Just northwest of Fortuna, the Lower Eel River seems to disappear.

A YouTube video posted yesterday to SFGate.com claimed that the Eel has stopped flowing altogether, which is not strictly accurate. The video above, which was shot this morning, shows that the Eel simply goes underground for a stretch, running beneath the surface of the gravel riverbed before reemerging about 100-200 yards north.

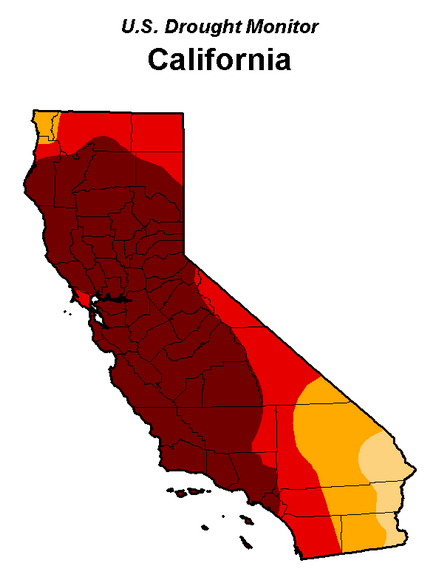

Regardless, this is an alarming and worrisome development for the third-largest watershed in California. We spoke with Scott Greacen, executive director of Friends of the Eel River, about the factors that led to this situation — primarily California’s beyond-extreme drought but also the warm weather and countless illegal water diversions irrigating our county’s illicit marijuana grows — as well as some measures that could be taken to improve things.

“I’m really disturbed,” Greacen said. Low flows in the Eel can be disastrous for fish such as chinook salmon, steelhead trout and especially coho salmon, which need to live in the river a full year before running out to the ocean, according to Greacen. And when flows are low — or go underground — it destroys the breeding grounds for insects that fish rely on. “When you don’t have flow you don’t have food,” Greacen said.

Unlike the Klamath and Trinity rivers, which are impacted by diversions to Central Valley farmers, the Eel River has only local diversions to blame for reducing its natural flow; even PG&E’s Potter Valley Project can’t be blamed, Greacen said.

“It’s important to note that the net effect of Potter Valley Project / Lake Pillsbury releases is to increase the amount of water flowing below Cape Horn Dam in the upper mainstem Eel,” Greacen explained on the Friends of the Eel Facebook page.

It’s the thousands of other diversions — “some of them pretty amazingly large,” Greacen said — in the springs, creeks and rivers that feed the Eel, all those straws stealing bits of flow. “It’s appalling.”

Still, the larger problem is the lack of rain, which has caused “a historically relevant megadrought,” bioclimatologist Park Williams told USA Today.

Still, the larger problem is the lack of rain, which has caused “a historically relevant megadrought,” bioclimatologist Park Williams told USA Today.

It’s not quite at unprecedented levels, though it’s rare — the worst three-year stretch for precipitation in 119 years of records. (Click here for more drought info.) Williams pointed out that “more area in the West has persistently been in drought during the past 15 years than in any other 15-year period since the 1150s and 1160s” — as in 850 years ago.

“The difference now, of course, is the Western USA is home to more than 70 million people who weren’t here for previous megadroughts,” USA Today points out.

According to Greacen, the state needs systemic improvements in water management methods, whether its offering education and incentives for storage and preservation, as the nonprofit Sanctuary Forest has been doing, or developing a system for water rights and enforcement that’s actually effective. “And we don’t have that right now,” Greacen said.

The Associated Press recently explored the flaws in California’s system, finding that thousands of senior rights holders use trillions of gallons of water every day, for free, and with very little oversight. If you care to really dig into our state’s messed up water rights system, check out this study recently produced by researchers the UC Davis Center for Watershed Sciences and the Center for Information Technology Research in the Interest of Society (CITRIS) at UC Merced.

Below is a time-lapse of California water allocations from 1915-2012, using data produced by that study. And remember, Humboldt County’s main agricultural product has no official water rights or documentation of use.

CLICK TO MANAGE