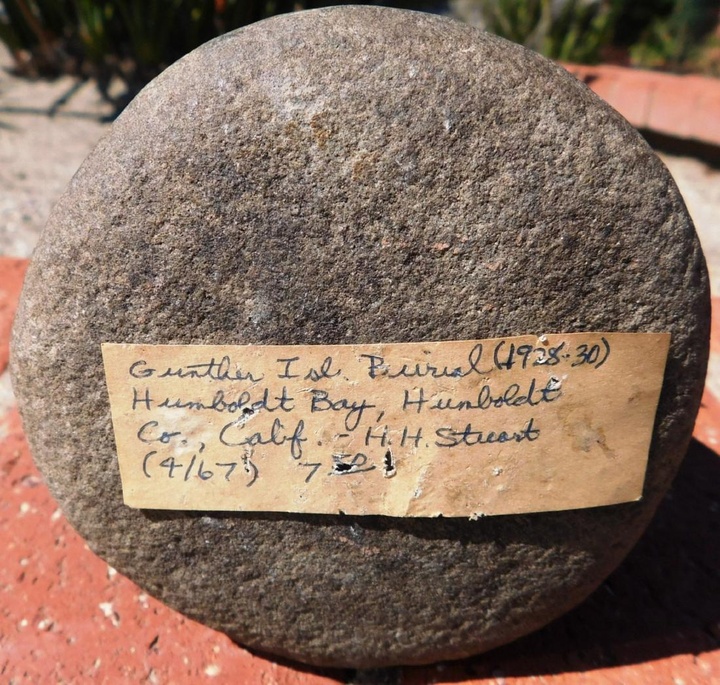

A label on the bottom of this stone pestle reveals that it was taken from a burial site on Gunther Island (now called Indian Island) in Humboldt Bay by Dr. H. H. Stuart. | Image from the Live Auctioneers website.

Another image of the pestle being sold at auction.

Among the thousands of auctions currently being hosted by the popular bidding website LiveAuctioneers.com is one called “A Native American & Tribal Winter.” The particular sale features 239 artifacts including Navajo weavings, arrowheads and ancient stone tools.

One such tool being offer to the highest bidder is the basalt pestle pictured here, an artifact found on Gunther Island (now called Indian Island) in Humboldt Bay sometime between 1928 and 1930. The label on the bottom says as much. The label also includes a name: H. H. Stuart.

That name is familiar to scholars who’ve studied Wiyot and Yurok tribal history. As scholar and author Tony Platt explains in his 2011 book Grave Matters, Eureka dentist H. H. “Doc” Stuart was a “larger-than-life character,” a “bon vivant” who spent years collecting Indian artifacts.

“Stuart was the biggest amateur plunderer in the region,” Platt told the Outpost today via email.

Many of the 10,000 or so Native American artifacts Stuart accumulated during his lifetime he obtained by digging up sacred burial sites of the Wiyot and Yurok tribes. While such practices were common and even sanctioned by universities and museums into the middle of the last century, the tribes themselves have long objected to such grave robbing. To this day they seek the return of such items to the land from which they were stolen.

In “Doc” Stuart’s day, though, he wasn’t viewed as a thief. In 1923 he secured a lease from a private landowner on Gunther Island, which had been abandoned by the Wiyot after the bloody massacre of 1860. Stuart soon got permission to take a shovel to the sacred burial sites there.

“During his extensive excavations on the island, started in 1923, Stuart dug up 382 graves,” Platt writes. There he found not only the human remains of Wiyot tribe members but also tools and artifacts such as the pestle pictured above. Both the Wiyot and Yurok tribes commonly buried such ceremonial items with the deceased to demonstrate that “he or she was someone of distinction here on earth,” Yurok Tribal Elder Walt Lara Sr. is quoted as saying in Grave Matters.

Eureka Books co-owner Scott Brown recently spotted this particular tribal artifact being auctioned off online and posted about it on social media. When the Outpost contacted the Wiyot Tribe, Tribal Chairman and Assistant Cultural Director Ted Hernandez said he was unaware of the sale.

“That’s a nice pestle,” he commented after being sent a link. “I’ll have to look more into this.”

The collector behind “Native American & Tribal Winter” auction is listed as Craig Helm, a southern California collector and broker who, according to his online bio, “always dresses as if he just walked out of a cowboy movie.”

Thanks to a 1990 federal law called the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, tribes can demand the return of items held by a museum or agency that receives federal funding. But since this pestle is part of a private collection, Hernandez and the Wiyot Tribe don’t have any legal recourse to demand its return. All they can do is ask.

“Anything taken from Gunther Island should be brought back to Gunther Island,” Hernandez said. “That way it can be put back with our ancestors.”

Platt said the label on this pestle offers an uncommon level of information. “Often it’s hard to untangle provenance on these items,” he said, “but there’s the proof, with date, site, Stuart’s name, and ‘burial.’ The evidence is clear.”

Helm has sold similar items in the past, including this pestle, which failed to get the minimum bid of $260 before the auction ended last month. And, oddly, he apparently sold the very pestle pictured above during that same auction, getting $340 for it. (The accompanying description, then and now, lists an estimated value for the pestle as $2,000 - $8,000.)

The Outpost reached out to Helm via email but has yet to hear back.

Hernandez said it can be challenging to convince private collectors to return artifacts. “A lot of people are afraid to return them to the tribe because they don’t want to get in trouble for it,” he said. “[But] the tribe is not looking to get anybody in trouble; we just want our [artifacts] to come back home to be with our ancestors.”

The specifics in this case are especially profound. Less than three years ago the Wiyot Tribe held a World Renewal Ceremony on Indian Island to restore some of the cultural identity that was taken by force over the course of many generations. This pestle, which came from that very ground, is symbolic of that history.

“That is a very sacred item for us and a very ceremonial spot for us,” Hernandez said.

# # #

UPDATE:

CLICK TO MANAGE