PREVIOUSLY

- DA Releases Statement on Potential Release of Sexually Violent Predator to the Freshwater Area

- Sheriff Honsal Urges Judge Not to Place Sexually Violent Predator in Freshwater

###

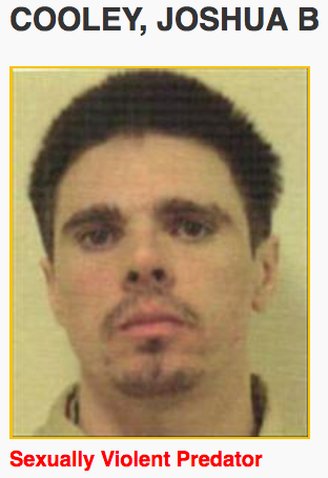

You’d be hard-pressed to find three words that inspire more community fear and outrage than “sexually violent predator.” That’s the designation that’s been given to Joshua Bryan Cooley, a 38-year-old man due to be released after 16 years in prison, and a proposal to place Cooley in the rural community of Freshwater brought dozens of neighbors to the Humboldt County courthouse this morning to voice their vehement opposition.

Image from the California Megan’s Law website.

The overflow crowd inspired Judge John T. Feeney to relocate the community notice hearing from his second-floor courtroom to the more spacious county supervisors’ chambers on the first floor. And still the crowd of roughly 70 people filled the seats of the chamber, with some people forced to stand.

But before anyone had a chance to address the court, Feeney defused much of the collective angst by announcing that he’d reached a tentative decision to deny the proposed placement. Cooley, he said, should be placed in a more urban setting, for the sake of community safety as well as his own.

Even if Feeney hadn’t made that decision — which he did, ultimately — Cooley would not have wound up in Freshwater. The attorney representing him — Meagan O’Connell with the Humboldt County Office of Conflict Counsel — told the court that the issue was moot.

It turns out that the company in charge of finding a placement for Cooley, Liberty Healthcare Corporation, had found marijuana growing in a greenhouse at the proposed property on Howard Heights Road, and the property owner was “unable to comply” with a demand that the plants be removed.

“We would like the opportunity to continue searching for a suitable location,” said Timothy Fletcher, a regional coordinator with Liberty Healthcare.

O’Connell said that search should include the possibility of a “transient” placement, meaning Cooley would stay for limited periods at local motels. The guidelines for placement of sexually violent predators hold that, if at all possible, the offender should be returned to the county where he lived before incarceration. For Cooley, that’s Humboldt.

And so the contentious matter of the day was settled in relatively short order. Community members who’d come armed with speeches, notes and photos no longer had to fight to keep Cooley away. But Judge Feeney invited them to speak anyway, and a handful of people did so. Most argued that a man such as Cooley should never be allowed to reenter society, though one woman said all people should be given a chance at redemption, and Cooley’s grandparents spoke in his defense.

The hearing provided an opportunity for the community and the legal system to wrestle with the question of what to do with a man like Cooley, who has served the terms of his sentence and been cleared for release but who nonetheless has been deemed by some experts who’ve examined him to be dangerous and likely to reoffend.

Cooley was first convicted in 2004 of both sexual battery and lewd or lascivious acts with a child under 14 years of age. (His victim was 12.) He was released in 2006 but violated his probation the following year. Eureka police responded to a noise complaint and found Cooley at a Eureka house party in the company of three minor girls — two 12-year-olds and a 17-year-old — who he’d provided with alcohol and invited into a hot tub.

This was the sixth parole violation for Cooley, who has a history of alcohol abuse and behavioral problems that dates back to his youth. When he was 14 he suffered a traumatic brain injury when he fell 30 feet from a rope swing and landed on his head. He had “borderline intellectual functioning” before the fall; afterwards he grew more aggressive and had trouble with impulse control, according to experts who evaluated him.

One such expert diagnosed him with dementia, caused by the brain injury, as well as alcohol abuse, antisocial personality disorder, and borderline intellectual functioning. California’s Sexually Violent Predator Act, which was signed into law in 1996, defines an SVP as someone who “has been convicted of a sexually violent offense against one or more victims and who has a diagnosed mental disorder that makes the person a danger to the health and safety of others in that it is likely that he or she will engage in sexually violent criminal behavior.”

At today’s hearing, Deputy District Attorney Stacey Eads said that while incarcerated at Coalinga State Hospital, Cooley refused treatment for sexual offenders.

While Feeney’s decision took much of the fury out of the assembled crowd, their concern remained. A Freshwater resident named Tom Cookman said that when another location is identified, “You will have different people here with the same outcry.”

Another, Dr. Richard McCutcheon, said Cooley’s repeated offenses and his refusal to participate in therapy show that he shouldn’t be placed anywhere except an in-patient treatment facility.

Humboldt County Sheriff’s Deputy Scott Hicks read a statement from Sheriff William Honsal, published Wednesday on the Outpost, urging the judge to reject the proposed placement on Howard Heights Road.

A woman named Nicole Riggs said she has a daughter who’s 13 — “his preferred age” — and who participates in the local Teen Court program, which focuses on the concept of restorative justice. Riggs said she believes in that model and in the idea that everyone has the right to lead a good life, and everyone should be given the opportunity to make up for past mistakes.

But Cooley, she said, has expressed no remorse. He has refused treatment and violated his parole. He’s a human being, like everyone in this room, she said, but the focus has to be on the greater good. Medical experts have said he’d be best served by an alcohol treatment program in confined housing. Riggs’s comments earned a round of applause.

Cooley’s grandparents, Shirley and Joseph B. Herrera, approached the microphone together. Shirley Herrera spoke first, softly, telling the room that her grandson was never convicted of rape and that while he’d been designated a sexually violent predator, two of the experts who evaluated him said he did not meet the criteria for that status.

She called the assault that led to Cooley’s 2004 conviction “a big mistake” and said that after spending 16 years locked up, “He’s paid his debt to society, and he want to prove himself.”

Joseph Herrera said being designated a sexually violent predator is “horrible,” but he appreciated the unified response from the community. “We helped raise him … and never saw any violence toward children,” he said. “He’s not really a sexually violent predator, even though he was designated [one],” he added.

And his grandmother said she’s glad Cooley wasn’t placed in Freshwater. The situation has “gotten so scary,” she said, “I would fear for his life.”

Eads, the deputy DA, got up afterwards in part to refute some of what Cooley’s grandparents said. “People have a right to know,” she said. While the criminal code for Cooley’s 2004 conviction didn’t include the word rape, the qualifying offense was indeed “a very violent rape of a 12-year-old girl” in which Cooley’s cousin participated, Eads said. A psychologist who evaluated Cooley in June said he is “in the high range for psychopathy” and is “highly likely to reoffend,” she added.

Given his sexual preference for children and his propensity for sexualized violence, impulsiveness, callousness and dysfunctional coping skills, the People’s position is that placing Cooley anywhere outside Coalinga is dangerous, Eads concluded.

O’Connell pushed back on those statements a bit, saying Cooley has served his time, the court has ordered his release, and a placement — somewhere — is necessary. Cooley, she said, “can’t be held indeterminately. Our laws don’t allow that.” She repeated her request for Liberty Healthcare to continue its search for a suitable location, including the possibility of a transient release.

That’s exactly what Judge Feeney ordered, and he scheduled a review hearing for Oct. 23 at 8:30 a.m. in courtroom three.

CLICK TO MANAGE