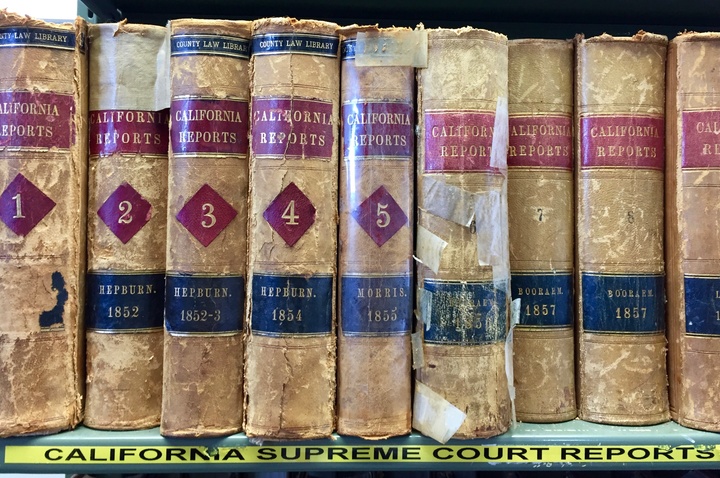

State Supreme Court reports from the earliest days of statehood are among the 10,946 books located at the Humboldt County Public Law Library. | Photos by Ryan Burns.

The Public Law Library of Humboldt County is not an easy place to find. Located on the northwest corner of the county courthouse, it’s only accessible through a pair of glass doors that hide in a shadowy alcove behind a row of parking spots.

But for the people who rely on it, this place is well worth tracking down. With a collection of nearly 11,000 volumes of case law and legal resources, plus computer access to legal databases, the public law library is often the only legal resource available to people who can’t afford attorneys.

Far fewer people visit this library than the public library half a mile away, but the ones who do are typically involved in serious business. Attorneys, paralegals and law clerks research case law while members of the public seek help with everything from child custody proceedings, launching business ventures, fighting evictions and countless other matters decided in our civil and criminal courts.

“If you’ve got your tit in a wringer and you can’t afford a lawyer, the county law library is your only hope,” said Clinton Alley, a former attorney who still uses the library to research legal issues for himself and friends. While computers have made legal research easier, Alley said some resources haven’t been made available electronically, and the personal help from librarians can be invaluable.

Local law library staff made that argument in a recent letter to Governor Jerry Brown requesting more funding for law libraries statewide.

“[People] may enter the library feeling alienated, stressed or even hostile to their government, but the support they find at their County Law Library helps them feel that they too can obtain justice,” the letter states.

While the library’s location may be inconspicuous, it’s also convenient, situated directly beneath the courtrooms of the Humboldt County Superior Court. But for more than a year now the county has been under pressure to relocate the library and relinquish its space to the overburdened court system.

With an unprecedented increase in time-consuming murder cases in recent years, the backlog in our local courts has been accumulating. The retirement of Judge W. Bruce Watson a little over a year ago has only made matters worse. Kim Bartleson, Humboldt County Superior Court’s executive officer, said that even if the Court manages to fill that vacancy — which has proved difficult — it would still need two-and-a-half more judges to handle the caseload. Trouble is, there’s nowhere to put them.

“The court has an immediate need for additional space,” Bartleson told the Outpost. For an upcoming case, she said, the Court is bringing in a visiting judge and holding the trial in a fifth-floor conference room, a desperate measure borne of necessity, though it’s been done before.

Last year, two Humboldt County Superior Court judges — Dale Reinholtsen and Christopher Wilson — were publicly admonished by the California Commission on Judicial Performance for failing to decide cases in a timely fashion, and for submitting false salary affidavits, both symptoms of a “crushing” caseload, according to people who work at the courthouse.

Bartleson said it’s not just courtrooms; the Court also needs space for programs such as its pro tem judges training, which could alleviate some of the pressure on judges by allowing other parties to temporarily serve as adjudicators.

More than a year ago the Court asked the county for more space, and the county is legally obligated to provide that space. The law library occupies 2,160 square feet in the courthouse, and the county wants to give it to the Court.

This idea dates as far back as January 2015, according to Bartleson. That’s before she landed her current position and before Amy Nilsen took the job of Humboldt County’s chief administrative officer.

The earliest documentation of the proposal that the Outpost could track down was from November 2015, when the Judicial Council of California formally requested “that the County agree to relinquish the Law Library space.” In a memo to the county’s then-chief administrative officer, Philip Smith-Hanes, Court Accountant Drew Lund proposed quick action, saying the county and the courts would work together to “effectuate the conversion of the Law Library space to Court Exclusive-Use Area effective January 1, 2016.”

Obviously, that didn’t happen. More than a year later, the law library’s board of trustees remains uncertain about when and where they might be forced to relocate. And the library’s patrons, including many local attorneys, are now up in arms over the prospect of diminished access to the library’s resources.

A library patron eyes the shelves of Supreme Court rulings while making copies.

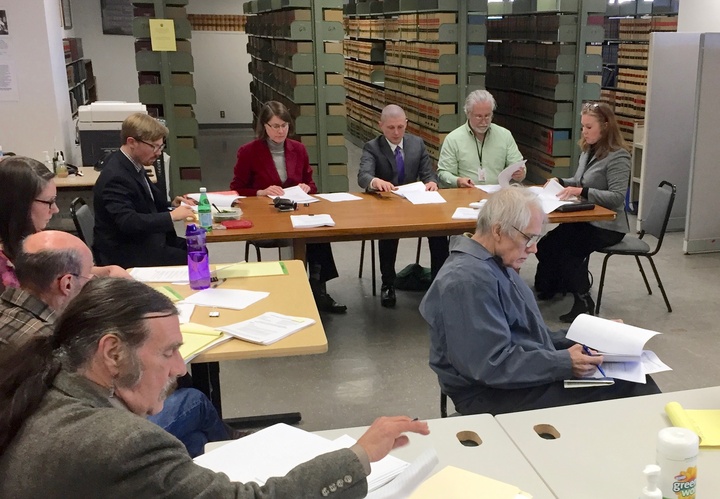

The law library may not be a high-profile part of the Humboldt County government, but its Board of Trustees is comprised of some very prominent names, including District Attorney Maggie Fleming, County Counsel Jeffrey Blanck, Eureka City Attorney Cyndy Day-Wilson and Humboldt County Superior Court judges Marilyn Miles and Timothy Cissna. The seven-person board also includes spots for two attorneys, currently Dustin Owens of Owens & Ross and David Nims of Janssen Malloy, LLP.

The trustees meet once a month, holding meetings at the long tables on the library floor. In the year-plus since being told the library might have to move the trustees have kept that proposal on their agenda as a standing item, hoping each month to get more definitive information. But concrete answers have been hard to come by.

For a time the County was looking to move the law library into the main branch of the public library. Last summer, in an email obtained by the Outpost through a Public Records Act request, Karen Clower with the county CAO’s office urged Bartleson to explain the situation to law library staff.

“It is ultimately the goal that we get the Law Library on-board with the importance of the move, even if it is to the Main Library,” Clower wrote.

That suggestion proved unpopular among law library patrons. Attorneys, paralegals and others wrote to the Board of Supervisors urging them to prevent such a move. Attorney James Flower, for example, noted that he and other “authorized users” have been given keys that allow them access to the law library 24/7.

“People come in before or after court, among the other errands necessary to their lives. Asking them to go across Eureka to the [public] library is unrealistic,” Flower wrote. He said the move would have other repercussions.

“Many times I’ve been in the law library when an unrepresented litigant came in with a question I was glad to be able to answer; I consider it part of my duties,” Flower wrote. “Add the logistic difficulties of an off-site law library and those opportunities will be very scarce.”

Others were more blunt. In December a man named John Stewart told supervisors in an email that moving the law library into the public library was a “horrid idea.”

“Every attorney in this County with whom I have spoken agrees that having the law library in the courthouse is critical to making it usable,” Stewart wrote. “You already have what is probably the most dysfunctional and least user friendly courthouse in the State, and taking away the current law library will only make the situation worse and impede people’s access to the courts.”

“BINGO!” replied former Third District Supervisor Mark Lovelace, endorsing Stewart’s dim estimation of the county courthouse. “Our courthouse is old, ugly, poorly designed and completely inappropriate for the multitude of uses it has to accommodate. However,” Lovelace added, “it is the building we have, and we will all have to live with it until such time as we are able to replace it (don’t hold your breath!).”

While the building is called the “courthouse,” its five floors house a wide array of county divisions including offices for the Sheriff, the treasurer-tax collector, the auditor-controller, human resources and the assessor. The place is fully occupied.

Lovelace explained the situation further: “The courts have been asking for more space for an additional courtroom, and there are not a lot of options for doing so in this horrible building.”

The law library — which, like the Court, is not a county agency — doesn’t pay rent for its space, nor could it afford to do so. Like other county law libraries (every county in California has one) ours receives no general or special fund appropriations from the state. Instead, more than 90 percent of its funding comes via a cut of civil filing fees, ranging from $2 to $50 per case.

Until 2005, counties were allowed to raise filing fees periodically in order to maintain adequate funding to their law libraries. But the Uniform Civil Fee and Schedule Act of 2005 revoked that local authority, giving it over to the state, and in the years since, county law library funding has plummeted. From 2009 to 2015, Humboldt County’s law library saw revenues drop from $125,171 to $89,028, a decline of nearly 30 percent.

The law library’s inability to pay rent has made relocation a challenge. County officials briefly considered moving it to 2956 D Street in Eureka, but an architect said it would cost between $275,000 and $350,000 to bring that building up to code.

More recently the county had its eye on the U.S. Cellular building on the corner of Fourth and I streets. The longtime home of exuberant salesman Corky Cornwell sits catty-corner to the law library. Library staff toured the place in October and reported back to the county that they were “very satisfied that the quarters will be sufficient.”

County staff seemed excited, too, until money was discussed. On October 28 of last year, Nilsen broke the bad news to the law library staff: “The lease to that property is $56,652 per year — too expensive for the county,” she wrote in another email obtained by the Outpost.

The proposed move has proved more challenging than either the Court or the County may have anticipated, in part because the law library patrons, staff and trustees have stood their ground.

The minutes from one Board of Trustees meeting last year hints at tension with county staff:

“CAO Nilsen was under the impression that law library quarters is a ‘gift’ from the county,” the minutes read. “Law library staff informed CAO Nilsen that the provision of ‘sufficient quarters’ is statutory.” Indeed, the state’s Business and Professions Code states that California counties must provide space for law libraries, just as they do for courts.

Another testy item from the minutes noted that Nilsen once claimed “that the law library collection is out of date and no longer being updated. Law library staff corrected the erroneous information and relayed to [Nilsen and Bartleson] that the collection is current and being maintained with up-to-date resources.”

Members of the Public Law Library Board of Trustees (at far table, from left) attorney David S. Nims, DA Maggie Fleming, attorney Dustin Owens, Humboldt County Counsel Jeffrey Blanck and Eureka City Attorney Cyndy Day-Wilson.

Last week, more than a dozen members of the public attended the most recent meeting of the law library’s board of trustees. The board had asked Nilsen and Bartleson to attend as well, so they could explain the current situation. They stood shoulder-to-shoulder along the library’s western wall.

When the agenda item arrived, Bartleson explained that the court still needs the space, especially since the state’s Judicial Council is less likely to send a replacement for retired judge Watson unless there’s a courtroom available.

“We have a need,” Bartleson told the board, “and until I have the ability to get additional space for us we’ll be limited to the judges we have. That’s it in a nutshell.”

But the board wanted more information. Blanck said they’ve been in a “loop for months,” wondering who will make a decision and when. Fleming said the courtroom shortage seemed like an emergency two years ago but lately they’ve heard nothing. And Owens wanted to know how community members can make their voices heard before a decision gets handed down.

During the public comment period, the dozen folks who’d shown up again railed against the idea. Attorney Greg Allen said he’s legally blind and can’t walk due to a fatal heart condition. Relocating the law library would not only cut off access for average citizens of Humboldt County, he said, “but to me personally it is unbelievably discriminatory.”

“There’s no other place to put it,” said another attorney. “There’s no reason to move it. It needs to be where it is.”

One woman suggested moving a county office out of the courthouse instead, something like the assessor’s office, which has nothing to do with the court system.

A man who said he’s been using the law library since the 1980s said it offers crucial support to independent attorneys and “pro se litigants” — those representing themselves.

“My request to you: Stand firm,” he said to the board of trustees. “You have the ability, the necessity, it’s almost a sacred duty, to make sure pro se litigants have access to the library.”

Once the public comment period ended Nilsen responded to some of the questions and comments. Yes, she said, the county wants to relocate some services, like the assessor’s office and tax collector, out of the courthouse, but that project is probably five years down the road. No, she said, the county is no longer considering moving the law library to the public library. “We explored that and there was a lot of resistance, so no,” she said.

But the fact remains that the county is obligated to provide the Court the space it needs, and since that requirement is statutory, relocating the law library won’t require a public hearing.

While law library patrons may consider its current location sacred, Bartleson said the Court’s obligations are also fundamental to justice. “We have a need to have a courtroom so we can get the public’s business done,” she told the Outpost in a phone conversation. And without the additional space, she said, the court is unlikely to get the additional judge it desperately needs.

Furthermore, unlike the law library, a new courtroom has to be located in the courthouse, where security systems and bailiffs are already in place.

Last week’s law library Board of Trustees meeting ended without any definitive answers. Staff from the Court and the law library continue to argue over who deserves the 2,160-square-foot room on the northwest corner of the county courthouse. And both sides argue that their occupation of that space will have a significant impact on justice in Humboldt County.

CLICK TO MANAGE