scientists from a broad array of organizations have united under the common goal of learning how salmon, other anadromous fish and an entire ecosystem recover. The removal of four hydroelectric dams on the lower Klamath has allowed for the restoration of more than 400 miles of habitat.

Map of the Klamath River and tributaries showing the location of the four removed hydroelectric dams.

###

Yurok Tribal Fisheries Department Director Barry McCovey Jr. said the Klamath’s improved water quality, including a dramatic decline in suspended algae, has been a game changer for the tribal fishermen who have fed their people through gillnet fishing since time immemorial.

Fall-run Chinook are entering the river earlier than they used to and traveling further upriver than they’ve been in a century. The ones that returned to the Klamath in August were so robust and chubby “we call them footballs,” McCovey said.

In talking with tribal fishermen, sport fishermen and the community at large, he said, “There’s this feeling that the river just feels different. It feels stronger. It feels cleaner.”

The Klamath is still healing from a century of blockage behind a series of hydroelectric dams, “and the scars are still fresh,” McCovey said. “But the progress that we’ve made in just one year is pretty incredible, and it provides us with a lot of hope for the future.” (To hear more from McCovey, check out the latest episode of the WNYC podcast “Science Friday,” which just came out today.)

While fall Chinook have been an immediate success story, the spring-run Chinook population has a longer road to recovery. It was decimated by a century of blockage. The Klamath’s population of wild spring-run Chinook is down to just a few hundred, Goodman said, adding that the nearby Salmon River hosts one of the last viable populations of spring-run Chinook, and there’s a hatchery population on the Trinity River.

The Klamath’s population of these fish is “on the verge of extinction,” Goodman said, though there is now optimism about its recovery.

“We have a lot of work to do to get spring Chinook back in this river system, but we have an opportunity to do that now with dam removal,” he said.

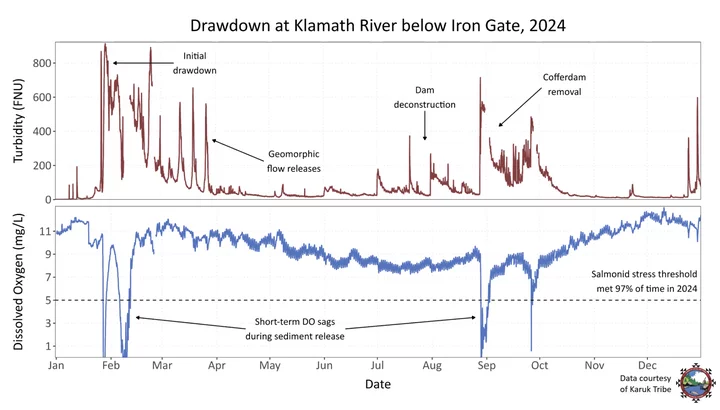

There were major concerns ahead of dam removal about the release of accumulated sediment behind the dams and the resulting effects on dissolved oxygen levels in the river.

Toz Soto, senior policy and research advisor for the Karuk Tribe, said the drawdown was scheduled for last winter to minimize impacts, and while there was a spike in turbidity immediately after the last cofferdam was removed, the water quality quickly recovered.

Screenshot from today’s press conference.

###

“Thankfully, it all worked out in a positive way,” Soto said, noting that there was no large-scale fish kill and the Klamath’s dissolved oxygen levels never rarely fell below the California water quality standard.

Meanwhile, water temperatures in the Klamath have dropped, which is also a positive for fish health. The reservoirs acted as “heat batteries” keeping the water unseasonably warm into the fall migration season, Soto said. The lower temps since dam removal give fish an earlier opportunity to migrate while also improving their health, he explained. The cooler water has reduced the prevalence of toxic chemicals called microcystins, which are produced by algae.

Sami Jo Difuntorum, cultural Preservation officer with the Shasta Indian Nation, focused her comments largely on the impacts to the surrounding landscape.

“We’ve been called the tribe the dams were built on and it is literally true,” Difuntorum said. “The dams were built on our villages.”

When she looked at the landscape immediately after the reservoirs were drained, “It was really stark, really barren,” she said. “Nothing had grown there for, what, 100 years.” While most everyone involved was ecstatic, Difuntorum didn’t immediately share their sentiment. “It didn’t really feel joyous to me,” she said.

It wasn’t until she heard the river rushing through the canyon, hearing rocks popping as water hit them for the first time in 100 years, that she felt happy.

“What it said to me was … the earth and the rocks were welcoming the water back, and so that meant healing,” she said.

Later in the press conference, during a Q&A period with journalists, Goodman said that the Klamath River monitoring work has been impacted by recent federal funding cuts, including the Department of the Interior’s decision to terminate CalTrout’s funding from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

“This loss in funding was a setback for our scientific data collection on the world’s biggest restoration project, but our team is finding other ways to make it work … ,” he said. “While we’re already seeing that the Klamath dam removal is a success, we need consistent and accurate data to understand how much of a success this project was, and we’re currently fundraising to fill the gap for that lost funding.”

Restored landscape in the Klamath River Basin. | Photo courtesy the Yurok Tribe.

Below is a press release with more information:

###

KLAMATH RIVER, Calif. – This October marks the first anniversary since the removal of the four lower Klamath dams, and scientists, advocates and Tribes are celebrating dramatic ecological improvements for the Klamath River. Ongoing scientific monitoring, which started years prior to dam removal, has enabled the documentation of significant advances in water quality, water temperatures, and the rapid return of native salmon populations to previously blocked habitats.

“The Klamath is showing us the way. The speed and scale of the river’s recovery has exceeded our expectations and even the most optimistic scientific modeling, proving that when the barriers fall, nature has an incredible power to heal itself,” said Barry McCovey Jr., Director of the Yurok Tribal Fisheries Department.

News of fish passing the former dam sites came the same week as the project’s completion in early October 2024. While scientists were actively monitoring fish movements and spawning activity in the weeks and months following the restoration of natural flows to the river, it took several months of analysis to finalize specific data related to fish activity above the former dam sites. We now know that more than 7,700 Chinook Salmon swam upriver of the former Iron Gate dam site (the lowermost dam in the system) last fall to access habitat previously blocked by the dams. This number comes from a combination of monitoring techniques, including the use of SONAR, spawner surveys, and redd counts. This year the monitoring continues, and salmon have made it over the Link River Dam into Upper Klamath Lake.

“This is one of the most collaborative and comprehensive restoration studies ever undertaken with agencies, Tribes, and NGOs all coming together to monitor the recovery of the Klamath River salmon post-dam removal,” said Damon Goodman, Shasta-Klamath Director for California Trout. “What we witnessed was extraordinary—the river came back to life almost instantly, and fish returned in greater numbers than anyone imagined.”

Perhaps the most immediate and vital sign of the river’s healing is the dramatic improvement in water temperature—a crucial factor for the Klamath’s ecosystem. The dams and their reservoirs created artificially warm water temperatures in late summer and fall, when fish were returning to the system to spawn, and excessively cold water in the spring, when juvenile salmon out-migrate to the ocean. Ongoing monitoring of water temperatures both pre- and post-dam removal shows that temperatures have returned to a more natural regime that provides improved conditions for salmon during adult spawning migration and juvenile outmigration.

Hand-in-hand with this temperature recovery is a demonstrated monumental improvement in water quality, especially the precipitous decline of harmful algal blooms (HABs) and their associated microcystin toxins. Data collected by the Karuk Tribe since 2006 shows a powerful recovery: while 58% of samples below the former dam once exceeded public health limits, post-dam removal, 100% of water samples have tested within safe limits for people and wildlife. This combination of cooler, cleaner water is creating a resilient, thriving future for both fish and people.

“Since the dams were removed, temperature, algae, and dissolved oxygen levels have all dramatically improved,” said Toz Soto, Senior Policy and Research Advisor for the Karuk Tribe’s Department of Natural Resources. “The process of removing the dams created temporary water quality impacts as sediments impounded by the dams were mobilized through the system. When we look back at the data over the last year, we see that those short-term impacts were worth it, and the immediate improvements to the system are clearly documented in the data collected by the Karuk Tribe and others.”

The first year of a dam-free Klamath River demonstrates a powerful trajectory towards salmon recovery and an ecosystem with significantly improved health with significant cultural and community benefits for Tribes and others in the region.

CLICK TO MANAGE