NEXT UP in the GATEWAY AREA PLAN: Arcata Planning Commission to Review Draft of the City’s New Form-Based Code that Will Guide New Development in the Gateway

Stephanie McGeary / Tuesday, June 13, 2023 @ 1:09 p.m. / Local Government

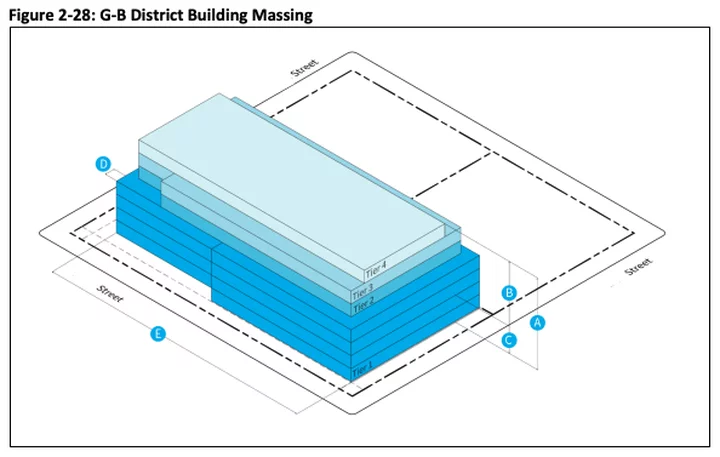

Image showing what a building’s size and setbacks might look like in the Gateway’s ‘Barrel District’ | Image from Arcata’s draft form-based code

###

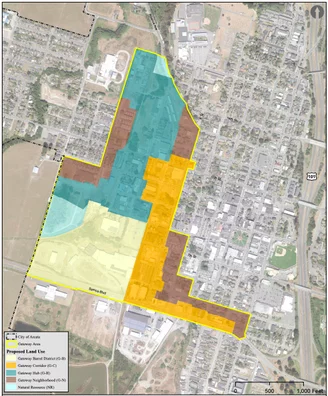

The Arcata Planning Commission will, once again, discuss the controversial Gateway Area Plan – a section of the city’s General Plan that will rezone 138 acres of land near downtown to facilitate the creation of high-density housing – on Tuesday evening, as it gears up to make a recommendation on the plan to the Arcata City Council next month.

The main focus of Tuesday’s meeting will be reviewing the draft of the form-based code, which was put out last week. The 58-page draft code (which you can view here) lays out the requirements and processes that the City will use to approve new development in Arcata’s Gateway area, including building design requirements — for example, how far the building must be set back from the street, how building facades should be constructed and what materials can be used.

Depending on a proposed development’s size and which section of the Gateway Area it is in (the Gateway has been divided into four areas: the Barrel District, the Gateway Hub, the Gateway Corridor and Gateway Neighborhood), the permitting process will look slightly different. But the idea is that if developers meet all of the requirements outlined in the code, the approval process will be streamlined, so that a full review process is not necessary for all new developments.

Since one of the most controversial aspects of this plan has been building height, it also seems important to point out that the building maximum building heights are set in the code, with up to four stories being permitted in the Gateway Neighborhood, up to five stories in the Gateway Corridor, six stories in the Gateway Hub and seven stories in the Barrel District. Depending on the footprint and height of the building, there will be a different permitting process. Projects that are less than 30,000 square feet and/or have a building height of 37 feet or less, will only need approval from the City’s Zoning Administrator, whereas buildings that are more than 40,000 square feet and more than 40 feet high, will go through the Planning Commission.

The code also outlines different permitted uses for new developments in the Gateway Area, including multi-family housing, rooming or boarding houses, residential care facilities, and existing single-family dwellings; commercial uses, including retail, personal services, restaurants and bars, professional offices, medical services, and lodging; and recreation, education, and public assembly uses, including parks, playgrounds, schools, meeting facilities, studios, and theaters. Some uses that are prohibited for new developments include new single-family dwellings, heavy industrial uses, construction yards, service stations, warehouses, personal storage (mini-storage) facilities, fuel dealers and auto sales and rental business.

One of the concerns that community members have brought up in various past meetings is how the new zoning will affect the existing businesses in the Gateway Area. David Loya, community development director for the City of Arcata, told the Outpost that existing businesses that fall under one of these uses are allowed under the code as “existing non-conforming” uses. Though the City is interested in helping businesses relocate to more suitable areas, if they so wish, no one will be required to move out, as some people have claimed.

“I feel like there’s a really unfounded fear about this,” Loya said in a phone interview Tuesday morning. “All existing non-conforming uses will still be able to operate … and we’re explicitly allowing existing non-conforming businesses to expand.”

The code also outlines where demolition of existing buildings is permitted, which includes a segment of the property near the Creamery Building between N and L Streets and 8th and 9th streets. Aside from those buildings, any other demolition, modification or relocation of existing buildings would require review from the Planning Commission.

The one section of the Gateway where buildings can be demolished without an additional design review process

The form-based code is just one document that the Planning Commission is working on, and the commission has spent the last several months going over every element of the City’s General Plan, and of the draft Gateway Plan, and is supposed to be ready to recommend approval of all three documents to the City Council by July.

After tonight, the commission will have one more meeting in June to discuss the documents and should be making a decision at its meeting on July 11.

After that, Loya said, the commission and the council will schedule multiple joint study sessions during the late summer and early fall, to go over all of the documents together. The Environmental Impact Report should be ready for review by late fall/ early winter and, if everything goes as planned, the city council should be ready to adopt the General Plan and Gateway Area Plan by spring, 2024.

Between now and then, city staff are still taking public feedback on the documents. You can provide feedback by attending tonight’s or other upcoming meetings, or by emailing comdev@cityofarcata.org.

The Arcata Planning Commission meets tonight (Tuesday, June 13) at 5:30 p.m. at Arcata City Hall – 736 F Street. You can view the full agenda and directions on how to participate here.

###

PREVIOUSLY:

- ARCATA’S GATEWAY PLAN: City Releases Draft Plan For Developing Housing in the 138-Acre ‘Gateway Area’ of Town, and Wants Your Input

- Arcata City Council Approves Plan to Convert Valley West Hotels to Homeless Housing, Reviews ‘Gateway Area Plan’ to Create High-Density Housing in Town

- GUEST OPINION: Gateway Plan Does Housing the Right Way

- ARCATA’S GATEWAY PLAN: Planners Propose Converting K and L to One-Way Streets; Transportation and Safety Committee Will Review Plan This Evening

- Confused About Arcata’s Gateway Area Plan? There are Still Opportunities to Learn More and Provide Feedback About How You Want the City to Create More Housing

- Arcata Mayor Atkins-Salazar Can’t Participate in Gateway Plan Work, Says State’s Fair Political Practice Commission in Response to City’s Request for Guidance

- (UPDATE) Arcata’s Mayor Can’t Participate in the City-Defining Gateway Area Plan; These Two Current Candidates for City Council Probably Can’t Either, for the Same Reason

- HUMBOLDT HOLDING UP: Catching Up on the Arcata Gateway Plan With Senior Planner Delo Freitas

- Want to Learn More About Arcata’s Gateway Plan? City Holding Public Meeting on Wednesday to Answer Your Questions

- A Big Week for the Arcata Gateway Area Plan: Planning Commission, Historical Landmarks Committee to Look at the Area’s Past and Future

- A Big Public Meetings on Nordic Aquafarms and Arcata’s Gateway Area Plan Tonight

- ARCATA’S GATEWAY PLAN: Big Meetings Coming! Planning Commission to Consider New Public Engagement Approach Ahead of Big Study Session Later This Month

- TONIGHT at ARCATA CITY COUNCIL: Council to Review Request for ‘Gateway Plan Advisory Committee’, Receive Update on Wastewater Treatment Plant

- ‘Gateway Plan Advisory Committee’; Councilmembers Brett Watson and Alex Stillman Argue Over Stillman Not Recusing Herself From Gateway Meetings

- ARCATA’S GATEWAY AREA PLAN: Arcata City Council and Planning Commission Joint Study Session Tonight; Maximum Building Heights May be Set

- Big Gateway Study Session Produces Few Tangible Results

- What’s Next for Arcata’s Gateway Area Plan? Community Development Director Offers Clarification on Results of Recent Study Session

- TODAY in the GATEWAY PLAN: Arcata Planning Commission Will Discuss Plan’s Potential ‘Community Benefits’ During Special Meeting

- NEXT UP in the GATEWAY AREA PLAN: Arcata Planning Commission to Discuss Building Designs and Bird Safety at Upcoming Study Session

- GATEWAY AREA PLAN: Arcata Will Host Online Public Workshop Thursday Evening to Gather Your Design Input

- GATEWAY AREA PLAN: Fearing that the Community is Growing Restless, Arcata City Council Discusses Ways to Boost Public Engagement

- Arcata Planning Commission Keeps Proposal to Make K and L Into One-Way Streets on the Table, Looks at Other Short-Term Options to Improve K Street

BOOKED

Today: 8 felonies, 3 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Today

CHP REPORTS

No current incidents

ELSEWHERE

RHBB: Two Mountain Lion Cubs Spotted in Fortuna Area

Governor’s Office: Governor Newsom announces appointments 2.11.26

Governor’s Office: Governor Newsom announces permanent closure of AllenCo oil wells, ending years of community harm

Mad River Union: Celebrate creativity, scholarship & storytelling at Cal Poly Humboldt

‘Multiple Individuals’ Fled Into the Woods During Marijuana Enforcement Team’s Search of Illegal Grow Near McClellan Mountain, HCSO Says

LoCO Staff / Tuesday, June 13, 2023 @ 11:40 a.m. / Cannabis , Crime

Outside one multi-story grow house | Images from HCSO

###

Press release from the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office:

On June 7-8, 2023, deputies with the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office Marijuana Enforcement Team (MET) served a search warrant resulting from a month-long investigation into an illegal commercial cannabis cultivation operation in the McClellan Mountain area. Representatives with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, Humboldt County DHHS Environmental Health – HazMat Unit and Humboldt County Code Enforcement assisted in the service of the warrant.

One parcel, located above Little Larabee Creek, was investigated during the service of the warrant. The parcel did not possess the required county permit and state license to cultivate cannabis commercially. Upon deputies’ arrival to the property, multiple individuals fled into the surrounding wooded area.

During the search of the parcel, deputies located 13 large, multi-story grow houses being powered by 14 commercial-size generators. Over 200,000 gallons of diesel, used to power the generators, was found being improperly stored on the parcel in aboveground storage tanks. Nearby these tanks and generators, HazMat investigators documented evidence of fuel spills. Additionally, deputies observed numerous discarded burnt generators and evidence of small wildland fires, including torched trees, in close proximity to these grow houses.

Environmental scientists on scene located four man-made dams which had been placed in the Little Larabee Creek to supply the operation with water.

During the service of the warrant, deputies eradicated approximately 18,511 growing cannabis plants, destroyed over 1,370 pounds of processed cannabis and seized four firearms.

Assisting agencies found the following violations:Additional violations with civil fines are expected to be filed by the assisting agencies.

- Nine water diversion/stream alteration violations (up to $8,000 fine per day, per violation);

- Two water pollution violations (up to $20,000 fine per day, per violation);

- Three depositing trash in or near a waterway violations (up to $20,000 fine per day, per violation);

- Failure to establish a Hazardous Materials Business Plan (HMBP) (up to $5,000 per day, per violation);

- Failure to report a release or threatened release of a hazardous material (up to $5,000 per day, per violation);

- Failure to acquire an EPA ID number (up to $70,000 per day, per violation);

- Failure to prevent a hazardous waste release (up to $70,000 per day, per violation);

- Failure to properly dispose of universal waste batteries (up to $70,000 per day, per violation);

- Failure to make a hazardous waste determination (up to $70,000 per day, per violation);

- Failure to properly label hazardous waste (up to $70,000 per day, per violation);

- Hazardous waste accumulation storage time exceeded (up to $70,000 per day, per violation);

- Failure to close hazardous waste containers (up to $70,000 per day, per violation);

- Disposal of or causing the disposal of hazardous waste at an unauthorized point (up to $70,000 per day, per violation);

- Disposal of used oil by discharge to sewers, drainage systems, surface water or groundwater, watercourses, or marine waters; by incineration or burning as fuel; or by deposit on land (up to $70,000 per day, per violation);

- Failure to prepare a SPCC plan (up to $5,000 per day, per violation);

- Failure to provide secondary containment for aboveground tanks (up to $5,000 per day, per violation);

- Failure to obtain authorization for the storage of more than 1,320 gallons of petroleum.

This case is still under investigation. No arrests were made during the service of the warrant. Upon completion of this investigation, the case will be forwarded to the Humboldt County District Attorney’s Office for review and charging decision.

Anyone with information about this case or related criminal activity is encouraged to call the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office at (707) 445-7251 or the Sheriff’s Office Crime Tip line at (707) 268-2539.

More photos:

stream impoundment

fuel storage with no secondary containment

generators

large fuel storage tank

burnt generator discarded on roadside

Hey Rural-ish Arcatans and McKinleyvillains! Can the Arcata Fire District Interest You in a FREE Address Placard to Help Them Find You In Case of Emergency?

LoCO Staff / Tuesday, June 13, 2023 @ 11:04 a.m. / Emergencies

Press release from the Arcata Fire District:

Do you live in the Arcata Fire District on a rural road and/or down a long driveway? Do you have water access like a private hydrant on your property? If so, please keep reading!

In order for Emergency Services or the Utility Companies to find you, the Arcata Fire District, in partnership with the Arcata Volunteer Firefighters Association, have obtained grants through the California Fire Foundation and Pacific Gas & Electric Company to supply rural residents with FREE, easily identifiable, reflective address signs.

You may have already seen the green address placards along county roads around the District, or signs reading “HELP US FIND YOU.” The Arcata Fire District wants to ensure that as many homes as possible have this type of address sign well displayed and visible.

Also, as necessary, the Fire District may add color accents to signs to indicate a rural water supply or driveways that are long, narrow, or difficult for fire apparatus turn-around. This will assist us in determining the emergency response to those residents and minimize any delays.

Any Arcata Fire District rural area resident needing an address placard can have them supplied and installed at no expense. Fire District representatives will be available to visit with residents or neighborhood groups regarding this program. If you are interested in finding out more, please visit the District’s web page, www.arcatafire.org/rural-address-signs or call the station at (707) 825-2000.

SEA OTTERS! Let’s Bring ‘Em Back! The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is Going to Be Holding a Series of Open House Meetings to This End, Including One in Arcata, Soon

LoCO Staff / Tuesday, June 13, 2023 @ 9:42 a.m. / Wildlife

Hey, y’all! Photo of Alaskan sea otter by Assistant Regional Director-External Affairs, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service — AK/RO/00175, Public Domain. Via Wikimedia.

Press release from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service:

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) will host 16 public open houses with communities in Northern California and Oregon this June to gather input on the potential reintroduction of sea otters to their historical range. The open houses will provide communities and stakeholders an opportunity to ask questions, share perspectives and speak with Service staff about sea otters and next steps in recovery efforts including the potential reintroduction process – should a proposal be developed. The sessions are for listening and understanding concerns — we want to hear from everybody to take the information and consider it, along with the scientific data and information, before determining next steps, if any.

The southern sea otter, one of three subspecies of sea otter, is listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. As directed by Congress, the Service assessed reintroduction feasibility in 2022. The assessment concluded that reintroduction was biologically feasible and may have significant benefits for a variety of species in the marine ecosystem and expedite the recovery of the threatened southern sea otter. The assessment also concluded that additional information about how reintroduction would affect stakeholders and local communities was needed before considering the next steps. There is no active proposal to reintroduce sea otters at this time.

The open houses will help the Service gather further information to inform next steps. As the Service considers the possibility of reintroduction, we recognize that community values and issues are critical in this process. Input from the public and key stakeholders, including ocean users, will be a foundational component in establishing next steps including whether or not a potential reintroduction is proposed, as well as ensuring that proposals, if any are developed, are crafted in a way that benefits stakeholders and local communities.

The Service aims to be inclusive, thoughtful, and scientifically sound as we consider actions to support sea otters, local communities and ecosystem recovery, now and in the future.

Open houses will be held in the following communities in Northern California. A list of locations for both southern OR and northern CA locations is also available in this community flyer.

- Crescent City - June 24, 5:30 PM – 8:00 PM, Del Norte Recreation Department, Gymnasium 1005 H St., Crescent City, CA 95531

- Arcata - June 25, 12:00 PM – 3:00 PM, Cal Poly Humboldt, College Creek Complex, Great Hall Community Center Building, Room 260, 1 Rossow St., Arcata, CA 95521

- Fort Bragg - June 26, 12:00 PM – 3:00 PM, Noyo Center for Marine Science, Discovery Center 338 N Main St., Fort Bragg, CA 95437

- Bodega Bay - June 27, 11:00 AM – 1:30 PM, Bodega Bay Community Center 2255 CA-1, Bodega Bay, CA, 94923

- Point Reyes Station - June 27, 5:00 PM– 7:30 PM, Point Reyes National Seashore, Bear Valley Visitor Center, Red Barn Classroom 75 Bear Valley Rd., Point Reyes Station, CA 94956

- Sausalito - June 28, 10:30 AM – 1:00 PM, Bay Model Visitor Center, Gallery 2100 Bridgeway, Sausalito, CA 94965

- San Francisco - June 28, 5:30 PM – 8:30 PM, San Francisco County Fair Building, Auditorium 1199 9th Ave., San Francisco, CA 94122

- Emeryville - June 29, 11:00 AM – 2:00 PM, Emeryville Senior Center, Main Hall 4321 Salem St., Emeryville, CA 94608

The Service encourages interested stakeholders and publics to drop in any time during the open houses.

Full details and open house information are also available online at this link..

Here’s a Very Important Essay on Native California That You Should Read

Hank Sims / Tuesday, June 13, 2023 @ 7:56 a.m. / Our Culture

From time to time, when we publish news about the renaming of this park or that, we still receive questions — some innocent, some less so — about why that was necessary. We’ve always called it Patrick’s Point! Why do we have to start calling it “Sue-Meg” now? What is “Da’ Yas”? Why should I have to learn to pronounce that?

These questions are a product of the fact that 150 years and change after the fact, we still have not had a reckoning with the genocide and the horror that made that world we live in today, here in California and in Humboldt County in particular. We’ve been willing to shove it to one side for all these years because it was more convenient for us to do so, I suppose.

This leaves us with the innocent and not-so-innocent people asking those sorts of questions. The way to tell the two classes of questioners apart is to see if they actually want answers. And if you’re one of those people who does, I really recommend the reported essay “Reclaiming Native Identity in California” by writer Ed Vulliamy in the June 22 issue of the New York Review of Books. It is the most concise and powerful summary of the history of the genocide waged against the people native to this place that I’ve ever read, and as a bonus it introduces us to some of the people of today who are working to remove the blinders from our history, most of whom are associated with the California Truth and Healing Council. They include Vice-chair Frankie Myers and Judge Abby Abinanti, both of the Yurok Tribe, and Vulliamy spends part of the essay reporting from up here.

Vulliamy starts and ends the essay with those people, and throughout details the things they are hoping to accomplish. But he never strays far from the reasons their work is necessary, and for most of us it’s history that we should have learned in high school but did not:

The genocide of Native Americans was nowhere more methodically savage than in California. Nowhere was there such an explicit intention to “exterminate” — the word is used over and over again in state records — the inhabitants of a land supposedly “discovered.” Meanwhile, a brutal slave market for Indians flourished in California just as slavery was about to be abolished in the South.

As I said, the essay is amazingly concise — it takes about half an hour to read — but there turns out to be plenty of room to back this up. Here’s one particularly sickening passage rooted in a place nearby:

In 1984 James J. Rawls published Indians of California, which made two major contributions. First, Rawls affirmed that “although forced recruitment and Indian peonage were part of life at the missions and ranchos [in Spanish California], the actual buying and selling of California Indians was an American innovation” He compared post–Civil War “Black Codes” with California “Indian Codes” and found that “the parallels between California and the South are particularly striking.”

Rawls detailed how “a common feature of the trade was the seizure of Indian girls and women who were held by their captors as sexual partners.” The Marysville Appeal in December 1851 noted that “while kidnapped Indian children were seized as servants, the young women were made to serve both the ‘purposes of labor and of lust.’” The language is repulsive: Isaac Cox in his Annals of Trinity County (1858) described “the purchase by ‘Kentuck’” of an Indian girl eight or nine years old, “either for his seraglio, to be educated the queen of his heart, or the handmaid of its gentle emanations.”

Unfortunately for us, the essay is behind a paywall. If you’re not a subscriber, I urge you to seek it out. The Humboldt County Library carries the New York Review of Books, and if you have a library card I believe — though I’m not positive — that you can also check out a copy digitally, through the Libby app. It’s sold at Northtown Books. You can buy the current issue for your Kindle or Kindle app for $2.99 on Amazon, or for free if you are a Kindle Unlimited subscriber. (UPDATE: Mitch, in the comments below, says that you can just register on the site and read the article for free.)

You didn’t commit the atrocities that took place here in Humboldt County, or elsewhere in the state or the nation. They weren’t your fault. So there’s no reason you should object to telling the story straight. What would you think of a person who refused to admit to some horrific act of violence he committed on another person, or who refused to atone? Why would you think differently of a society that does that?

Is Housing a Human Right? California Voters Could Decide

Marisa Kendall / Tuesday, June 13, 2023 @ 7:18 a.m. / Sacramento

Photo by Robert So via Pexels

Life, liberty, the pursuit of happiness and…housing?

California lawmakers are trying to enshrine the right to housing in the state’s constitution. But what exactly does that mean in a state that lacks the resources to give everyone a roof over their heads?

Supporters say the constitutional amendment would hold state and local officials more accountable for solving California’s homelessness crisis.

“It’s really a way to make sure elected officials and the government does its job and doesn’t continue to fail so miserably in ensuring access to housing for all,” said the author of Assembly Constitutional Amendment 10, San Francisco Democrat Matt Haney.

But the language of the measure is brief and vague, and doesn’t specify what a right to housing entails or how it would be enforced. Some critics worry the amendment wouldn’t do much. Others fear it would do too much — with unintended consequences.

While several prior attempts to create a right to housing in California failed, this one recently passed its first committee vote. Even if it passes, the proposed amendment would still need approval from California voters.

What would a right to housing do?

The proposed amendment recognizes the fundamental right to “adequate housing” for everyone in California. Local and state lawmakers must work toward fulfilling that right “by all appropriate means.”

That’s about it. What that looks like in practice and how it is enforced would be hammered out by local officials and the courts.

Haney, one of the few state legislators who rents rather than owns a home, called the measure a “game-changer” during a recent rally in front of the Capitol. He was backed by several dozen people carrying signs that read “Housing is a human right” and “Keep families home.”

He said the amendment could influence local planning decisions, such as by empowering lawsuits against zoning rules or policy decisions that restrict affordable housing development. It could also help the state enforce existing pro-housing laws, he said.

According to Michael Tubbs, former mayor of Stockton and now an adviser to Gov. Gavin Newsom, a right to housing also would require the government to regulate landlords, potentially by enacting rent control or tenant anti-harassment policies, or guaranteeing renters a right to counsel during evictions. It also would create an obligation for the government to budget for housing programs, he wrote in a recent op-ed for CalMatters.

Newsom has not endorsed the right to housing amendment.

What would a ‘right to housing’ cost California?

Declaring a right to housing wouldn’t immediately solve California’s homelessness crisis, Haney acknowledged, nor would it require cities to provide housing to everyone or entitle people to free housing.

Decades of under-building have led to soaring housing prices and more people living on the streets. The state needed to build 220,000 new homes per year for two decades to meet its population’s needs, California’s Department of Housing and Community Development estimated in 2000. Last year, the state added just 113,130.

As a result, rents are unaffordable for many Californians. The median rent for a two-bedroom home in San Jose, for example, is $3,100, according to Zillow. It’s the same in Los Angeles.

Ann Owens, a sociology professor at the University of Southern California specializing in social inequality and housing, believes everyone has a right to housing. But she’s not sure how much good putting it in the state’s constitution will do.

“The resources part, I think, is where the right to housing often hits a wall,” she said. “You can have this constitutional amendment, but what happens when you don’t actually have the money to provide it?”

In 2020, Newsom vetoed a bill that would have guaranteed a right to housing, citing its estimated price tag of more than $10 billion a year. An analysis by the Senate Appropriations Committee laid out billions in potential costs for state agencies to design programs and connect people with housing and other services.

Haney’s amendment doesn’t yet have a cost estimate. California would have to spend $8.1 billion a year for the next dozen years to house all its homeless residents, according to a 2022 analysis by the Corporation for Supportive Housing and the California Housing Partnership.

At the same time, several lawmakers expressed concern that a right to housing would go too far.

Assemblymember Joe Patterson, a Granite Bay Republican, voted against the measure in committee last week. He said he’s “really scared” about the leeway California’s judges would have when interpreting a right to housing.

Assemblymember Jesse Gabriel, a Democrat from Woodland Hills and an attorney, worried it would subject every budget decision the Legislature makes to litigation. If legislators allocate money to clean energy or health care, he asked, could someone sue because that money wasn’t being spent on housing?

“The major, major heartburn I’m having right now is around enforcement and implementation of this,” he said, though he ended up voting for the amendment.

Haney dismissed Gabriel’s argument as a “straw man if there ever was one.” But he promised to work with legislators, constitutional experts and housing leaders to address his colleagues’ concerns.

The measure narrowly passed the Assembly’s housing committee and next must clear appropriations.

California renter groups back amendment

If this idea makes it onto the ballot and voters OK it, California would become the first U.S. state to legally recognize a right to housing.

“It would be a really big deal,” said Eric Tars, legal director for the National Homelessness Law Center.

It’s not for lack of trying that it hasn’t been done before. Attempts in 2020 and in 2022 to put the right in the state constitution both failed – neither was heard in committee. And Sacramento Mayor Darrell Steinberg proposed a right to housing in his city, paired with an obligation for unhoused people to accept a bed when it was offered, but it didn’t get far.

The new state proposal likely will meet the same fate, said political consultant Steven Maviglio, who served as spokesman for the campaign against California’s Proposition 21 rent control initiative in 2020. Local officials likely will balk at the cost, he said, as will individual homeowners worried about tax increases.

“I don’t see it having a very long future,” he said.

More than 100 housing and renter advocacy groups and other organizations support the amendment, which is co-sponsored by the Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment Action, ACLU California Action, Abundant Housing LA and several others.

No organizations are on the record opposing the amendment, but the League of California Cities has expressed reservations.

“Cal Cities has concerns with ACA 10, as it does not include the significant investment needed from the state to jumpstart the construction of sorely needed affordable housing throughout California,” Jason Rhine, assistant director of legislative affairs said in an emailed statement.

What’s next?

To make it onto the March 2024 primary ballot, the right to housing amendment must pass the Legislature before it adjourns in mid-September. To hit the November 2024 ballot, it has until June 2024. It needs a two-thirds vote in both houses.

After hearing the feedback from his colleagues Wednesday, Haney said it might take longer than this year to pass his measure.

“I’m not trying to rush this just to force it to the ballot,” he said.

If it does pass, Haney hopes it will help people like Peggy Pleasant, who spoke at the committee hearing on behalf of the amendment. The Los Angeles mother lost her job in 2008 and became homeless, sleeping with her daughter in her car until it was repossessed. She eventually found housing, but recognizes she’s one of the lucky few who did.

“When you’re homeless, you lose housing, whatever, you lose family members,” Pleasant said. “But you lose your hope. And when you lose your hope, that makes you an inadequate person.”

###

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

OBITUARY: Kenneth Dale Ammon, 1953-2023

LoCO Staff / Tuesday, June 13, 2023 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Kenny

began his journey to join his ancestors with passing on May 3, 2023

in Redding. Kenny was born on June 30, 1953 in Hoopa to Wesley Ammon

and DD Martin, when joined his brothers Paul, Jack and Earl. His

parental

grandparents were Chan and Ruth Ammon and maternal grandparents were

Jack and Blanche Hensel. He was an active member of the Tsnungwe

Tribe and was

a resident in Tsnungwe

aboriginal territory

of Burnt Rach/Salyer, California. He graduated from Terra Nova High

School, Pacifica, California in 1970.

Kenny was married to Irene and together they raised four daughters, Tampra, Shane, Jerrie and Lavada.

Kenny was known for his skills as a carpenter. He understood all phases of the profession and was extremely proud that he either built, remodeled and renovated over 500 homes in Hoopa. He would assist family and friends with their building projects by stopping by after his workday to review their progress while pointing out errors, how to correct and lay out the next phase of the project. His memory will be alive forever in the hearts of everyone who knew him. Kenny was a loving father, brother, and husband, but he really shined at being a grandfather.

He is survived by his wife Irene, daughters Tempra, Shane, Jerrie and Lavada and brother Paul Ammon.

He is further survived by nine grandchildren, 13 great-grandchildren and several nephews, nieces, uncles, aunts and cousins.

He was preceded in death by his brothers Jack and Earl, father, mother, step-mother Virginia Ammon and stepfather Lincoln Martin, his grandparents and numerous uncles, aunts and cousins.

Services will be held June 24, 2023 at 11 a.m. at the Ammon Family Cemetery on South Fork Road, Salyer. Followed by a gathering at the home of Tom Ammon, South Fork Road. For those who wish, in lieu of flowers make a donation to the Tsnungwe Scholarship Fund or other charity of your choice in Kenny’s name.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Ken Ammon’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.