Image adapted from photo posted to Flickr by JosephLeonardo.

People in Humboldt County die from drug poisoning at more than double the national rate, and they’ve been doing so for more than a decade.

On average, 32 of every 100,000 county residents died from drug poisoning annually from 2002 through 2014, whether through suicide or unintentional overdose.

The national average over that same timeframe was less than 12 per 100,000, though it has been rising rapidly, according to the latest data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The boom in drug deaths has reached epidemic levels, and it’s largely being attributed to increased addiction to heroin and prescription painkillers.

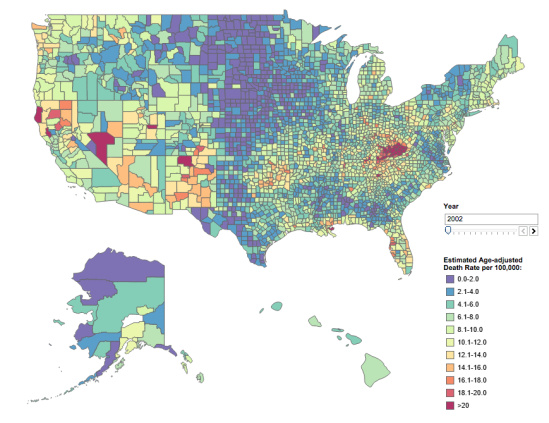

The CDC created an interactive map to help people visualize the spread of this epidemic. It shows every county in the United States, color coded to express the age-adjusted drug poisoning death rates — from lavender for counties with the lowest rate (less than two per 100,000) up through blue, green, yellow, orange and finally red for counties with a rate above 20 per 100,000.

In 2002 the country looked mostly lavender, blue and green:

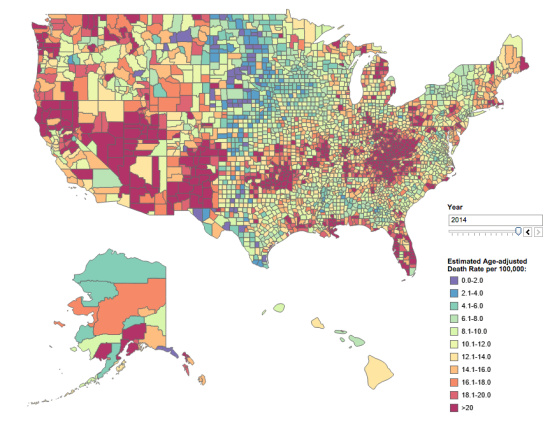

A dozen years later it was overrun with red and orange, and the high rate of deaths cut across urban and rural boundaries:

Eagle-eyed readers will have noticed that Humboldt County was deep in the red from the beginning. In other words, the epidemic that’s causing deep concern and widespread media coverage nationwide has been the status quo in Humboldt for a long time. For perspective, consider this: Five hundred sixty-four Humboldt County residents died from drug poisoning in those dozen years, far outpacing the 329 who died in car crashes.

Methamphetamine use has received the lion’s share of public attention here in recent years, but far more people in Humboldt County are addicted to opioids and opiates, including heroin and prescription drugs such as oxycodone (Percocet, OxyContin), hydrocodone (Vicodin) and hydromorphone (Dilaudid). The most common cause of overdose deaths countywide is multi-drug toxicity, or a combination of whatever substances people can get their hands on.

How bad has the opioid epidemic gotten in Humboldt? Well, the local medical community got a wake-up call about five years ago with a series of reports from various agencies. Dr. Mary Meengs, medical director at the Humboldt Independent Practice Association, remembers seeing one report in particular, from the California Department of Justice’s Controlled Substance Utilization Review and Evaluation System (CURES), which monitors prescriptions throughout the state and breaks down the data by county.

The results, Meengs said, showed that Humboldt County residents were consuming prescription opiods at an alarming rate. The standardized unit of measurement for opioid drugs is “morphine equivalents,” and Humboldt’s daily per capita rate was 72. “That means the average human of all ages [in Humboldt County] was taking 14 Vicodin per day,” Meengs said. And that’s if you account for everyone in the county, including “babies and people in comas,” she explained. So if you subtract the non-users you get an idea how much abuse and addiction we have here.

[Note: The Outpost subsequently learned that the above statistic was false. See here.]

In response to these startling numbers, local health care professionals have embarked on a number of initiatives designed to reduce the deluge of opiods flooding into the community by focusing on increased collaboration, improved education and alternative approaches toward pain management.

One such initiative involves forming an alliance with our neighboring counties in far-northern California — Del Norte, Trinity, Mendocino, Shasta, Siskiyou, Modoc and Lassen — all of which have seen a dramatic rise in overdose deaths.

Before we look at the initiatives underway in the region, it’s worth asking: Why do so many people here OD?

That’s a difficult question to answer, said Michael Goldsby, former director of the Chemical Dependency Treatment Program at Family Recovery Services and an addiction studies instructor at College of the Redwoods since 1987. Goldsby also served as Humboldt County’s alcohol and drug administrator from 1984 to 1988 and recently retired from the Humboldt County Department of Health and Human Services’ Public Health Branch.

“I have never been able to find a single cause for the high rates of drug deaths in Humboldt County,” Goldsby said via email, “except of course for [the] apparent high rates of drug use, abuse and addiction.”

OK, so why do so many people here use drugs? Theories abound, with the most common explanations tending to involve the marijuana industry and its associated culture of permissiveness and experimentation. Goldsby thinks that theory makes sense.

“Risk factors for drug problems include availability of drugs, positive peer attitudes towards drug use [and] community norms that accept drug misuse,” he explained. “Drug and alcohol use is accepted and even encouraged in our community.”

Marijuana plays a role, he believes, even though no one has ever died from overdosing on weed. “[T]he economics and the culture are intertwined and not distinct and separate,” Goldsby said.

Whether or not you buy that theory, the problem is undoubtedly acute, and it has spread across the entire region.

In California, efforts to combat addiction through drug treatment have been undermined in recent years by funding cuts. In 2000 voters overwhelmingly approved Prop. 36, aka the Substance Abuse and Crime Prevention Act, which allowed nonviolent adult drug offenders to choose treatment and supervision instead of jail and/or probation.

The state funded the program to the tune of at least $120 million per year for seven straight years. But funding dropped to $108 million in the 2008/2009 fiscal year, and as California’s budget crisis worsened, money for the program was slashed to $63 million the following year and then zeroed out altogether in 2010. And yet the mandate remains: Anyone who’s eligible can still demand treatment over jail, and it’s up to local jurisdictions to figure out how to pay for it.

In Humboldt, drug treatment funding has been scarce and primarily earmarked for either moms or people involved in the criminal justice system.

“Certainly the need outstrips the resources right now,” said Nancy Starck, legislative and policy manager at the Humboldt County Department of Health and Human Services. On its own, the county lacks the resources to create a system that moves patients through the various stages of drug treatment and recovery.

“Obviously we don’t have a lot of money, and we started to think about how we might do this,” Starck said. Local public health officials started talking to administrators and health directors in other rural northern California counties that are in the same boat. “We thought it may make sense to try to do this regionally, for economies of scale,” Starck explained.

The other eight counties agreed, and together they began negotiating with Partnership HealthPlan of California, the official care provider for all Medi-Cal patients in the region. The goal, Starck said, is to build a more integrated health system “for holistic patient care, so we’re not dealing with separate systems but really looking at substance abuse disorders as the health problem that they are.”

The desired model works like a ladder that includes residential services, withdrawal management, opioid treatment and, critically, reimbursement for case management services to move clients through the system as their needs change. That latter piece has been missing, Starck said, and per state guidelines it requires something called the Drug Medi-Cal Organized Delivery System waiver.

“Providing services under the waiver is voluntary — counties can opt in or out,” Starck said. “So in order to opt in — and we recognize we need these services — the county would need to prove it could provide access to every service in the continuum and figure out how to pay for it.”

That can only be achieved through a regional approach, she said, and the constituent counties are now in the process of analyzing the available financing and trying to figure out how to build the system. The state is willing to entertain a proposal as early as this summer, and in the meantime the eight-county alliance is trying to piece together enough local, state and federal dollars to make it viable.

“There are definitely challenges,” Starck said, “but we really would like to make this work because, boy, are these resources needed in this community.”

Dr. Robert Moore is the chief medical officer for Partnership HealthPlan of California, the nonprofit that contracts with the state to administer Medi-Cal benefits locally, and he said Humboldt County has already shown marked improvement in addressing the opioid epidemic.

“Really, the whole community mobilized,” Moore said. Partnership first came to the county in September of 2013, he said, and through collaborations with local health care providers, particularly Open Door Community Health Centers, the organization has helped to cut back on opioid prescriptions, in part through educating providers on best practices for pain management as well as the use of buprenorphine, a methadone alternative used to treat opioid addiction.

Moore predicts that when the overdose death data comes in for 2015, it will show a sharp decline in opioid-related deaths here in Humboldt County.

“The reason I say that is data show a 50 to 60 percent decrease in [prescription opioid use among] the Medi-Cal population,” he said. He attributes that drop to a lot of different efforts going on separately and simultaneously, and to the community’s dedication to addressing the problem.

Partnership recently held a clinicians forum on improving opioid safety at four of its regional offices — Eureka, Redding, Fairfield and Santa Rosa. And despite being the smallest community in that group by a wide margin, Eureka’s office had the largest attendance.

“That really shows the community is thinking this is an important issue,” Moore said. “The major message is this: Everybody is pulling together to work on this.”

A big piece of that has been the Humboldt Independent Practice Association, which began addressing the issue of opioid addiction about two-and-a-half years ago, spurred by the disturbing data in the Humboldt County’s community health assessment.

“Back in November 2013 we did a call to action to look at the data in the assessment and see if there were strategies the local Humboldt County community could take to affect that alarmingly high death rate,” said Rosemary Denouden, Humboldt IPA’s chief operating officer.

The association has helped to build a collaborative effort that includes local hospitals, the Humboldt County Department of Health and Human Services, the United Indian Health Services, the North Coast Clinics Network, Cloney’s Pharmacy and more.

“We keep adding people to our coalition,” Denouden said. “Recently we’ve added law enforcement and ambulance services. … We just find that no one organization or person will be able to turn this ship. We have to collaborate across our silos and professions and really be intentional in how we address this problem.”

Humboldt IPA formed subcommittees to address various aspects of the problem. One looked at disseminating appropriate prescribing guidelines in hopes of cutting back on excessive use.

“There are lots of stories about someone who had a bad accident, maybe they hurt their back, and got hooked on prescription pain meds,” said Dr. Meengs, Humboldt IPA’s medical director.

Going back to the standard unit of measurement for opioids, most organizations use a cutoff of 120 “morphine equivalents” as the line above which the risk of overdose sharply increases, Meengs said. The conversion rate is different for each drug. With oxycodone (aka OxyContin), for example, the cutoff would be 80 milligrams. Hydrocodone (aka Vicodin or Norco) has a one-to-one conversion rate, so the cutoff is 120 milligrams. Dilaudid, morphine and methadone have higher conversion rates.

“What a lot of people do, they’ll take three 20 mg oxys and then they’ll take six Norcos along with it,” Meengs said. Tolerance for these drugs builds quickly, so people wind up taking more and more to get the same effect. And overdose isn’t the only risk. Chronic use of opioids is bad for the heart, it interferes with sleep cycles, can reduce testosterone production and cause constipation, among other side effects.

Humboldt IPA has worked to spread guidelines that suggest avoiding opioid prescriptions for many short-term acute pain patients and limiting prescriptions for chronic pain to 120 morphine equivalents or less. Doctors and pharmacists can check with the state Department of Justice’s Controlled Substance Utilization Review and Evaluation System (CURES) to make sure patients aren’t being prescribed medications from multiple sources.

The coalition is also working to increase the knowledge and availability of a medication called naloxone, sold under the brand name Narcan, which is used to counter the effects of opioids and can save lives by effectively reversing overdoses. In recent years medical professionals have worked to distribute Narcan not only to emergency responders but also to family members and acquaintances of people at risk of overdosing.

“The goal is to increase greatly the training and distribution of Narcan to increase the number of lives saved, whether by an acquaintance or a first responder,” Meengs said. Some of the highest risk people are addicts who have been discharged from jail. During a long period of non-use while incarcerated, people’s tolerance drops, and so the same dose they took before getting arrested can be fatal following a dry spell.

But it’s not just — or even primarily — street addicts taking opioids. That’s another big aspect of the local health care community’s efforts to address this issue: changing community perceptions. Addicts often get started through genuine attempts to treat chronic pain. “They might be working, they might be on disability, but they’re your neighbors, they’re working right next to you, and they’re at high risk of accidental overdose and death,” Meengs said.

And then there are the people who help themselves to someone else’s supply. “This is how you hear stories about young people having an overdose,” Meengs noted.

Humboldt IPA received a grant in November through the California Health Care Foundation to continue expanding its coalition work. Meengs and Denouden agreed with Dr. Moore’s assessment that prescription opioid use is down in the county.

“We really look for the day when the death data goes down,” Denouden said. “We know many people [addicted to prescription drugs] convert to heroin, but we still have to reduce the amount of prescription opiates that are poured into the community inappropriately.”

With an overdose rate more than double the national average, it may take a while before the local community has enough of an impact to make Humboldt County’s drug poisoning rate acceptable or even average.

“Prevention and treatment are always a good investment, but the payoff is long term, not immediate,” said Goldsby, the addiction studies expert. He supports Humboldt County’s multi-faceted strategy to combat the problem. “Every prevention and treatment approach is valuable. There is not a single approach that will work for everyone.”

Local officials are betting that collaboration across both the county and the larger region will offer the best results with our limited resources.

CLICK TO MANAGE