OBITUARY: Constance ‘Connie’ Heberly Higgins, 1942-2024

LoCO Staff / Saturday, Oct. 5, 2024 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Constance ‘Connie’ Heberly Higgins peacefully passed away on

October 2, 2024 in Eureka at the age of 80.

Connie was born into the family of Les and Sanna Heberly on October 4,1943 in Portland, Oregon. The family moved to Arcata in 1951. She was the first born of three children.

Connie attended Arcata schools, graduating from Arcata High in 1961. She attended Humboldt State College and began a banking career in Arcata. She started her banking career as a teller working her way up the ranks to a regional manager in the San Francisco East Bay area, settling as a bank manager in Concord. She eventually moved back to Arcata and took a job as head cashier at Humboldt State University, where after several years, she retired and enjoyed domestic and international traveling. Connie enjoyed many years of competitive shooting and was also a member of the Soroptimist International of Arcata.

Connie is survived by her son: David Lusty (Diane) of Grants Pass, Oregon; four grandchildren Jacob Lusty (Hayley), Caleb Lusty, Claire Rasmussen (Jacob), Hannah Saulovich (Shon Jr.) and three great-grandchildren: Emmerson, Roxie and Ruth. Connie is also survived by her siblings: Pat Durbin (Gary) of Arcata, and Kirk Heberly (Deborah) of Blue Lake.

As a Christian believer Connie attended churches in various places where she lived.

There will be no public service.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Connie Higgins’ loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

BOOKED

Today: 6 felonies, 11 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Today

CHP REPORTS

Boulder Rd / Railroad Ave (HM office): Traffic Hazard

Us101 S / Fields Landing Ofr (HM office): Provide Traffic Control

ELSEWHERE

Governor’s Office: Governor Newsom honors fallen San Joaquin County Sheriff’s Office Sergeant

Governor’s Office: Governor Newsom’s schedule for February 25, 2026

RHBB: Two-Vehicle Crash Blocks Lanes at G Street and Samoa Boulevard in Arcata

RHBB: Harbor Lanes Temporarily Shut Down by Health Officials, Reopens After Fixes

Looking to Recover From Scandal, Alan Bongio Seeks Re-election to Humboldt Community Services District Board

Ryan Burns / Friday, Oct. 4, 2024 @ 3:46 p.m. / Local Government , News

Two years after derogatory and racist remarks derailed his local political career, construction company owner Alan Bongio is hoping to regain a seat on the Humboldt Community Services District’s board of directors.

Bongio is one of four candidates running for three available seats on the government agency, which provides water distribution and sewer collection services for the greater Eureka area, including Freshwater, Fields Landing and Humboldt Hill.

The other three candidates — Heidi Benzonelli, Joe Matteoli and Michael Hansen — are all incumbents seeking re-election.

Bongio served more than two decades as an elected member of the HCSD board and 10 years on the Humboldt County Planning Commission (many of them as chair) before finding himself embroiled in scandal over his behavior during the Planning Commission meeting of Aug. 18, 2022.

In a hearing to consider permit violations on a doomed mansion-building project off Walker Point Road, Bongio railed against interference by “the Indians,” referring to objections that had been raised by both the Blue Lake Rancheria and the Wiyot Tribe. He went on to accuse tribal representatives of lying and manipulating the process. At one point he appeared to invoke a racist phrase by alleging that the tribes had gone back on an agreement, saying, “I have a different term for it but, you know, whatever.”

His comments sparked significant offense among local tribe members and the broader public. Wiyot Tribal Administrator Michelle Vassel described the proceedings as “a shocking abuse of power and display of discrimination,” and the tribe later filed a formal complaint.

Bongio argued that his remarks had been misconstrued and that the term “Indians” is not considered offensive by many Native Americans. But the scandal did not go away. The following month, the Board of Supervisors unanimously censured Bongio and asked him to step down as chair.

The following November he lost his seat on the HCSD board, placing third in a race for two available seats. Shortly before Christmas of 2022, Humboldt County Supervisor Rex Bohn, who had appointed his friend to the Planning Commission a decade earlier, announced that Bongio had resigned.

Reached via phone on Friday, Bongio said he’s running again “because I spent 21 years there and I feel that I bring a lot of knowledge to the position.”

He also said he doesn’t agree with the current board on certain decisions, including a big rate increase passed via a 3-2 vote last year.

“I’m not denying that [rate increases] need to happen, but a 112% increase on connection fees is ridiculous,” he said.

The rates approved by the board call for an increase of 88% over a five-year period, but Bongio said he’s aware of one proposed project, a 34-unit apartment complex, that had its quoted rate more than double under the new charges.

“It has all but shut down development in the district,” he said. “There have been only two permits taken out this year because [developers] can’t afford to make it happen. They [the district’s board] have made it too expensive.”

HCSD General Manager Terrence “T.K.” Williams told the Outpost that Bongio appears to have gotten that “two permits” figure from a report covering only July and August of this year. The full annual report, listed on pages seven and eight of the board’s Sept. 10 agenda, show that the connections have not dropped dramatically.

“In the year and two weeks since the capacity charge increase, there have been 11 new water connections and 12 new sewer connections,” Williams said via email. “This is statistically similar to every one of the past ten years of new connection data for the District.”

It’s actually below the average of 15.8 water connections and 15.4 sewer connections, based on the numbers provided, but the figures are within the range of year-to-year fluctuations.

Regarding the rate increases, Williams said the district approved them at the end of a two-year process that included “multiple public workshops,” following guidelines from the American Water Works Association and the recommendations of a rate study consultant “who is an expert in the field.” (The consultant’s water rate and capacity charge study can be found here.)

Williams said rates vary from one project to another.

“The current capacity charges are higher than they were before September of 2023,” he said. “[Whether] they increased by 112% is difficult to say because the District changed how capacity charges are calculated; I can’t confirm or deny that value. The increase varies depending on the specific situation.”

Regardless, he said the rates are based on the amount necessary for the district to cover expenses. In other words, capacity charges reflect the calculated cost to buy into the system.

“If capacity charges are set lower than what is recommended by the American Water Works Association Model, the rate payers are subsidizing new construction and development,” he said.

Members of the HCSD board receive $100 for each regular meetings and $50 for any ad hoc meetings or when representing the district with other boards, such as those of the Redwood Region Economic Development Commission (RREDC) and the Humboldt Local Agency Formation Commission (LAFCo).

Directors also receive health, dental and vision insurance, an employee assistance program and a $10,000 life insurance policy. Last year, the five board members’ wages ranged from $2,050 to $3,150, and the value of their benefits packages ranged from just over $10,000 to $41,581, according to data from the State Controller’s Office.

We asked Bongio if he has anything to say regarding the end of his term on the Planning Commission and the scandal from two years ago. “I don’t have anything to say,” he replied. A beat later, he added, “It’s called liberalism.”

Bongio declined to say anything further while on the record.

###

Note: This post was updated Oct. 5 to add more specifics about the district’s annual water and sewer connection numbers.

###

PREVIOUSLY

- Heated Meeting Sparks Accusations of Dishonesty and Discrimination, Opening Rift Between Tribes and Humboldt County Planning Commission

- Despite Silence From Tribes, Mega-Home Builder Optimistic Ahead of Tonight’s Continued Planning Commission Hearing to Address Permit Violation Fallout

- After Rebukes and Apologies for Bongio’s ‘Disrespectful’ Comments, Planning Commission Defers Decision on Mega-Home Permits

- County Supes to Consider Censure of Planning Commission Chair Alan Bongio for Inappropriate Conduct

- Bohn Makes the Motion, Supes Unanimously Censure Bongio for Racist Remarks, Move to Remove Him as Chair of Planning Commission

- Bongio to Step Down as Chair; Planning Commission Set to Consider Apology for His ‘Insensitive, Racist’ Comments

- Bongio Steps Down From Chair Position; Planning Commission Approves Apology Letter for Racist Comments

- Alan Bongio, Embattled Humboldt County Planning Commissioner, Resigns

Eureka and Arcata Tie for No. 1 Spot in L.A. Times Ranking of Best Places to Retire in California

Ryan Burns / Friday, Oct. 4, 2024 @ 10:22 a.m. / News

California’s crown jewels. | Arcata photo by hakkun CC BY-SA 3.0; Eureka photo by Pamla J. Eisenberg CC BY 2.0.

###

Prepare for a silver wave of incoming retirees, Humboldt! Today, the Los Angeles Times, California’s largest newspaper by circulation, released its rankings of the top 10 best places to retire in the state, and behold! There’s a two-way tie atop the podium: Our very own Eureka and Arcata.

How the heck did they arrive at that conclusion, you ask? The Times ranked 367 California cities based on four criteria:

- Climate: the number of days of extreme heat expected per year, based on projections for 2035 to 2064

- Health and wellness: a health index combining dozens of factors, including air quality, access to transportation and proportion of adults with health insurance — though not direct access to hospitals [emphasis added]

- Recreation: the proportion of residents who have a park, beach or open space greater than 1 acre within a half-mile of their home

- Affordability: typical home prices and rental costs in the city

As such, our local municipalities benefited from having zero days per year above 100 degrees; copious access to parks, beaches and open spaces; and relatively cheap home and rent prices (by California standards, anyway).

Both Eureka and Arcata also rate near or (in Arcata’s case) above the top 50% in the health index.

The list notes one specific “con” for our local cities: their remoteness, which some of us consider a “pro.”

“A drive from Los Angeles would take nearly 11 hours, and that is without any traffic (good luck with that!),” the story says. (Who the hell drives from here to Los Angeles? We have direct flights, ffs.)

Our neighbor to the north, Crescent City, lands at No. 7 on the list despite having “few attractions” and ranking “poor” (bottom 20% of all cities) in the health index.

The Bay Area also makes a good showing, with Benicia and Emeryville making the list. Also in NorCal: Fair Oaks in Sacramento County and the picturesque burgh of Grass Valley in the Sierra Nevada foothills.

GUEST OPINION: Please Think Twice Before Voting For New Sales Tax Hikes That a Lot of People Can’t Afford

Enoch Ibarra / Friday, Oct. 4, 2024 @ 7:30 a.m. / Guest Opinion

I’m not in the habit of sharing or discussing my political opinions and, in fact, try to remain mostly apolitical in my views.

I don’t know how a large portion of the population in Fortuna, or in our County, that lives paycheck to paycheck, or this is on a fixed income, can afford to live, given the inflation that continues to affect food prices and other of life’s necessities.

Our City Council recently enacted a 50 percent increase on our sewer and water fees and has advised of a further 50 percent rate hike.

Given the state of our economy and the financial struggles that many people are currently facing, I am pretty fed up.

This comes at a time when my own home and auto insurance rates have been hiked by nearly 100 percent to fill the losses experienced by the insurance industry in this state, and to ensure comfortable retirements for insurance industry officials.

Additionally, my health insurance company just informed me that their rates will increase by 20 percent in January.

Oh, and I haven’t even mentioned the recent PG&E rate hikes and gasoline tax increases.

The cost of living continues to increase and Fortuna’s ballot Measure P seeks to increase it further if it passes this November.

Measure P is asking Fortuna citizens to approve an extension of Measure E taxes (approved in 2016), and in addition an increase of .075 percent. That increase — along with the county’s current tax proposal, Measure O, of an additional 1 percent tax – would, if both are approved — cost citizens over 10 percent in taxes on all taxable “retail” purchases.

Measure E is supposed to sundown (expire) after eight years; this measure proposes to extend and increase this “special” tax through March 2033.

City staff and the recent former city manager made recommendations to our City Council to raise taxes to fill budget shortfalls by not allowing Measure E to sundown. That is usually the way taxes work— they seldom go down, but often a way is found to raise them

Now the interim city manager, police chief and at least one city council member are campaigning to fill a projected shortfall of more than half a million dollar in public work funds – funding that they should have known, or did know, that they would need. Additionally, they are looking to create a third park along the Riverwalk on property purchased recently, along with numerous other projects that are in their vision of what our City should have.

According to open-source information, not long ago the city of Fortuna received $2.9 million in COVID-19 funding (euphemistically named the American Rescue Plan Act funds), of which $2 million apparently went to build a new police station. I am not sure where the other $0.9 million went.

I recall a recent ex-mayor saying, not long ago in a City Council meeting, that when her children ask for something and the money isn’t there that she tells them to make do. That is probably what most reasonable people do.

In my opinion these initiatives are being championed by some people who do not and have not lived in our community, but who will benefit from these additional taxes.

I am not ready to vote for an extension of this tax, nor do I support an increase without much more transparency on how these funds are being spent, and will be spent. Vague promises just don’t cut it for me.

The current Measure E taxes were promised to fund public safety ,which most citizens translated to mean police services. However, that is not the vision that our politicians had in mind. I guess just about anything can become a matter of public safety if you label it as such.

Also, please understand that none of those funds will go to our local Fire Protection District. Some will certainly go to the police department, but where will the rest of the funds go?

It is my opinion that many people just glance over their voter information packets and vote mostly on emotion, or on what a friend or relative has told them is best.

I urge you to please take the time to ask questions and inform yourself, think about the consequences of what you are voting for and make the most informed decision that you can make.

As for me, I will vote NO on both Fortuna’s ballot Measure P and the County’s proposed Measure O tax increases.

Enoch

Ibarra

Fortuna

‘Beyond Cruel’: Newsom Retaliates Against This LA Suburb for Its Ban on Homeless Shelters

Felicia Mello / Friday, Oct. 4, 2024 @ 7:30 a.m. / Sacramento

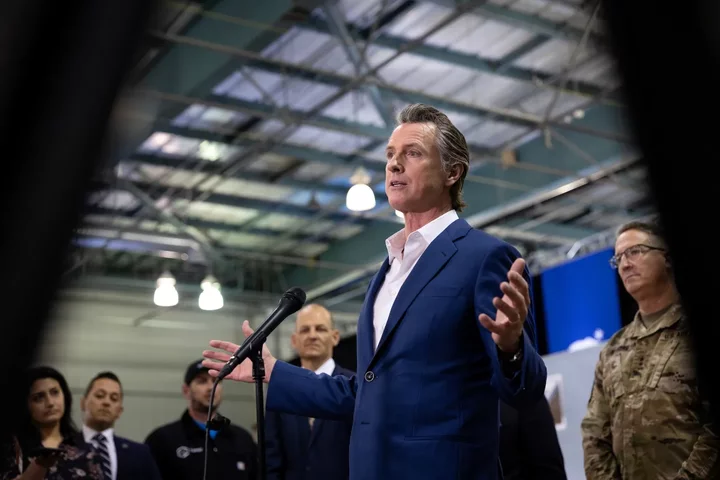

Flanked by state and local politicians, Gov. Gavin Newsom announced the state’s plan to address homelessness across the state at Cal Expo in Sacramento, on March 16, 2023. Photo by Miguel Gutierrez Jr., CalMatters

The mayor of a middle-class Los Angeles County suburb said the city stands by its moratorium on homeless shelters and supportive housing even after facing state sanctions.

California’s housing department revoked approval of the state-mandated housing plan for Norwalk, a city of just over 100,000 people with a homeless population of at least 200 according to county data. The move — the latest escalation of Gov. Gavin Newsom’s pressure campaign on cities to help solve the housing crisis — means Norwalk could lose eligibility for state housing and homelessness grants, and be forced to approve affordable housing projects even if they conflict with city zoning.

The city council passed the temporary but sweeping ban in August, in the process quashing a county effort to resettle dozens of people living in encampments to a local hotel. After the council doubled down on the ban last month, extending it through August 2025, Newsom clapped back.

“It’s beyond cruel that Norwalk would ban the building of shelters while people are living on the city’s streets,” Newsom said in a statement yesterday.

Norwalk Mayor Margarita Rios told CalMatters the moratorium came about in part due to city leaders’ frustration with an earlier state-funded temporary housing program, Project Roomkey, that housed formerly homeless people in the same hotel during the pandemic. She said the county hadn’t provided sufficient support for the unhoused people from Norwalk and elsewhere who filled the rooms.

“They were vacating their room with no after-care, no follow-up,” she said. “They went back out where they started, back onto the streets of the city.”

But rather than targeting a specific project, the city council enacted a wholesale pause on emergency shelters, single-room occupancy hotels, supportive housing and transitional housing — along with liquor stores, discount stores, laundromats, car washes and payday lenders. Rios said those businesses “just didn’t fit in our economic development plan.”

The “unusually far-reaching” nature of the measure likely drew the attention of state leaders, said Chris Elmendorf, a law professor at UC Davis who specializes in housing and land use.

“It seems like what Norwalk did here was try to pass an ordinance that not only banned homeless shelters, (which) they’re not allowed to do, but tried to ban any business that provides services to poor people,” he said.

California cities are navigating a new legal landscape in the wake of a U.S. Supreme Court ruling this summer that gave local governments more power to arrest and fine people sleeping outside. Newsom has pushed city leaders to clear encampments and rehouse their occupants, with some embracing the task and others resisting what they see as a criminalization of homeless people whom the state has not dedicated sufficient resources to house.

The crackdown on Norwalk, said Elmendorf, could represent a warning to cities that simply trying to chase homeless people to the next town over will not pass muster.

Among other bare-knuckle tactics in its battle against the housing crisis, California reached a legal settlement with the Sacramento suburb of Elk Grove last month requiring the city to approve additional affordable housing, and secured a court order in May forcing Huntington Beach to plan to build more homes, though a judge stayed that order last month.

State lawmakers also passed two laws this year strengthening and updating the state’s “builder’s remedy” which allows developers to flout city zoning rules to build affordable housing if a city hasn’t created a state-approved plan to sufficiently increase its housing stock.

With Norwalk’s housing plan now out of compliance, the county or another developer could use the builder’s remedy to advance the hotel project or other housing for formerly homeless people, Elmendorf said.

The city, which Newsom’s office said received nearly $29 million in state housing and homelessness funds in 2019, could also see that tap turned off for the time being.

Rios said that while city council members had no plans to back off the moratorium, she hoped it had garnered enough attention that state and county leaders would sit down and discuss with her about the best solutions to homelessness in Norwalk. In particular, she hoped the state would consider adding housing at Metropolitan State Hospital, a state mental hospital in Norwalk that she said already has the security and wraparound services to make transitional housing a success.

Housing department officials said they planned to meet with the city and would reevaluate its case if council members repeal the ordinance, but did not rule out a lawsuit. Newsom spokesperson Tara Gallegos added, “The state is happy to meet with Norwalk to discuss how they can comply with state law — but we will not schedule a meeting to discuss how they can best violate it.”

Further northeast in West Covina, Mayor Brian Tabatabai said he wished Newsom would come knocking. Tabatabai had worked to bring homeless housing to a local motel in his city through the same county Pathway Home program that was shot down in Norwalk. East Los Angeles County, he said, generally lacks interim housing for the homeless.

But his colleagues on the city council opposed the project, citing a school district survey that showed parents were concerned about locating the housing near several schools. In interviews, some council members said they generally supported homeless housing but wanted a project that would house families rather than single people or require residents to be sober.

“I think (Newsom) needs to hold cities accountable and I’m hoping he holds West Covina accountable as well,” Tabatabai said. “There needs to be pressure. It was 115 degrees in West Covina the other day and to think, we’ve got folks out here and we could’ve had them inside.”

###

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

OBITUARY: Robert Troy Jaramillo, 1986-2024

LoCO Staff / Friday, Oct. 4, 2024 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Robert Troy Jaramillo

May

7, 1986 – Sept 26, 2024

Robert Troy Jaramillo was born May 7, 1986, in Albuquerque, New Mexico. He is our beloved son, brother, father, grandson, uncle and friend. It is with deepest sorrow that we announce Robert’s passing on September 26, 2024.

Robert was a hardworking long-haul mover. They called him the Tetris packer because he was so skilled at his work. Robert worked with a partner, his lifetime best friend, Craig Broadhead, who he was inseparable from. Robert made friends everywhere he went with everyone he met; he was impossible not to love. Anything you needed he would do without question, gave the shirt off his back to those in need many times over.

Robert looked at his children with unending love in his eyes. Spending time with his children, family and friends were his greatest joy. In his down time Robert loved hunting, fishing, camping, hiking, working out and, of course, food. As he would say “Rob Rob loves food.” Robert had sparkling blue eyes and a smile to light up the whole room that you couldn’t help but smile back at. Robert’s love for his mom, his children, and his siblings ran deep. Robert was a fierce protector of his whole family and was both loved and appreciated by those he cared for.

The Lord had other plans for Robert and must have a special assignment needing his strong muscles and warrior’s spirit. Robert is loved so much by all and will be missed eternally. Our hearts are forever broken, as we grieve him, remember “Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted.” Matthew 5:4

Our Robert Troy Jaramillo is survived by his father Ruben R Jaramillo, mother Diana Woodward, stepfather Eli Woodward, brothers Joshua Jaramillo & Christian Bailey, stepsister Lexie Swanson, his children Ruben J, Matthew T, & Shianna M Jaramillo, grandma Linda Blankenship, uncles Guy, Bill, & Joe, Aunt Kathy, cousins Krystopher, Mylynda, Bryce, Leslie, & Jake, nephew Wyatt, and Sherice & Ashley.

Robert freely gave so much love and was so loved in return. Thank you all for you support and care for our Robert Troy, Our Fallen Wolf.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Robert Troy Jaramillo’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

OBITUARY: Greg Eastham, 1955-2024

LoCO Staff / Friday, Oct. 4, 2024 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Most people of the Fortuna area have known my father, Greg Eastham. They know him as Greg. I just

know him as Dad.

My father had a huge heart, and was very sensitive to the needs of others and would give his last dollar, meal or clothes to help someone else in need. As he did live a hard life and lifestyle which made it challenging for him to form lasting relationships and connections.

My Dad was born in Miranda and lived there as a young boy with his parents and siblings until they moved to Fortuna, where he completed high school and got married shortly thereafter while working at Safeway.

He worked with other friends at Safeway and was well liked by coworkers and colleagues. He was well known as a prankster and always had a good sense of humor. He mostly lived in this community, and briefly moved with his daughter in Solano County, to obtain some family connections and have a new work opportunity. He was able to be a grandfather for two of his grandsons and lived comfortably with them until again relocating to Fortuna.

There were many years of in/out of different and sometimes difficult living situations where family needed to give him some time for his healing process, but would be nearby to help in times of need. He loved going to the beach, driving fast and going out Highway 36 to swim in the rivers. He sought out peace, solitude and connecting with others in the ways he knew how.

My dad was known as Gramps to my daughter and his grandsons, and they would have fun together when he needed help with grocery shopping, companionship or going to church together. As he’d had times of difficulty with addictions, our families’ hope for him had always been to give him love and support, while offering dignity and respect for his own life choices whether or not we agreed with him.

After many health crisis, in and out of rehabilitation, and without constant health needs met, he passed away September 15, 2024.

My dad taught me what unconditional love means — to make time for myself, to set healthy boundaries, and to hold space for my emotions. To respond to negativity with calmness. To appreciate the present moment. To not be easily swayed by others’ opinions, and to feel content with who you are and where you’re headed. He taught me to show up just for yourself and accept yourself as you are, to choose yourself. He taught me to not feel the need to prove yourself to anyone and to enjoy solitude without feeling lonely. Of course, these lessons weren’t learned easily, and they were through the trials and tribulations of challenging life struggles, traumas and experiences.

There’s currently no date for services. Once that decision is made an announcement will be made if that is what we feel is best. At this time our family asks for prayers of peace, in times of deep grief, for all to know how fragile life can be and to prioritize peace.

Dad, we are sending you light, to heal you, to hold you.

We are sending you light, to hold you in love. Blessings on to you.

Love, your family

❤️❤️❤️❤️

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Greg Eastham’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.