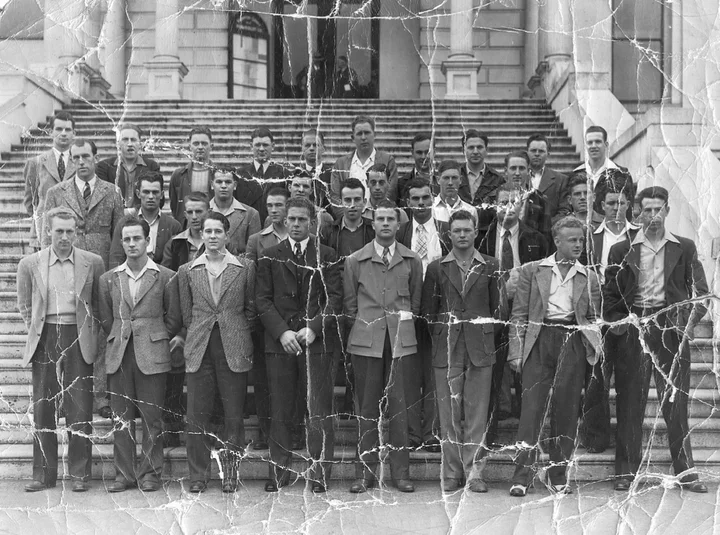

Standing on the steps of the Humboldt County Courthouse, these young Humboldt men have all been inducted into the military on a single day in 1942, following the attack on Pearl Harbor. Phillip died in Humboldt at age 53 from residual complications of meningitis which he contracted during the war. Photos via the Humboldt Historian.

###

Author’s note: This article incorporates quotes about their wartime experiences from letters sent to me over the past two years by several war brides and their children.

###

In August of 1945, a popular song, “My Guy’s Come Back,” filled the airwaves as World War II ended. The guys were not the only ones arriving in America. Some of these veterans brought their brides from war-torn England, France and Italy. Thousands of War Brides arrived in cities and towns all across the United States. They even arrived in the remote, far west city of Eureka.

My cousin, Ray Olsen, brought his bride, Ivy Johnson, known as “Johnny” to her friends in London. Johnny lived in Nottingham, a part of London on the east side of the Thames, within earshot of the Bells of Bow (St. Mary-le-Bow Church), which, it is said, makes one a true Cockney.

In wartime England, all girls of a certain age were conscripted into the military. Johnny was stationed in the main Army Post Office in London. On Thursdays, when the Sergeants Mess served liver and bacon, Johnny and her friend, Betty, ate out. One Thursday they ate at a “palais de dance,” where diners could look down and watch the dancers. Two American soldiers walked up and invited themselves to sit with them. The two Yanks, one of whom was Ray Olsen, wanted to pay for the girls’ dinner, but Johnny said, “No way! We pay for our own, thank you,” and sent him packing. Like other English girls, Johnny had been warned by her mother and grandmother to stay away from the American soldiers. The older women remembered stories about Yanks during the First World War wanting only sex and a good time.

Left: Ivy “Johnny” Johnson of the English Army Postal Service and U.S. soldier Ray Olsen of Eureka in Nottingham at the Sergeants Mess. It is a Sunday, the only day the girls in the English Service were allowed to wear civilian dresses. Johnny wears a dress she made herself, for precious ration coupons were required for the purchase of clothing.

Ray Olsen persisted in his courtship of Johnny, and by the end of 1945 they were married. Johnny, the youngest of ten children, said a tearful good-bye to her family on a cold and rainy morning in March, 1946. She crossed the Atlantic with several other war brides, all of whom shed many tears on the trip. After the ship docked in New York Harbor, the girls took a train to the West Coast, with a three hour lay-over in Chicago.

For three and a half years, Johnny had had nothing to wear but austere uniforms and sensible shoes. In Chicago, she spotted a Marshall Fields store, a place she had heard of but had never seen. Imagine her excitement when she walked through its doors to find pretty shoes and clothing. Johnny bought three pair of high-heeled shoes, and then hurried to catch her train to continue her journey across the continent of North America.

###

Another war bride, Lou McCornack Butler writes: “Ten long years brought an end to a path of destruction and horror such as the world had not anticipated. Thousands of young women found themselves carried forward on a tide of change … Married to World War II [American] servicemen, they became voyagers to a new land and new customs … Would they fit in? Would they measure up?”

When Lou left England at the age of nineteen, she had already lived a lifetime of changes. Lou had been raised on the Southwest side of the Thames, near the old Lambeth Church, Smith’s bookbinding, and the Doulton china factory, where her grandfather had been apprenticed as a boy. She worked at the ivory factory of Puddefoot and Bower, which had been converted to produce airplane rivets during World War II.

At night she served as an air raid warden. Lou married John Edward Campbell, a member of the King’s Royal Rifles and part of the original Scottish Black Watch. Lou had given birth to her first child, Rosina, during an air raid; she had had to search for family members in the rubble after a London bombing; and her husband, John Campbell, was killed on D-Day, leaving Lou an eighteen-year-old widow with a little girl.

At this time, the British and Hollywood movie star, Madeleine Carroll, turned her home on Mansfield Street in London over to the United States servicemen while she went to France to work with the Red Cross and help war orphans. Lou and her mother both worked part time as housekeepers at this house, known as the American Officers Mess. Lou had charge of three apartments: one for a major, and two for generals — General Patton and General Scott — and found it interesting to see these famous men at ease.

Phillip McCornack was Mess Sergeant of the American Officers Mess. He had been rescued from his torpedoed ship during the African campaign and was recovering from meningitis. His normal weight of 160 pounds had dropped to 80 pounds. Lou’s mother felt sorry for this young man and invited him home for dinner on weekends. Lou, like Johnny, had been warned against American servicemen and announced that she would not stay in the house while that Yank was there; however, her father said that as long as she was under his roof, she would be courteous to their guests.

Lou and Phillip were soon dating. Lou’s father always waited up for them, expecting them before the 10 p.m. curfew. The couple would come home to find him standing on the porch with his watch. If it was five minutes after ten, he would say, “You’re late.” Phillip would reply, “I’m sorry” and explain there had been buzz bombs. When you heard the jet engine cut out of what sounded like a plane overhead, it meant a buzz bomb was coming down. Lou recalls that 50,000 people died in bombings over just one weekend in London. At one point, all the buildings around St. Paul’s Cathedral burned, but the Cathedral remained intact. Lou remembers Winston Churchill saying: “We cannot let it burn. It is a symbol of our heritage.”

By the time Phillip was sent back to America, he and Lou had been married a year. Before Lou left for America, her mother warned her about the United States, as she understood it: “Be very careful of New York, because there are gangsters there. In the middle, that is the real America, with homes and families. Be very careful when you get to the west; there are cowboys and Indians.” It took a visit for Lou’s mother to appreciate what America was really like. Then she said, “God has truly blessed America.”

Lou writes: “Some of the war brides crossed the Atlantic on the Queen Mary and other such vessels, but the group I came with boarded a Merchant Marine ship, the Henry Gibbons, with metal bunks three tiers high close together in the cargo hold, damp and cold with the constant noise of engines day and night. I always felt that I could hear the sound of muffled crying and a sense of fear and sadness.” Lou was seasick the whole time of the Atlantic crossing. Her group was the last to go through Ellis Island before it closed. Their names are on the wall for the year 1945.

In 2003, Lou discovered that the merchant ship she had traveled on for eight days, avoiding mines, freezing in the cold and damp, had originally been converted to carry one hundred sick and tortured refugees from Nazi prison camps. “I can only imagine their fears and sorrows being taken to an unknown country after all they had suffered,” writes Lou. “I felt that I had truly been touched by sharing their space.”

###

Joyce Ratcliffe and a girl friend had walked across the moors in northern England during the blackout to attend a “picture show” in Manchester. While standing in line for their tickets, she met an American soldier, Murl Francis Bryan, of the Eighth Army Air Corps. Joyce remembers complaining about the American soldiers taking all the spaces. The picture that night might have been an Alice Fay movie. Joyce notes that she would have remembered if it had been a Betty Grable picture, because Murl always said her legs were just like the movie star’s. Betty Grable’s “pin-up legs” were famous for being insured by Lloyds of London for one million dollars.

When Murl was off duty, Joyce rode her bicycle over the moors to meet him. They decided to marry, but before the wedding, Murl’s chaplain and his commanding officer interviewed Joyce. They warned her that Americans lived in a very different way than the English, and that she was a city girl while Murl was from a rural area. The chaplain pointed out that not many couples successfully overcame these “cultural differences.” Murl’s family had lived in Missouri, but had moved west during the Depression and settled in Miranda, California. Joyce and Murl compromised by moving to Eureka — neither in the country nor in a big city.

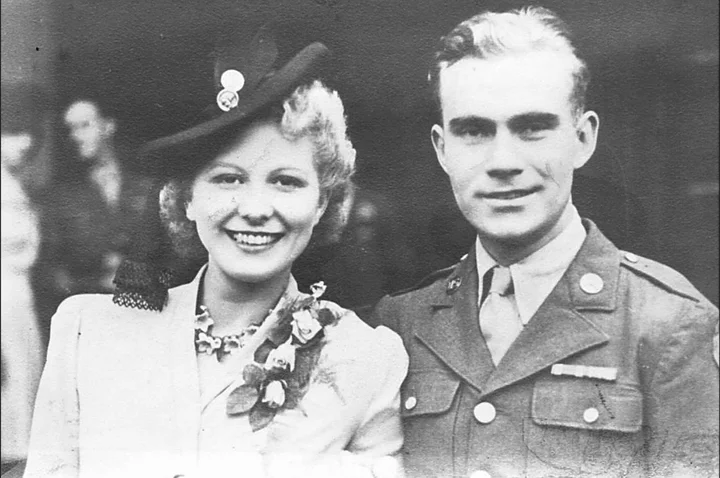

Joyce and Murl Bryan on their wedding day in Lancashire. Their marriage ended much too soon: Murl died of a heart attack at age thirty-nine.

Joyce managed to collect enough ration coupons for a wedding dress.

“I didn’t want the ‘wreath and veil,’ what we called the traditional gown,” writes Joyce. “I wanted a dress I could wear afterwards, because I didn’t have a lot of clothing coupons.” The dress was light beige-pink. Shoes were harder to find. “We were lucky when it came to the wedding cake,” Joyce said, “as my cousin Gilbert was a baker.”

They were married on Joyce’s nineteenth birthday, on Thursday, September 1, 1944, at St. James Church in Oldham, Lancashire, England. The church stood just in front of the Platt Company, where Joyce worked. All her friends hung over the wall cheering as they left the church.

Paris had been liberated by the Allies a month before their wedding, and a month afterward, the Warsaw Uprising took place. Vera Lynn, known as “The Armed Forces Sweetheart,” was the most popular female vocalist in England with songs like “We’ll Meet Again,” and “The White Cliffs of Dover.” The big band sounds of Glen Miller and Benny Goodman were popular everywhere. The classic song, “Lili Marlene,” was a favorite with soldiers on both sides of the war — the Allies and the Germans — as it had been during World War I.

Joyce traveled to the United States two years later with her baby daughter, Lesley. Lesley writes, “Joyce started her journey to this country in late June of 1946, arriving sixteen days later on July 10. With only the few belongings allowed by the U.S. Army, and with her ten-month old daughter tucked under her arm, Joyce gamely strode up the gangplank of the Zebulon B. Vance to embark on a new life in a new country. As if immigrating to America was not challenge enough, Joyce had no idea that the ship she and her little daughter were boarding was one of the most controversial and potentially dangerous ships in the fleet of converted Liberty Ships dubbed by the New York press as the “Bride Ships,” and later called by its own crew “the death ship.”

Joyce herself writes: “Conditions were awful. Bunks were stacked three high all in one large room. There were far too few toilets for the number of passengers and absolutely no privacy as they were in open rows. They constantly overflowed and the women had to walk through the waste to get to one of the four showers, not curtained, for water or a wash. Many were so seasick they could not move. Vomit floated on the floors and had to be wiped off the bunks. The crew tried to keep things mopped up and some of the women tried too, but it was nearly impossible.” Some reports state nurses were on board, but Joyce never saw one.

For some strange reason, baby food was confiscated upon boarding, but Joyce hid Lesley’s because her baby had to have a certain kind, and she was afraid she might not get it back. She washed her baby’s bottle and nipple in the hot tea water and also used that boiled water to make her formula. Baby Lesley lost four pounds in sixteen days.

The women were subjected to “flashlight exams” for lice and venereal disease. Joyce writes: “These exams were often performed by non-medical personnel, in the open, and frequently included humiliating and offensive remarks.” She recalls that when a U.S. Army officer was questioned about these exams in 1946, he replied to the effect that these women weren’t asked to marry our guys and come over. He was wrong about that: the girls had been asked by the men they married to be their wives and come to America.

The New York Times published this photo of Joyce Bryan, wearing her identification tag, and her baby daughter, taken the day of their arrival in New York Harbor, with the caption: “TINY SOPRANO, Darlene [Leslie] Bryan, 10 months, gives out with blues number, accompanied by Mrs. Joyce Bryan.

Finally, on July 10, 1946, the Zebulon B. Vance steamed into New York Harbor and was met by a reporter from the New York Times. He interviewed Joyce, and took a photograph of her seated at an upright piano with the baby sitting on top of the piano, crying. At least nineteen babies had died on this trip, due to the unsanitary conditions. The surviving babies and women were all tagged like pieces of luggage, and told they had to board a bus, probably for the Red Cross Center, where they would be reunited with their husbands. But Joyce had seen her husband, Murl, the love of her life, standing on the dock, wearing a light gray suit. This was the first time she had seen him in civilian clothes. A crewman told her she had to go with the other brides to the bus, but she told him her husband was waiting right there for her and nobody was going to stop her from going to him. Holding little Lesley, she walked right off that ship and into his arms.

The women had been cautioned to dress warmly as it might be cold (New York City in July?), so Joyce wore a red wool suit in 100 degree weather. The first thing she and Murl did was go to the bank where Joyce had had money transferred from England, then to a drug store for cream for the baby’s rash, and finally to a shop for a few cool summer dresses. This done, they boarded their train for San Francisco.

###

Johnny’s and Lou’s husbands met them in San Francisco. Ray Olsen met Johnny at the train station, and they drove up Highway 101 to Eureka, a ten-hour trip in 1945. Johnny didn’t know what to expect. The redwood trees were magnificent and the rugged beauty of the country awed her, but Humboldt County was a totally different environment from her home in London.

Lou and Phillip spent one night in San Francisco, and then drove to Eureka. Lou remembers feeling “loneliness, a separation from loved ones … Like most I was pregnant immediately.” She wrote to her mother about her feelings: “It’s very nice, but this must be the end of the world because the railroad ends here. It doesn’t go anywhere further. The ocean goes off to Japan and there’s no theater, no ballet.”

Her mother replied, “My dear girl, we love you, but you chose your bed, now make it as comfortable as possible, it’s up to you. God Bless you all.” Lou says it was the best advice of all.

When Ray and Johnny arrived in Eureka, my mother, Laura Olsen, invited them to dinner at our house. Before the war, Ray, as a teen-ager, had worked in my father’s auto repair shop. Here Ray had learned skills from my father, Mike Olsen, that enabled Ray, with his natural talent for things mechanical, to help keep the bombers flying over Germany during the war. My father had died the previous December of cancer. Johnny told us that when Ray received this news in England, it was the only time she had seen him cry. Mike’s girls — my mother and my sisters and I — welcomed Ray and Johnny to Eureka.

Later, as more war brides arrived, we would have little parties for them. One time I tried to be helpful and make tea in a land of coffee drinkers. I put loose tea leaves in my mother’s antique bone-china tea pot and poured hot water over it. The result was the way I liked tea, if I ever drank it — pale-colored water. But the English girl for whom I had made the tea couldn’t abide it. I later learned that English tea is strong and dark. Lou McCornack Butler recalls her father saying: “If you can see the bottom of the cup, it’s water bewitched and tea begrudged.”

Joyce Bryan writes about her arrival in Eureka: “We were all warmly welcomed by the community and I was eager to learn all about Eureka and Humboldt County.” Joyce and Murl took baby Lesley to beaches on the Eel River near Miranda and Garberville. Joyce was impressed with the Redwoods. The climate in Eureka agreed with her, as it was much like the climate in England. “It was actually very pleasant to walk to visit each other in our homes, pushing our baby buggies. We walked often to Sequoia Park.”

There were many new American words for everyday things, such as buggy for “pram” and drugstore for “chemist.” The English girls sometimes made comical or embarrassing remarks by using British words or expressions that meant something else in America; for example, to be “knocked up” in England meant to be awakened by the “knocker-upper,” whose job was to awaken people for work in the morning by rapping on their windows. The girls quickly learned that it meant something different in America.

Johnny Olsen will never forget her wonderful neighbor, Mrs. Del Dotto who taught her how to cook and to care for her small children as they arrived over the years. “She was always there for me,” says Johnny.

Johnny will also never forget her first washing machine. It took a while after the war for factories to gear up to civilian needs again. Up until then she had had to do laundry by hand with a scrub-board. “Disposable diapers?” she queried. “I think not.”

###

Not all the war brides who came to America stayed. Anna Maria Albonetti was nineteen when she met American serviceman Raymond Hull in Rome. She was standing on her terrace when Raymond stopped to speak to her. Anna Maria did not speak English, but somehow they managed to communicate with each other. At the time, she was engaged to her childhood sweetheart, but “the blue eyes of the American soldier changed her mind.” Her parents convinced the couple to postpone marriage until after the war. Anna Maria then joined Raymond in Eureka, traveling by air to New York City and then by train to Oakland, California. They were married in San Francisco and drove to Eureka, where their children, Vincent and Pamela were later born. But in 1959, Anna Maria decided to return to Rome, “the eternal city,” with her children. In 1973, she remarried, to a widower. Her new husband was her former Italian fiancé, her original childhood sweetheart.

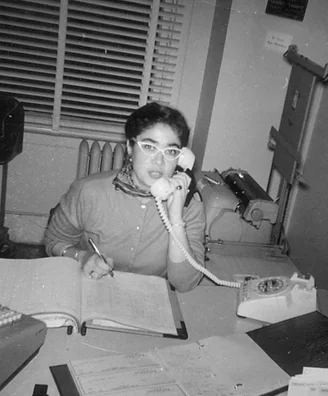

Although she didn’t stay, Anna Maria has many wonderful memories of her life in Eureka and still keeps in touch with the friends she made here. She improved her English by borrowing books from the Eureka Carnegie Library, and became secretary to lumber businessman Kelton Steele. “This was the job anyone could desire,” writes Anna Maria. “I was the office manager of the Western Timber Company and although in Italy I didn’t know how to add one to one, they gave me a chance, and I learned to be a good bookkeeper… I also had some wonderful colleagues, besides a very dear boss, Kelton Steele, who always showed to be very satisfied of my work.” Anna Maria writes of the following memorable experience:

“The most wonderful thing happened to me while living in Eureka. [One day] … instead of going out to lunch, I stayed in the office reading The Wall Street Journal while having a sandwich. The Federal Housing Administrator was looking for one hundred housewives wishing to write to him telling about their ideas concerning what they would like their house to be. I said to myself: I have some ideas about this! And I wrote my letter. Only a few days later I was called from Washington D.C. to inform me that I had been selected for the First Congress on Housing.”

Anna Maria received an airline ticket for the capital, and her boss gave her fifty dollars expense money. She spent a little of the money for a white gardenia to wear on her suit.

“It was a wonderful experience. We were brought to the President’s studio [oval office] inside the White House, and had the honor to meet with Mrs. Eisenhower. Only in America could something like this happen to an ordinary person. I am still very proud to be an American citizen.”

###

The World Friendship Club holds its first official meeting at the YWCA in 1947. President: Joyce Bryan Von Strahl; Secretary: Rene Eyler; Treasurer: Jimsky Butterfield; Publicity: Lou McCornack Butler. From left: Anastasia (Mrs. Alfred) Barthelemy; Jeannette (Mrs. William R.) Zerlang; Simone (Mrs. Clyde F.) Sadler; Maria (Mrs. Thomas) Bascomb; Mrs. Louis DeRoos, Eureka advisor; Lou (Mrs. Phil- lip) McCornack Butler; Joyce (Mrs. Murl) Bryan Vonstrahl; Rene (Mrs. Frank) Eyler; Jimsky (Mrs. Wil- liam) Butterfield; Joan (Mrs. Frederick) Printy; Irene (Mrs. James) Riley; Ivy “Johnny” (Mrs. Raymond) Olsen; Ursula (Mrs. Kermit) Ostrander; Elsie (Mrs. Benjamin) Young.

Lou Butler soon realized that there must be other war brides like herself in Eureka who were lonely. She and another English bride, Elsie Young, gathered names of eighty-two “aliens” like themselves. At first they went door to door. They telephoned. Then, with the help of Fred J. Moore, Jr., County Clerk, they recruited as many war brides as they could find. In 1947 the girls organized a charter group of The World Friendship Club under what Lou calls the “loving wings” of Mrs. Katherine Shattuck, director of the YWCA. While the club originally consisted of war brides, it soon opened up to any foreign-born bride.

“A lot of people came over afterward, but weren’t necessarily what you’d call war brides,” said Jeannette Zerlang in a November 2, 1997 Times-Standard interview. Jeannette was a war bride from France who married Army Sergeant William Zerlang, on May 17, 1945.

Lou Butler writes: “Jeannette Zerlang was from Alsace-Lorraine [and] part of the French Underground.[She had] incredible ‘joie de vivre.’ [She] insisted her name be spelled ‘avec deux n,’ and began all our Christmas parties with ‘Zh-h-h-ingle Bells.’ We mourned our sister when she took her final voyage in 2004, but heaven will ring with Zhingle Bells!”

The World Friendship Club held meetings once a month and put on shows and rummage sales. The money earned was donated to local charities such as Seeing Eye Dog organizations and orphan advocacy groups. They also raised money for the “Y” by preparing card parties, tea parties, and international dinners.

One time the girls dressed a beautiful doll in a coronation outfit complete with a crown, orb and scepter. The doll and her collection of costumes representing all the countries the girls came from were fitted in a wooden wardrobe. This was raffled and the funds given for equipment for children with hearing problems. As “aliens,” they took classes with those who needed to learn English, helping each other and learning American History in order to become naturalized citizens. Later, when most of them had little children, they still did their part, working the first March of Dimes fundraiser in Eureka, door-to-door with babies in buggies.

Local and national politics came to their attention and they helped with campaigns. They petitioned the city to resurface a local tennis court and succeeded in this mission. They were involved with PTA and school activities and civic matters. Their families grew in size until the meetings overwhelmed the YWCA facilities. The girls decided their husbands would have to recognize women’s rights and babysit one night a month so that they could meet as a group.

Lou writes: “Not all the original members attended every time, and some moved away, lifestyles changed, but we all remained friends. We became a band of sisters … we were all so different, yet so much alike. We helped each other through bouts of homesickness, pregnancies, and emergencies … We spoke of families, loneliness, children and ‘back home.’ We lamented customs we did not want to lose … We shared memories of childhood and how much we had in common although we had grown up thousands of miles and half-a-dozen languages apart across the world. We spoke of the war and knew … when the battle is over, there are no enemies, only sisters. Johnny Olsen was our in-house piano player and we sang all our native songs and danced; and laughter healed our hurts and gave us support.”

Of her life since she became a war bride, Johnny writes: “I am happy to say my husband Ray and I have been married for sixty years. [Ray Olsen died in 2006.] We have visited my family in England many times and have attended reunion functions of “The 95th Bomber Group,” with whom my husband served and was stationed at Horham, England. We both know most of the residents, and they welcome us back each time with open arms. They go out of their way to entertain us to show their appreciation of what ‘the Yanks’ did to help end the war in England. They will never forget it, nor will I. Ironically, created by a devastating war, my new life went on to become some of my most memorable and happy years that I have ever spent. The connections I have had with the other war brides are very special to me. Looking back, I don’t t hink I would change a thing.”

Joyce’s daughter, Lesley, writes about her mother: “I am the daughter she brought on board [the Zebulon B. Vance] and whom she kept alive and well through a small but significant act of defiance [hiding her baby’s special food] … Although she endured humiliation, filthy and unsafe conditions, and sixteen days at stormy sea, Joyce … never considered even for a moment, anything other than a positive outcome.”

“We did not come to America looking for a hand out,” concludes Lou Butler, “but like early immigrants before us, we came with hands out ready to become part of a great nation. I think that most of us who stayed have proved that the choices made by those young men we married over sixty years ago, were good choices.”

The World Friendship Club celebrates its sixtieth anniversary this year.

###

The piece above was printed in the Fall 2007 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE