This time wasn’t like the others. The mission was the same, picking trash off the ground to prevent it from washing or blowing into the water and further polluting the ocean, but instead of the beach, we scoured a chunk of land along the Eureka side of Humboldt Bay for Coastal Cleanup Day. We knew about the homeless camps along the small wooded spit. Don’t go into the tent areas, don’t pick up clothes or other things that might belong to somebody and watch out for feces. Be respectful. Those were the general guidelines.

Trash on the beach tends to come from one of three main sources: it washes up with the tide, someone dumps household garbage, or people party and leave a mess behind. The beach is, the Surfrider refrain goes, “downstream from everything,” which makes it, in a sense, everyone’s back yard. But as we gathered aluminum cans, plastic bags and food containers on the outskirts of the encampment, the awareness that we’d literally entered someone’s yard unnerved me.

Of course, the area isn’t someone’s yard – it’s public land that would be well served if transformed into usable open space. From there, the bay expands north, south and west, industrial legacy tempered by sandpipers and eelgrass. A few fishermen hung over the pier railing hoping to get lucky. Empty picnic tables stood on an open field perfect for Frisbee or shagging fly balls before Little League playoffs. On a sunny Saturday, the daydream was easy to come by.

But right now, this potential idyll serves as refuge for folks caught in hard times, friends and families who would have to be cleared out if the park were ever to become a community destination. And that phrasing – “cleared out” – as if they, too, were nothing more than something to be swept up and not an integral part of the community fails to reflect my belief that we’re all in this together.

Beliefs are easier as theories, however, and I found today that as much as I advocate against labeling a group of people in a way that makes them “others” – i.e., “the homeless” – my gut reaction was not kumbayah, but worrying about how the homeless would react to us. How would they feel about us being there, near their things, cleaning up the trash they or recent others had left scattered. Would they yell at our volunteers? Our leader had done some early recon, but still, I wondered what the best etiquette was in this situation.

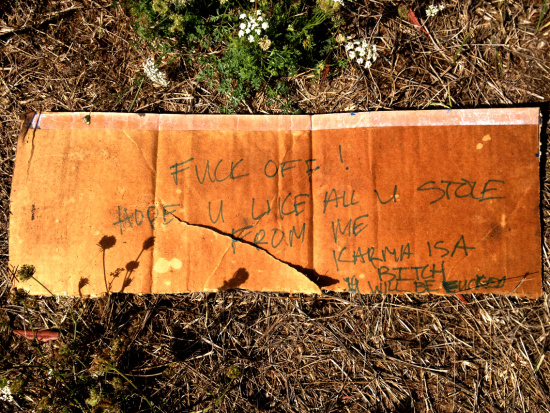

What happened was most of the homeless stayed out of sight and silent. One man complained at us early on. “Some of us pick up trash every day,” he groused. “It’s pretty insulting to have you come down here one day a year and act like you know what’s going on.”

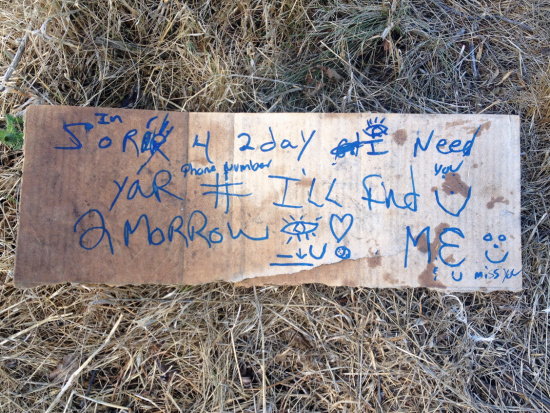

I wanted to thank him for his efforts, but every word choice risked inadvertent condescension. At a loss, I offered him a donut from our snack box instead. He scowled and stomped off. I regretted offending him, aware of my unease at being on “his” turf. A while later, an argument broke out behind the trees. A woman launched into a tirade of accusations, full volume, and didn’t let up as she stormed out and into the parking lot.

Undeterred, our volunteers moved down the path, gloved hands and grabbers gathering cigarette butts, bottle caps, plastic bits. A couple chatted with a woman who’d come out of her tent to let us know the clothes on the bench were there to dry. Her sweet-looking little dog sat politely nearby.

I followed the trail through a thatch of overhead fennel, all licorice on the breeze. Near the end, past the blanket and feces we’d been warned about, piles of abandoned detritus marred the scene. Several trash bags later, our volunteers had returned the patch to a safer state for both human and marine life. Less broken glass for bare feet, less plastics to blow into the bay.

After two hours, we’d removed over a hundred pounds of trash from the overall site. Tangible, immediate good. A tiny step in efforts to solve an enormous problem. Absolutely worthwhile. But as we drove away in our nice dry car toward our sweet warm home, my thoughts returned to the folks left behind.

Around here, we’ve become accustomed to people living on the streets and creating de facto shantytowns in the woods – a reality that sometimes feels inexplicable to me even as I practice it myself. What does that say about us, that we must jettison instinctive compassion to function? Lately, however, frustration with the unstable and dangerous portion of the homeless population has intensified anger toward the dispossessed in general. I worry – these people are so vulnerable already.

But exasperation with the situation is understandable. Safety in public spaces is a legitimate concern – we should be able to enjoy our common outdoor spaces – as are impacts on local businesses, many of which are on fragile ground. People forced to camp illegally are also not typically in a position to follow best environmental practices. Longstanding problems exist not only around the bay, but in the dunes and along the rivers. A group of well-meaning do-gooders showing up once a year to gather other folk’s garbage is something, but it’s no solution.

We need a solution. I hope for one charged with compassion.

CLICK TO MANAGE