The murder trial of Gary Lee Bullock is not a whodunnit, argued his defense attorney, Kaleb Cockrum. Nor is it a question of how the crime was committed. The important question, he told the jury, is why.

In delivering his opening statement, Cockrum, who works in Humboldt County’s Conflict Counsel office, went on to suggest that Bullock was mentally unhinged for much of the 48-hour period from New Year’s Eve 2013 through New Year’s Day 2014 — a period during which Bullock allegedly tortured and murdered Father Eric Freed in the rectory of St. Bernard Catholic Parish.

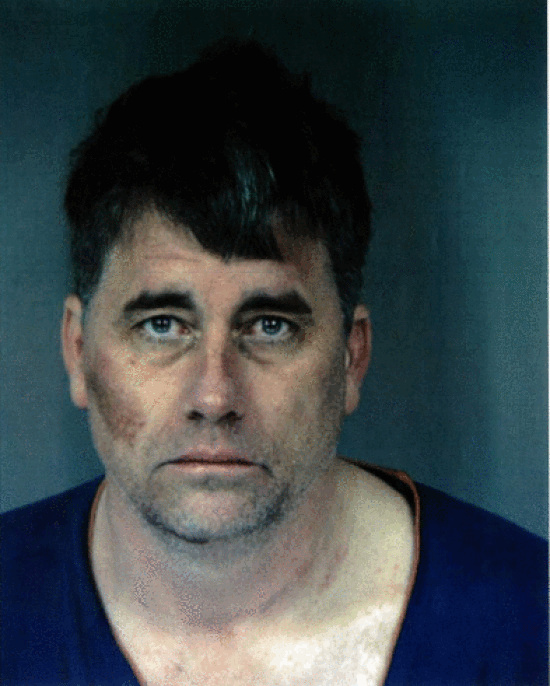

Bullock, age 46, has entered dual pleas of not guilty and not guilty by reason of insanity to seven felonies including murder, torture, attempted arson and carjacking. He sat in the courtroom today wearing a baggy, cream-colored dress shirt as witnesses described his erratic behavior on the days and nights in question.

Cockrum began his opening statement by acknowledging to the jury that the facts of this case inevitably conjure strong emotions such as anger and sadness, and he thanked them for agreeing to set those emotions aside and listen to the facts.

“I will take you through the 48 hours Mr. Bullock had [from New Year’s Eve through New Year’s Day] so you can determine what state of mind he was in,” Cockrum said.

The first defense witness was Kevin McGrath, II, a former neighbor of Bullock’s. From the stand, McGrath recalled being woken around 3 a.m.on New Year’s Eve by the sounds of Bullock and his family arguing — a not-uncommon occurrence — and walking out of his trailer to see Bullock’s then-girlfriend loading up a vehicle to leave with their two daughters and Bullock’s brother.

Bullock seemed “pretty upset” at the time and ran a ways after the car as it drove off, McGrath said.

After the excitement, McGrath went back to bed, he said, and later that morning, around 8 or 9 a.m., Bullock showed up at his sliding glass door “looking un-showered,” wearing socks but no shoes and holding a weed-whacker. Bullock was “frantic,” McGrath said, and he entered the trailer without being invited.

Bullock asked McGrath several times if he knew where his daughters were, and eventually he accused McGrath of kidnapping them and putting them in his freezer, McGrath testified. Bullock then attempted to swing the weed-whacker at McGrath and a struggle ensued. McGrath said he eventually let Bullock search his trailer.

There were rustling sounds inside, though McGrath said was finally able to coax Bullock out of his trailer and they went their separate ways. But McGrath encountered Bullock again less than an hour later, he said. McGrath been down at the river playing his flute to relax, and as he was driving back home Bullock ran across the street and knocked on the vehicle’s window, McGrath testified.

McGrath’s flute was in a case in the passenger seat, and when Bullock saw it he asked if it was a gun. McGrath showed him it was just a flute and Bullock walked back in the direction he’d come from.

Next on the witness stand was Linda Dillon, an employee at Dazey’s Supply in Redway. She said she has known Bullock since he was an adolescent, and when she encountered him outside the store in the late afternoon or early morning of New Year’s Eve he was “walking erratically,” “sweating profusely” and “looking very strange.”

Bullock asked her if she was going to the airport and later, with a contorted face, he asked Dillon if she was his angel,. “I’ve never seen so much sweat [on a person],” she said, adding that Bullock was acting nervous and disoriented.

Another of Bullock’s neighbors, Martin Garza, testified that he, too, got into an altercation with Bullock that morning after Bullock showed up at his house looking for his wife. Bullock actually showed up at the house twice, Garza said, the second time holding a broom.

Cockrum asked Garza if he remembered telling an investigator that Bullock had searched for his wife inside Garza’s microwave. Garza, looking uncomfortable on the stand, said the thought so. He and Bullock got in “a little scuffle” outside Garza’s house, he said, and Garza told him not to come back.

Eventually, Bullock’s behavior drew the attention of law enforcement. Kenneth Swithenbank, a sergeant with the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office, testified that around 1:40 p.m. on New Year’s Eve he responded to the West Coast Mobile Home Park in Redway, where he found Bullock crouched in the bushes in front of space 16. Swithenbank described Bullock as “very agitated, sweating, upset [and] not making much sense.”

Asked what drugs he was taking Bullock said speed and heroin, Swithenbank testified. In his opening statement, Cockrum told the jury that sheriff’s deputies found Bullock “foaming at the mouth” at this scene, but that detail did not come up in Swithenbank’s testimony.

Bullock was arrested for being too intoxicated to care for himself and for being a danger to others. He was detained with little resistance, but after officers drove Bullock to his brother’s house, he began kicking the squad car door from the inside, Swithenbank said.

Swithenbank and a fellow officer pulled Bullock out of the car and further restrained him with a Ripp hobble around his ankles. Bullock was screaming unintelligibly and making “crow sounds,” Swithenbank said.

Bullock was taken from there to the Garberville Sheriff’s substation and then transported 70 miles north to the Humboldt County Jail. Along the way Bullock was intermittently agitated, screaming and hurling himself against the vehicle screen, Swithenbank said. Somehow, despite being handcuffed and hogtied, Bullock managed to get a gold ring off his finger and into his mouth.

This fascinating detail didn’t seem to lead anywhere in today’s testimony.

Between these outbursts, Bullock was quiet for much of the trip, Swithenbank said. “He mentioned I’d saved him and said I was his archangel.”

Bullock’s agitation returned once they arrived at the county jail. He spat in Swithenbank’s face, pulled against his restraints, tried to fight several officers and wouldn’t answer any questions, the deputy testified. Officers put Bullock in a “spit mask” and placed him in a separate room, though eventually they had to take him to St. Joseph Hospital because his blood pressure was too high to admit him to jail, Swithenbank said.

Bullock grew calmer on the way there, though he was still crowing and speaking unintelligibly, according to Swithenbank. After about an hour at the hospital he again grew agitated, and when a female ER doctor walked in to the exam room to take Bullock’s heart rate he lunged at her with his right shoulder, knocking her backwards some distance, Swithenbank said. Still, Bullock was medically cleared to go back to jail.

He was released from jail a few hours later with a brochure about various services in the area and directions to Sempervirens, Eureka’s inpatient mental hospital, Swithenbank said.

In the aftermath of Father Freed’s murder, this action — releasing Bullock from jail after midnight — became the subject of much scrutiny and condemnation. It led to community meetings, a grand jury investigation and eventually a change in policy from the sheriff’s office.

Cockrum today got more specific in his scrutiny of sheriff’s officer actions, asking Swithenbank if he’d talked to Bullock about how he might get back to Redway, or if any jail staff had offered to arrange transportation. Swithenbank said no to both questions.

On cross examination, prosecutor Andrew Isaac asked if deputies ever arrange transportation for released inmates, and Swithenbank said no, they don’t.

Cockrum jumped on that during redirect, reminding Swithenbank about California Penal Code Section 686.5, which requires arresting agencies to provide a ride home to any indigent person who asks for it and who lives more than 25 miles from the place of arrest. (This matter was also examined by the Humboldt County Grand Jury, possibly in connection to the Freed murder, though Bullock was not technically indigent.)

On re-cross, Isaac asked Swithenbank if Bullock had requested a ride home, and the deputy said he had not.

The final witness of the day was Devin Strong, a senior correctional deputy with the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office. Strong was one of the two deputies who escorted Bullock out of jail and onto the streets of Eureka in the dead of night, roughly 45 minutes into 2014.

Bullock had been placed in a sobering cell, and Strong said he checked on him a few times that night before his release. On Bullock’s way out officers handed him his few possessions at the time of his arrest, plus a brochure with information about shelters and drug and alcohol treatment programs.

Bullock was mumbling to himself unintelligibly, Strong said, and when they reached the exterior door of the jail he said something under his breath. Strong asked him to repeat it, and Bullock said, “Can I release you from your prison?” Strong testified.

Strong recalled responding, “No, I’m good.” Bullock was given directions to Sempervirens, and off he went into the darkness. Less than an hour later he showed up on security camera footage at the church rectory, and before dawn Father Freed had been brutally murdered.

On cross examination, Isaac prompted Strong to recall that he’d received crisis intervention training and was thus qualified to notice the signs of someone in mental health crisis. Bullock did not display those signs, Strong said, nor was he acting threatening.

# # #

One interesting side-note to today’s court proceedings: Before jurors and witnesses were allowed into the courtroom this morning, Cockrum and Isaac argued about the status of one potential witness, Eureka Police Detective Jon Luken. It seems the defense has been unable to compel Detective Luken to testify. This despite the fact that Luken has already testified twice for the prosecution in this case — first at a Jan. 21 preliminary hearing and again at a March 1 evidentiary hearing.

Luken is now claiming a medical or psychological reason for being unable to testify again, Cockrum said. So Cockrum asked Judge John Feeney to formally find Luken unavailable and instead allow the admittance of a statement Luken made during a preliminary hearing.

Luken is the EPD officer who responded to the Southern Humboldt property of Bullock’s mother and stepfather, where officers found Freed’s stolen car and the clothes Bullock had worn on the night of the murder.

“We tried to subpoena him,” Cockrum told the judge. The defense team also contacted the Eureka Police Department and was told that Luken is negotiating for worker’s compensation.

“Mr. Luken appears [in court] whenever the People ask him to but not when the defense asks him to,” Cockrum told the judge.

Isaac said he, too, has heard that Luken is now on medical leave — “less physical and more mental” in nature, he said — but he objected to Cockrum’s request to find Luken unavailable, saying Cockrum hasn’t followed all the procedures necessary to allow such a finding.

Judge Feeney agreed, and Cockrum’s motion was denied. It thus remains to be seen whether Luken can be tracked down and compelled to testify.

The case will resume Tuesday at 8:30 a.m.

CLICK TO MANAGE