The CHP Would Like to Build New Headquarters on the Property Championed by People Opposing Downtown Housing Development, and There Was a Meeting About it Yesterday

Isabella Vanderheiden / Friday, July 21, 2023 @ 11:05 a.m. / News

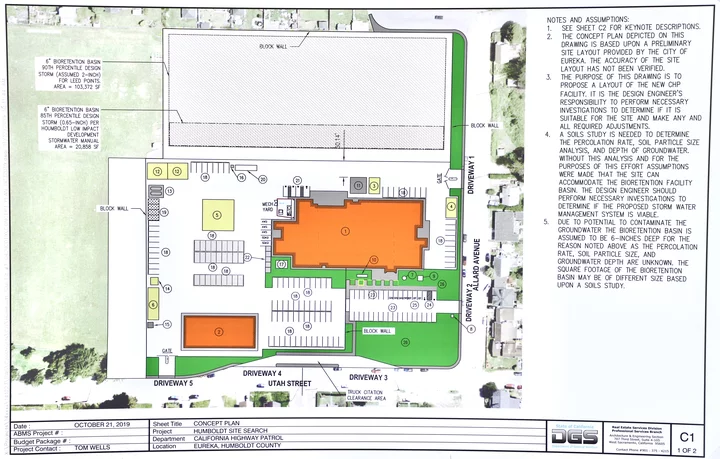

John Gambone, project director with California’s Department of General Services, presents plans for the CHP’s proposed facility. Photos by Andrew Goff.

###

For years, the California Highway Patrol has had its sights set on the former Jacobs Junior High School campus in Eureka’s Highland Park neighborhood as a potential location for its new headquarters. That vision is beginning to take shape.

Local CHP officials held an informational meeting at Fort Humboldt Historic State Park on Thursday afternoon to gauge community opinion about the proposal. There were around 20 attendees, including several representatives from the City of Eureka and a few community members, all of whom seemed to support the development.

“Honestly, I’ve lived here for 28 years, about a block away from that eyesore, and I can’t even imagine why anybody would not want this building,” said one resident of the Highland Park neighborhood, who chose not to identify herself. “It would blow my mind if somebody did not want this building because it’s just horrendous to look at right now. I support this 100 percent.”

The proposed facility would be positioned on the corner of Allard Avenue and Utah Street, in the footprint of the former school, with patrol traffic likely flowing west to Highway 101 via McCullens Avenue. Humboldt Area CHP Captain Commander Larry Depee, formerly of Del Norte County, compared the conceptual design of the building to the CHP headquarters that was built in Crescent City in 2019.

“I was part of the planning through groundbreaking and all the way through us moving in, so I have a pretty good idea about what happens with the new facilities from inception to the point where we’re actually using it as a functional facility,” Depee said. “We had some hiccups with it but we were able to overcome those. We listened to the public. We want to be a good neighbor. And all of the issues that we had, we were able to come up with some sort of resolution, some sort of compromise that worked, and we want to do the same here.”

CHP has been looking for a spot for a new facility since 2014, Depee said. The agency has looked at properties “all the way from McKinleyville, down south to Fortuna” but the former Jacobs Campus has proven to be one of the most promising sites, being somewhat centrally located in Eureka with easy access to the highway.

“Nothing has been set yet,” Depee continued. “We’ve decided on approximately how much property we need. … CHP has many facilities and they’re all about the same. The plans, they look the same with very minor differences.”

Sacramento-based CHP Lieutenant Brandon Baldwin added that all CHP facilities must be in compliance with the Emergency Services Act, which ensures that the building would “be able to withstand any type of major natural disasters.

“One of the biggest obstacles in Humboldt – aside from limited land availability in the area – is being outside of a tsunami zone,” Baldwin said. “That way if – heaven forbid – a tsunami does strike the area, the CHP facility would be out of the disaster zone. We they could still go out and provide assistance to this community without being affected adversely.”

New CHP facilities also include a “community room” to provide a gathering place for small meetings, Baldwin said. “As much as it is a home for us as a department, it’s also part of the community,” he said. “It really is the people’s house. So we want to be able to afford a portion of that area to be used for community purposes.”

There’s still a long road ahead. CHP is working with the Eureka City Unified School District to acquire the property, but the agency still needs to get approval from the state and the Department of Finance, Baldwin said.

The City of Eureka was in active property negotiations with the Eureka City Schools Board of Education up until last September when the school district declined “the city’s best and final offer” of $2.8 million for the entire 14.09-acre property – $1.2 million below the school district’s reported asking price of $4 million. The school district has not disclosed how much it is currently asking for the property, but it did confirm that CHP is the only entity involved in formal property negotiations.

“Eureka City Schools is still in active negotiations with the California Department of General Services (DGS), the entity representing CHP,” district spokesperson Sierra Speer Dillon wrote in an emailed response to the Outpost.

Thursday’s meeting seems to indicate that negotiations are getting a little more serious, but Dillon stated that “There has yet to be reportable action at this time.”

Similarly, John Gambone, project director with DGS’ Real Estate Services Division, emphasized several times throughout the meeting that DGS and CHP are in the beginning stages of negotiations with the school district.

Eureka City Councilmember Kati Moulton spoke in favor of the proposed development, noting that members of the South Eureka Neighborhood Alliance had asked nearby residents what they wanted to see happen at the former Jacobs campus “and CHP joining the neighborhood was really high on the list,” she said.

“I think it’d be welcomed,” Moulton continued. “Folks are concerned about what it’s going to look like [and] how it’s going to fit into the neighborhoods, so I’m really happy to hear you addressing that right off the bat. … I love the idea of you integrating into the neighborhood, being a bigger part of everything there and having folks feel like you’re a part of the neighborhood and not this sort of alien thing that just plopped down.”

Depee emphasized that CHP “definitely doesn’t want to be that large, anonymous agency that nobody can talk to.”

Moulton asked more about the community room Baldwin had mentioned and whether it would be a place that could offer shelter and relief during an emergency. “Sometimes folks will open up public buildings for charging a phone during a power outage or, you know, heating during extreme weather or something like that. Is that a resource that we could talk about and have access to?”

During his time in Crescent City, Depee said CHP would work with the California Office of Emergency Services (CalOES) to offer services in their community room. “My assumption is that we will do the same thing here,” he said. “We will do everything that we can to work with all of our allied agencies and to work with the community to offer up as much as we can with this facility.”

Moulton also asked if the public would have a chance to weigh in on the appearance of the building, given that “people are going to live across the street from this thing presumably for decades.”

Baldwin said CHP would be willing to work with the community on superficial aspects of the building’s design, like the color of its roof, but said there would be other, more technical aspects that would be out of their control.

“For example, there would be a radio tower on top of the building,” he said, noting that the tower would be approximately 140 feet tall. “It’s really up to CalOES where that tower will be located because they’ll have to bring out a large lift and see what would be the best radio connectivity to the radio towers around here. That will dictate where the tower goes on the property.”

The Outpost asked Depee how patrol traffic from the facility would impact the surrounding neighborhood. Depee said Crescent City’s new headquarters was built in a business district and the agency worked with community members to develop a local standard operating procedure (SOP).

“So we said we would not turn on the siren, we wouldn’t be responding fast, until we got to U.S. 101. This would be something very similar,” he said. “Now, obviously, there will be calls that are gonna necessitate us traveling a little bit faster, but we’ll have that SOP in place. Our supervisors and myself are ultimately responsible for it and we will manage that and ensure that our troops are driving safely through these areas. … We’ll do everything we can to mitigate or eliminate any impacts to traffic if it’s not necessary.”

Depee added that CHP would work with the Eureka Police Department to address criminal activity in the neighborhood.

“Our agencies work very well together,” he said. “If there was a call for service, we would immediately respond. We don’t even generally wait for a request. If we’re the closest unit, we’re going to respond.”

We also asked what would happen to CHP’s existing facility on Samoa Boulevard in Arcata. Depee said Caltrans took over CHP’s old facility in Crescent City and said, “That’s probably something that we would look into.”

If the deal moves forward, it would throw a big wrench in the gears for a group of Eureka residents that want to see the site turned into housing.

Just last week, two Eureka residents – Michelle Costantine-Blackwell and Michael Munson – filed a “notice of intent” to circulate a petition to put an initiative on the ballot that would require the City of Eureka to amend its General Plan to rezone the Jacobs site for housing in an attempt to stop the city from building housing on underutilized downtown parking lots.

It’s unclear whether rezoning the Jacobs Campus for housing would actually result in a new housing development on the site. As previously stated, the City of Eureka has expressed interest in building market-rate housing on the site, but it seems CHP is now the main contender.

Negotiations are still ongoing.

Looking down McCullens Avenue to Highway 101 from the Jacobs site. Images depicting the current state of the site below.

Previously:

- As Pressure From Neighbors Mounts, Eureka School Board Poised to Decide What to Do With Abandoned Jacobs Campus

- Eureka School Board Votes to Sell Abandoned Jacobs Campus; California Highway Patrol Has Expressed Interest in the Property

- Who Will Get the Former Jacobs Campus? Bidders for Blighted Site in Highland Park Are the City of Eureka and the California Highway Patrol, With a Decision Coming Soon

BOOKED

Today: 12 felonies, 18 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Yesterday

CHP REPORTS

Dundas Rd / Parkway Dr (HM office): Trfc Collision-1141 Enrt

Beach Rd / Humboldt Loop (HM office): Trfc Collision-No Inj

ELSEWHERE

Times-Standard : Civic calendar | Coastal commission to discuss Eureka’s proposed Marina Center

RHBB: Local Group Steps Up as Feds Step Down on Disaster Response

RHBB: Humboldt County Loses Another Aviation Director — Third in 18 Months

Some of California’s ‘Cheapest’ Cities Have Seen the Biggest Rent Hikes

Ben Christopher / Friday, July 21, 2023 @ 8:49 a.m. / Sacramento

A home with a real estate sign in Tower District in central Fresno on June 28, 2022. Photo by Larry Valenzuela, CalMatters/CatchLight Local

Inland cities including Bakersfield, Fresno, Visalia and Riverside — once cheaper options than pricey places such as the Bay Area — are no longer refuges from California’s housing affordability crisis.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, the typical asking rent in these former bastions of relative affordability have exploded by as much as 40%, according to data from the real-estate listings company Zillow.

California’s inland rent spike is yet another lasting effect of the COVID-19 pandemic. Beginning in 2020, California’s dense metropolitan coast saw an outflux of people, as educated white-collar workers, suddenly untethered from the office, packed their bags in search of cheaper and more socially distanced modes of living.

For many smaller California towns, the surge of new residents competing for housing has placed new financial pressures on lower-income residents, upended local housing markets and, in some cases, shifted the politics around housing and affordability.

In Santa Maria, just an hour up the 101 from Santa Barbara, the last three years have been a “perfect storm” for renters, said Victor Honma, who oversees housing vouchers across the region for the Housing Authority of the County of Santa Barbara.

The town was awash in suburb-seeking homebuyers from Los Angeles, the Bay Area and nearby Santa Barbara and San Luis Obispo. The suddenly hot housing market persuaded many longtime local property owners to sell their rentals to the wave of new homebuyers, reducing the rental stock further. And though Santa Maria had always had a “healthy supply of inventory,” said Honma, the available homes ran on the large side, leaving few one-bedroom units to go around for many suddenly desperate renters.

These trends were in the works prior to 2020, but “the pandemic was a stimulus,” he said.

It’s the same story in Bakersfield, where rents have jumped 39% since March 2020, as priced out Angelenos migrated north of the Grapevine, said Stephen Pelz, executive director of the housing authority in Kern County.

Since then rising interest rates have cooled the national housing market. But Pelz said the higher cost of borrowing has only added to the woes of Kern County renters: Fewer people purchasing homes has meant more competition for the area’s remaining rental units.

An inevitable consequence

Jeff Tucker, an economist at Zillow, said the inland rental crunch is the inexorable result of California’s overall housing shortage, as the affordability crisis along the coast ripples outward. Cities in the Central Valley used to enjoy a healthy “affordability advantage” over coastal urban areas, he said. But that advantage has begun to shrink over the last three years.

“People have been moving towards that more affordable option when they don’t have anywhere else in California that they can afford,” said Tucker.

According to Zillow’s seasonally adjusted “observed rent index” — a kind of gussied-up average that strips out exceptionally pricey or cheap outliers in a given market — the typical rent in the Fresno metropolitan used to be 54% cheaper than that in San Francisco. As of June 2023, that discount dropped to 40%.

“People have been moving towards that more affordable option when they don’t have anywhere else in California that they can afford.”

— Jeff Tucker, economist at Zillow

Further south in Bakersfield, where renters used to pay roughly half of L.A. area tenants, on average, the difference has narrowed to 40%.

In part, that’s just a function of arithmetic. In both the Bakersfield and the Los Angeles metro areas, the typical rent increased by a little more than $500 since the beginning of the pandemic. Because Kern County rents were much lower to begin with, $500 represents a larger percentage hike.

But for the average Bakersfield area resident, that $500 rent hike pinches a lot harder: The average income in Kern County is roughly $25,000, according to the most recent Census data. In L.A. County, the average is $38,000.

Some modest relief could be on the way.

The cities of Bakersfield, Visalia and Fresno have all permitted roughly 15% more units in 2021 and 2022 than they did in the two years before the pandemic, according to data collected by the state Housing and Community Development Department.

The city of Santa Maria has permitted 150% more. The bulk of the new or incoming units around town are accessory dwelling units — backyard cottages and annexes. For a city short on lower-cost single bedroom places to live, the new crop of ADUs are “really filling that gap,” said Honma.

Pro-renter advocates unsuccessful

While building more places for people to live is one part of the battle, others have tried to soften the impact on rents of existing housing stock.

Earlier this year, tenant rights and anti-poverty advocates mounted a campaign to push the city of Fresno to adopt a rent control ordinance. For a city whose most notable politico, Democratic U.S. Rep. Jim Costa, lent his name to a state law that restricts local governments for enacting or expanding rent control laws, it was a symbolic push.

Further south, activists in Delano were competing to see which town would be the first in the Central Valley to enact a permanent cap on rent hikes.

Neither campaign was successful. Fresno’s city council declined to include a rent stabilization program in its budget for this fiscal year and elected leaders in Delano agreed only to study the issue.

In Sacramento, many of these same advocacy organizations have been pushing a bill by state Sen. María Elena Durazo that would have, among other things, lowered a statewide cap on annual rent increases from 10% to a mere 5%. But that provision was stripped out, leaving only new rules that make it harder for landlords to evict tenants without cause.

###

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

OBITUARY: Caroline Diane Brooks Chaffin, 1976-2023

LoCO Staff / Friday, July 21, 2023 @ 8:20 a.m. / Obits

In Loving Memory

Caroline Diane Brooks Chaffin

May 23, 1976 - July 5, 2023

It is with deep sorrow and much love that we mourn the passing of Caroline Diane Brooks Chaffin. Born on May 23, 1976, at Balboa Naval Hospital, San Diego, she was called to her heavenly abode on July 5, 2023. Caroline was a vibrant, caring, and jovial woman whose compassionate and humble spirit illumined the lives of many. Her mantra in life was to be respectful, be kind, and to always say thank you. There’s no denying that she made a profound impact on those who were blessed to know her.

Caroline is survived by her loving mother, Kim Trevillion, her loving father, Roy G. Brooks, Jr., and her devoted husband, John William Chaffin. She also leaves behind her aunts, Darlene and Debra, uncle Michael Brooks and her cousin, Kathy Greene and other family members. Caroline was predeceased by her beloved grandmothers, Yoshiko M. Brooks and Nettie White, her grandfathers, Roy Brooks, Sr. and Donnie Joe White, uncles Thomas P. Brooks and Faye W. Moore. She had many friends.

A canny businesswoman and a go-getter, Caroline was proud of her successful small business, Caroline’s TX BBQ. She was not only an independent and phenomenal woman but also a loving guardian to her husband’s niece and nephew, whom she raised with all the love and care in the world.

Caroline was an active member of The Ingomar Club, a local and private club where she made countless fond memories. Her love for life reflected in her diverse range of interests, from her favorite foods, BLTs, brisket burgers, Chicken Makhani, Biryani, enchiladas, tamales, and gyros to her preferred drinks, particularly Country Time Lemonade, Pineapple and Big Red sodas. She was an avid reader and fan of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, To Kill A Mockingbird, and she found joy in the music of Prince, Chicago, Bell Biv DeVoe, Miles Davis, and Joe Bonamassa.

She was an ardent supporter of Golden State Warriors and enjoyed playing games like Greed, Monopoly, Scribble, Jinga, and Quarter Craze Bingo. Her favorite performances to watch included The Nutcracker. Caroline loved to keep active through walking, aerobics, swimming, and bike riding. Her most cherished local spot was Gabriel’s, and she always looked forward to trips to Paris, France, Belfast, Ireland, the UK, Ohio, Texas, and San Diego. The last journey she made was on a Catholic pilgrimage to Portugal, Fátima, Lourdes and Barcelona with her mother.

Caroline was a lover of art, with a particular affection for the surrealistic works of Salvador Dali. Her favorite movies, Airplane, Tombstone, Open Range, Shaft, Dial M for Murder, and crime TV shows kept her entertained during her downtime. Her vibrant personality was further accentuated by her favorite color, yellow. Passionate about animal welfare, Caroline was a staunch supporter of the ASPCA.

In passing, Caroline leaves behind a legacy of kindness and compassion. She will be profoundly missed by all who knew her. As we grieve her loss, we also celebrate her remarkable life, ever inspired by her unwavering spirit and enduring teachings.

Celebration of Life will be on August 19, 2023 at the Ingomar Club, Eureka.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Caroline Chaffin’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

A Residential and Commercial Development is Proposed for the Vacant Lot Next to Arcata’s Greenview Market, and at Least One Person is Not Very Happy About it

Stephanie McGeary / Thursday, July 20, 2023 @ 3:36 p.m. / Housing , Local Government

The lot next to Greenview Market | Photos: Stephanie McGeary

###

The long-vacant lot at 11th Street and Janes Road, next to Greenview Market in Arcata, may soon be developed into a housing and business complex. Local development company North Star Development LLC has filed for a design review permit that will be considered by the Arcata Planning Commission next week.

According to the plans filed with the City, the project would include the construction of three two-story buildings – two residential buildings that would hold a combined total of 22 two-bedroom units, and a third building that would hold two commercial spaces. The site plans also include the addition of a parking lot with 23 vehicle spaces and 18 bike parking spaces, plus some landscaping additions.

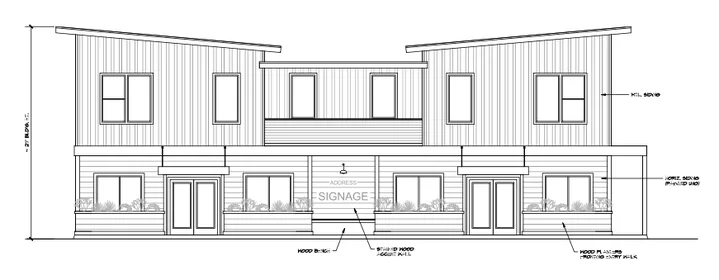

Above: Design for the commercial building that would face 11th Street. Below: Design for the larger of the residential buildings | Images from plans submitted to the City of Arcata

A reader informed the Outpost that the proposed project already has some pushback from people (or at least one person) in the community and that someone has posted fliers near the lot calling for residents to “save the neighborhood” by either attending the Planning Commission meeting or writing to city staff to oppose the new development.

“Northstar development wants to build a complex next to Greenview Market that will completely change and ruin the character of this neighborhood,” a laminated flier pinned to the utility poles in front of Greenview Market reads. “Stop the greed of exploitative development! Let the city know that this development is wrong for this neighborhood!”

Because the property is already zoned for mixed-use development and it is not in the coastal zone, the approval process is pretty straightforward. David Loya, director of community development for the City of Arcata, told the Outpost that if the Planning Commission approves the permit, the development will be able to move forward and will require no further review from the City. The only exception is if someone files an appeal with the city council. Appeals must be filed within 10 business days of the Planning Commission’s action.

The Arcata Planning Commission will conduct a public hearing on the proposed project during its regular meeting on Tuesday, July 25 at 5:30 p.m. at Arcata City Hall – 736 F Street. You can view the notice here and view the full design plans here. The full agenda has not yet been posted, but will most likely be posted by Friday. When posted, you will be able to view the full agenda and directions on how to participate in the meeting here.

You can also email your comments or questions to Delo Freitas, senior planner, before the meeting at dfrietas@cityofarcata.org.

Two Arrested On Illegal Firearms Charges After Drug Task Force Agents Serve Warrants at Suspect’s Home, Storage Unit

LoCO Staff / Thursday, July 20, 2023 @ 1:14 p.m. / Crime

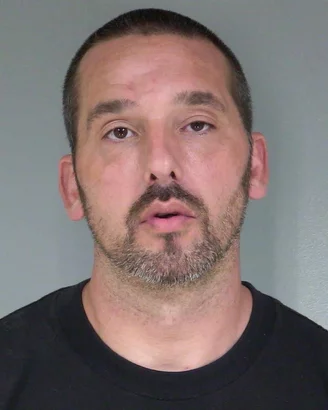

Photos: HCDTF.

Press release from the Humboldt County Drug Task Force:

On July 19th, 2023, Humboldt County Drug Task Force Agents, with assistance from the Eureka Police Department and the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office, served a search warrant at the residence of Justin Lee ZWIEFELHOFER (age 40) located in the 2900 block of Mack Road in Arcata. The Humboldt County Drug Task Force received information that ZWIEFELHOFER was trafficking narcotics and firearms throughout Humboldt County.

Upon arrival at ZWIEFELHOFER’s residence, Agents located and detained ZWIEFELHOFER and Chloe WELLS (age 22) without incident. Once the scene was secure, Agents searched the residence and located two firearms, a useable amount of cocaine, scales, packaging materials and indicia of drug sales.

ZWIEFELHOFER advised Agents that he possessed a storage unit in McKinleyville which also contained firearms. Humboldt County Drug Task Force Agents obtained a second search warrant for the storage unit and located seven firearms including an assault weapon, a high capacity magazine and a short barreled rifle.

Justin ZWIEFELHOFER was transported to the Humboldt County Correctional Facility where he was booked on the following charges:

HS11370.1(A)- Possession of a controlled substance while armed

PC32310- Possession of a high-capacity magazine

PC30605(A)- Possession of an assault weapon

PC33215- Possession of a short-barreled rifle

Chloe WELLS was transported to the Humboldt County Correctional Facility where she was booked for HS11370.1(A)- Possession of a controlled substance while armed.

Anyone with information related to this investigation or other narcotics related crimes is encouraged to call the Humboldt County Drug Task Force at 707-267-9976.

Here’s How California’s Electric Cars Can Feed the Grid and Help Avoid Brownouts

Alejandro Lazo / Thursday, July 20, 2023 @ 7:39 a.m. / Sacramento

Electric school bus at the Cajon Valley Union School District in El Cajon were used to help feed power into the grid during last summer’s heat wave. Photo via the California Energy Commission

As a historic 10-day heat wave threatened brownouts across California last summer, a small San Diego County school district did its part to help: It captured excess power from its electric school buses and sent it back to the state’s overwhelmed grid.

The eight school buses provided enough power for 452 homes each day of the heat wave, and the buses were recharged only during off hours when the grid was not strained.

California energy officials have high hopes that this new power source, called bidirectional charging, will boost California’s power supply as it ramps up its ambitious agenda of electrifying its cars, trucks and buses while switching to 100% clean energy.

Gov. Gavin Newsom called two-way charging technology a “game changer,” saying “this is the future” during a speech last September, about a week after the heat wave ended.

This year, a bill already approved by the state Senate in a 29-9 vote would require all new electric cars sold in California to be equipped with bidirectional technology by 2030. In the Assembly, two committees approved the bill earlier this month and it is now under consideration by a third.

This two-way charging has big potential — but also faces big obstacles. By 2035, California expects to have 12.5 million electric cars on the road, but it’s an open question how much California can rely on them to feed the grid. Automakers say the technology would add thousands of dollars to the cost of an electric car, and California’s utilities are still sorting out how to pay ratepayers for selling them the kilowatt hours.

The ability to use electric cars, trucks and buses to feed energy back into the grid would be especially helpful during peak times for energy use, such as heatwaves. But relying on vehicles as a year-round power source may not be practical — at least not yet.

“It’s a great idea conceptually…but we haven’t had the time to flesh out the details of what needs to happen for California to be able to power itself on electric vehicles,” said Orville Thomas, state policy director for CALSTART, a sustainable energy nonprofit.

“It should be on the menu of options that California has. Is it going to be the number one option? Definitely not.”

“It’s a great idea conceptually…but we haven’t had the time to flesh out the details of what needs to happen for California to be able to power itself on electric vehicles.”

— Orville Thomas, CALSTART

So far, its use has been limited in California. Pacific Gas and Electric has a pilot program — the first in the nation — that lets up to 1,000 residential customers with bidirectional chargers sell power back to the utility. Some school districts also are experimenting with it.

Only about half a dozen electric car models currently are equipped with bidirectional capabilities, including the Hyundai Ioniq 5, Nissan Leaf and Ford F-150 Lightning. Tesla announced recently that all its models will have it by 2025.

Electric vehicles convert one type of energy, alternating current electricity, into another, direct current, which is stored in a battery. Bidirectional charging means that an electric vehicle can convert the energy it has stored in its battery and send it to other sources, such as home appliances or back to the grid.

Willett M. Kempton, a University of Delaware professor who has studied bidirectional charging for more than two decades, said the vast majority of the time a vehicle is parked and not using electricity.

“Five percent of the time you’re using the car and you want to have enough energy — electricity or gasoline — to get to where you’re going and back. But most of the time, it’s just sitting there and some other use could be made of it,” he said.

Kempton said these vehicles, properly managed, could be sources of reserve energy, supplanting backup sources that burn fossil fuels.

Gregory Poilasne, co-founder and CEO of Nuvve Holding Corp., which sells electric fleet charging services, said a big challenge is that cars are unreliable energy assets. “At any time, somebody might come in and unplug the car,” he said. But he added, as the technology becomes more reliable and affordable, bidirectional cars and fleets should increase.

The cost: $3,700 per car

In Denmark, bidirectional charging earns electric vehicle fleet owners who sell power to the grid $3,000 per vehicle a year, Poilasne said, adding that this reduces the average total cost of electric car ownership by about 40%.

But citing the high cost, automakers oppose the Senate bill that would mandate the chargers for all new cars sold in California by 2030. It would increase the average cost of an electric car by $3,700, according to an opposition letter written by Curt Augustine of the Alliance for Automotive Innovation, which represents General Motors, Ford and other major auto companies.

“Not all customers will see an advantage of bidirectional charging, and therefore, should not have to pay more for a technology that they will not use.”

— Curt Augustine, Alliance for Automotive Innovation

About $3,000 of that cost would be adding battery capacity to meet warranty requirements, while other costs are for hardware and software.

“This technology is a competitive matter between vehicle manufacturers and should remain that way,” Augustine wrote. “Not all customers will see an advantage of bidirectional charging, and therefore, should not have to pay more for a technology that they will not use.”

Thomas of CALSTART agreed, saying it should be optional.

“There might be a situation where there are people that want to do it and will pay a little extra for a car that is bidirectional, but there will also be people that just want to use a vehicle for driving,” he said. “Do we raise the price of electric vehicles for everybody?”

But Sen. Nancy Skinner, a Democrat from Oakland who authored SB 233, said she wants to ensure that automakers don’t reserve the technology for only their higher-end models. She said since the relatively affordable Nissan Leaf has it, it can be widely available.

Skinner said all consumers would benefit from the technology by selling energy to the grid or using the energy in emergencies. But she said another important reason is that it could end reliance on diesel generators during power emergencies like during wildfires.

“If you have an EV you don’t need that diesel generator,” Skinner said. “Why would we want to encourage diesel generators? They’re extremely polluting.”Jeffrey Lu, an air pollution specialist with the California Energy Commission’s vehicle-grid integration unit, said the state is working with owners to identify the best times to charge — called smart charging — to protect the grid. Bidirectional charging takes the concept a step further, he said.

The Energy Commission is not yet ready to say how reliant California will be on bidirectional charging to provide sufficient power and meet the state’s 2045 mandate for carbon-free electricity.

“We’re fairly early in this process. California is very committed to load flexibility broadly, but where that load flexibility specifically comes from, how many megawatts or gigawatts are coming from any particular kind of resource? We’re working on that,” he said.

California’s utilities are running pilot projects and studying how bidirectional charging might work and how electric car owners could be compensated for selling energy to the grid.

“By selling it back to the grid when our rates are more expensive, then that actually helps reduce customers’ energy bills.”

— Chanel Parson, Southern California Edison

The California Public Utilities Commission has studied the issue for more than a decade, said spokesperson Terrie D. Prosper, including funding pilot projects and establishing two working groups.

Last year many utilities signed a “Vehicle to Everything” memorandum of understanding with car manufacturers, state agencies, the federal government and others seeking to accelerate all aspects of bidirectional charging.

Southern California Edison, which serves about 5 million businesses and residences, wants to go beyond using bidirectional charging as just an emergency backup.

Chanel Parson, Edison’s director of electrification, said the utility is working on a rate program that would allow customers to sell their power back to the grid every day of the year.

“By selling it back to the grid when our rates are more expensive, then that actually helps reduce customers’ energy bills. And it could be so economically attractive that they’re actually making money,” she said.

“Five years is definitely within reach. Technology is advancing quite fast.”

— José María Paz, Pacific Gas and Electric

Pacific Gas and Electric, which serves 5.5 million electric customers in Northern California, said it is aggressively looking to build what it calls a robust vehicle-to-grid-integration. It has partnerships with BMW of North America, Ford Motor Company and General Motors exploring bidirectional charging.

The utility last year launched the nation’s first bidirectional charging pilot available to residential customers, offering up to 1,000 customers $2,500 for enrolling and up to an additional $2,175, depending on their participation.

The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power also is conducting a pilot project using a small fleet of its Nissan Leafs. The utility hopes the technology will eventually provide power during peak load times.

“Five years is definitely within reach,” said José María Paz, the utility’s project manager for vehicle-to-grid integration. “Technology is advancing quite fast.”

School buses are a test case

The electric school buses at the Cajon Valley Union School District in San Diego County are among a number of school district pilot projects in California. Experts see school buses as a good option for two-way charging because they have set routes and are often parked during peak load times between 4 p.m. and 9 p.m.

Nationally, Nuvve has about 350 school buses connected to its platform.

At the Cajon Valley district, eight electric buses sent 767 kilowatt hours of power back to the grid during the heat wave between Aug. 17 and Sept. 9, according to Nuvve.

Working with Nuvve, the buses power up when energy is less expensive, said Tysen Brodwolf, the district’s transportation director. Brodwolf said there are still several quirks, including the chargers not communicating properly with the grid or someone improperly plugging in a bus.

“But we’re getting there every day,” Brodwolf said. “We’re working through all those bumps and obviously, when you take on a pilot project, you have to take that into consideration that things aren’t necessarily going to go smoothly.”

###

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

Are Major Changes Coming to Your Electric Bill? 5 Things to Know

Wendy Fry / Thursday, July 20, 2023 @ 7:33 a.m. / Sacramento

The sun sets behind a row of electric towers in Fresno County on Sept. 6, 2022. Photo by Larry Valenzuela, CalMatters/CatchLight Local

###

California’s electric bills — already some of the highest in the nation — are rising, but regulators are debating a new plan to charge customers based on their income level.

Typically what you pay for electricity depends on how much you use. But the state’s three largest electric utilities — Southern California Edison Company, Pacific Gas and Electric Company and San Diego Gas & Electric Company — have proposed a plan to charge customers not just for how much energy they use, but also based on their household income. Their proposal is one of several state regulators received designed to accommodate a new law to make energy less costly for California’s lowest-income customers.

Some state Republican lawmakers are warning the changes could produce unintended results, such as weakening incentives to conserve electricity or raising costs for customers using solar energy.

But the utility companies say the measure would reduce electricity bills for the lowest income customers. Those residents would save about $300 per year, utilities estimate.

California households earning more than $180,000 a year would end up paying an average of $500 more a year on their electricity bills, according to the proposal from utility companies.

The California Public Utilities Commission’s deadline for deciding on the suggested changes is July 1, 2024. The proposals come at a time when many moderate and low-income families are being priced out of California by rising housing costs.

Who wants to change the fee structure?

Lawmakers passed and Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a comprehensive energy bill last summer that mandates restructuring electricity pricing.

The Legislature passed the measure in a “trailer-bill” process that limited deliberation. Included in the 21,000-word law are a few sentences requiring the public utilities commission to establish a “fixed monthly fee” based on each customer’s household income.

A similar idea was first proposed in 2021 by researchers at UC Berkeley and the nonprofit thinktank Next 10. Their main recommendation was to split utility costs into two buckets. Fixed charges, which everyone has to pay just to be connected to the energy grid, would be based on income levels. Variable charges would depend on how much electricity you use.

“It will shift the burden, on average, to a more progressive system that recovers more from higher income households and less from lower income households.”

— James Sallee, associate professor at UC Berkeley

Utilities say that part of customers’ bills still will be based on usage, but the other portion will reduce costs for lower- and middle-income customers, who “pay a greater percentage of their income towards their electricity bill relative to higher income customers,” the utilities argued in a recent filing.

They said the current billing system is unjust, regressive and fails to recognize differences in energy usage among households,

“When we were putting together the reform proposal, front and center in our mind were customers who live paycheck to paycheck, who struggle to pay for essentials such as energy, housing and food,” Caroline Winn, CEO of San Diego Gas & Electric in a statement.

The utilities say in their proposal that the changes likely would not reduce or increase their revenues.

James Sallee, an associate professor at UC Berkeley, said the utilities’ prior system of billing customers mostly by measuring their electric use to pay for what are essentially fixed costs for power is inefficient and regressive.

The proposed changes are designed to be more progressive, he said.

“It will shift the burden, on average, to a more progressive system that recovers more from higher income households and less from lower income households,” he said.

What would the proposed fixed-charge fees pay for?

Revenues from the fixed charges would help cover utilities’ costs to provide customer service, including meters, poles, wildfire preparedness, operations and maintenance, according to the Public Utilities Commission, which regulates private utilities.

The fixed charge would not be the only portion of a customer’s bill. Customers would still be able to lower the portion of their energy bills that is based on usage by doing such things as investing in solar panels or strategically running appliances during non-peak times.

Why is this proposal controversial?

Supporters say it will help lower costs for low-income customers, who spend higher proportions of their income on electricity than other customers.

Critics of the proposed plan say it is unfair to those who have been trying to conserve energy.

Some state Senate Republicans say the proposed utility billing changes would make living in California less affordable and could discourage energy conservation. If energy bills are based on someone’s income and not on how much electricity they use, customers would little incentive to turn off the air conditioner during peak hours, they argue.

I would hate to think about people who are not using their air conditioning or fans during the summer because they can’t afford it. That’s no way to live.”

— Leah Jacobson, sociology grad student at UCLA

Del Mar resident Rosanna Alvarado Martin said she and her husband are both budget and environmentally conscious, so they recently signed contracts to install solar panels on both their Del Mar and University City residential properties.

Now Martin worries her electricity bills will go up no matter how much energy she saves with solar.

“This was really a kick in the gut. The whole thing is just really frustrating,” she said. “We’re looking to retire soon. So we’re looking to have some control over what our expenses are going to be in retirement, and this solar, to me, was one way we could do that.”

On the other hand, Leah Jacobson, a sociology grad student at UCLA, said she’s in favor of the proposed changes because they might bring stability to her monthly bills. A few times her bill has shot up to more than $400 a month, she said.

“There have been a couple times in the last year where our bill has jumped up a couple hundred dollars and we haven’t been able to figure out why,” Jacobson said.

“Thankfully, we were in a position where the amount is usually affordable when it doesn’t jump up like that. But I would hate to think about people who are not using their air conditioning or fans during the summer because they can’t afford it. That’s no way to live.”

Another major issue: data collection. To implement the changes, the state will have to categorize approximately 14 million households into income brackets, and a third-party administrator probably will have to verify their incomes, state and utilities officials say.

Because California’s Employment Development Department and the state’s long-time debit card contractor Bank of America have been plagued by cases of fraud, some critics worry the state won’t be able to keep people’s financial information confidential.

“The proposed fixed charges, without clarity on how Californians’ income will be verified, are not only questionable but also raise concerns about data privacy,” Senate Minority Leader Brian Jones, a Republican from El Cajon, told CalMatters. The utilities “are not set up to do income verification, nor should they be, as this is a major privacy concern.”

So far Democrats, who passed the bill with the fee-structure changes, have not spoken in a unified way about the proposed changes.

Why are California energy rates so high in the first place?

California’s average retail electricity price is nearly double the national average.

While the state has been at the tip of the spear of the green energy movement with early adoption of wind and solar, it lags behind other states in replacing aging and failing power lines, according to a 2022 audit report to the California Legislature.

And because the state is so spread out geographically, it costs more to build and connect its infrastructure for energy generation, maintenance, distribution and wildfire mitigation. Those costs don’t vary by how much electricity customers use, but they are driven up by climate change as California becomes hotter and drier.

Nevertheless, all three utility companies showed gross profit gains last year. PG&E reported a 3% bump to $16.8 billion in gross profits, which subtract the costs of production from revenues. Similarly, Edison’s $10.9 billion in gross profits was 15% better than the prior year, and SDG&E parent Sempra’s profit, at $9.9 billion, was a 3% improvement. Once all other expenses are accounted for, including such things as lawsuits, depreciation and taxes, both PG&E’s and Edison’s net incomes shrank for 2021.

As more Californians replace their gas-powered vehicles with electric ones, consumption of electricity is expected to increase. Under new state regulations, 35% of new 2026 car models must be zero-emissions, ramping up to 100% in 2035. State officials say the 12.5 million electric vehicles expected on California’s roads in 2035 will not strain the grid.

Are there other proposals?

Among several alternatives, one comes from the Utility Reform Network (TURN), a nonprofit consumer advocacy organization headquartered in San Francisco.

Its proposal filed with the regulatory agency also calls for an income-based fixed charge, but its proposed fixed fees are much lower than what the utilities want.

The group says the utilities already profit enough from customer fees.

“The (utility commission) has to work out all those details and the devil is in the details,” said TURN’s Executive Director Mark Toney.

The public will have a chance to weigh-in on the proposals by submitting comments online or attending a commission meeting.

Though the state set a 2024 deadline for the commission to establish fixed monthly fees based on customers’ incomes, an administrative judge in the proceedings wrote in a recent filing that the earliest the change could be implemented is the end of 2026.

How much would customers pay?

In the power companies’ joint submission to the California Public Utilities Commission, they suggest these fixed fees for each customer’s income range.

- Households with incomes earning less than $28,000 a year would pay a $15 monthly fee in the Edison and PG&E service territories and a $24 monthly fee in SDG&E service territory.

- Households earning $28,000 to $69,000 a year would pay $20 to Edison, $30 to PG&E or $34 to SDG&E each month.

- Households earning $69,000 to $180,000 would pay $51 to Edison or PG&E, or $73 to SDG&E.

- Households earning more than $180,000 would pay $85 to Edison, $92 to PG&E or $128 to SDG&E.

###

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.